JTF (just the facts): A total of 28 black-and-white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space and the side hallway. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 4 toned silver prints, 2013, 2019, 2022, sized roughly 8×8 inches, in editions of 25

- 18 toned silver prints, 1981, 1987, 1990, 1992, 2000, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2013, sized roughly 8×8 inches, in editions of 45

- 5 toned silver prints, 1973, 1983, 1985, sized roughly 6×9, 7×9 inches, in editions of 45

- 1 toned silver print, 1982, sized roughly 9×10 inches, in an edition of 90

Comments/Context: An integral part of the day to day existence of running a site like Collector Daily is the repeated activity of intensely looking at and responding to photography of all kinds. Collectively, our writers visit countless exhibits and shows, watch auctions, read photobooks, and generally look and look and look again, and with nearly every observation, we are subtly making internal judgements and analyses. When we get back to our desks, we are then trying to put that elusive thinking process into words, trying to explain our train of thought, our logic, and our emotional responses to those that are following along.

Today’s review of a show of Michael Kenna’s work comes at this effort from a slightly different angle – in most cases, we are wrestling with the positives of a body of work, trying to articulate why we admire or respect its conceptual or aesthetic features. But in the many years since 2008 when Collector Daily first began, we have failed to engage with Kenna’s work, and at least in my own personal case, this is a result of being quietly skeptical of its charms. While a lack of interest might normally lead me to choose something else to pay attention to (which explains my own previous radio silence on Kenna), when visiting this well-constructed show, I felt the desire to actually reconsider why I generally haven’t resonated with Kenna’s work, and to force myself to confront my persistent resistance.

It’s not like Kenna is in any way lacking in critical support or praise. Across the past six decades, the British photographer has built an enviable photographic career, filled with museum exhibitions, gallery shows, and best-selling photobooks – his consistent publishing partner, Nazraeli Press, with whom he has authored more than a dozen elegant publications, calls him “arguably the most influential landscape photographer of his generation.” After a stint as a printer for Ruth Bernhard in San Francisco in the late 1970s, his early work found him sticking closer to home, in the UK and Europe, and over time, he has become a steady globe trotter, increasingly gravitating east toward Japan and China, where he has found more of a spiritual match for his poetic aesthetics. At this point in his career (he’s now in his early 70s), he has little to prove, and his galleries are looking for new ways to present his prolific career of work, which is what leads us to this smartly edited sampler of his images of bridges.

Kenna is a classic 20th century landscape photographer, in that his subject is essentially always the land itself – mountains, rivers, trees, forests, oceans, hills, lakes, and the like, in all seasons from summer to winter, often in dialogue with the built intrusions and structures of man, from fences and houses to city buildings, and yes, bridges – and his analog black-and-white aesthetics stay largely within the traditional boundaries as drawn by his photographic predecessors. A spin through nearly any Kenna exhibit will elicit compositional echoes of other past masters, a hovering feeling of I’ve seen this kind of thing before, but in an honest, familiar, and reverent way, with homage paid to the way these scenes have been memorably captured previously. Kenna isn’t pretending that those influences don’t exist – quite the contrary, he is leaning in to these historical European, American, and Asian artistic frameworks and adapting them as they relate to his own contemporary picture making.

What separates Kenna’s photographs from the crisper, more descriptive Modernist landscape views we might be recalling from memory is their consistent poetic feeling. I can almost imaging Kenna standing in front of any given landscape around the world and silently asking himself “how can I amplify the spirit of this place?” His aesthetic answer typically involves long exposures, taken either during the day or at night, that massage the available light into moods of mystery and romance. He has playfully explained his work as “‘the decisive 12 hours’, not ‘the decisive moment’”, centering himself on a slowness of looking that patiently waits for the atmospheric essence of the land to reveal itself.

When matched with exquisite attention to detail in the printing process, his results often play with stark contrasts of activated light and dark (or brightness and shadow), and with the elemental patterns that he has found in the landscape and then rearranged into pared down exercises in visual simplicity. His eye brings a sense of well-crafted refinement to these minimalist landscape views, suggesting emotional resonances and near abstractions that are “more like haiku rather than prose.” Again and again across his long career, he has found a precise tone of studied grace, and an enigmatic loveliness that feels like a dramatization of what a landscape might typically make us feel.

Which is, of course, exactly what makes me bristle. Kenna’s sensibility does indeed intentionally heighten the spirit of the natural world, but it also tends to remove its very real frictions. This softening simplification makes his communication a bit more mannered, his vision of the land becoming a kind of embellished performance that has been pared down to evoke a specific response. For most, this makes his pictures extremely easy to understand and to like, but it can also make them predictable or forgettable, somehow looking just like we’d expect them to. I realize this is a minority view, and I continue to try to understand why I think this way, but for me, the stylized perfection of Kenna’s landscapes has emptied many of them of lasting charge, to the point that more than a few seem like exaggerations of poetry rather than authentic poetic searching or feeling. In a sense, when faced with so much intentionally overplayed photographic beauty, but without a unique set of ideas to support that grace, I am immediately placed on my guard.

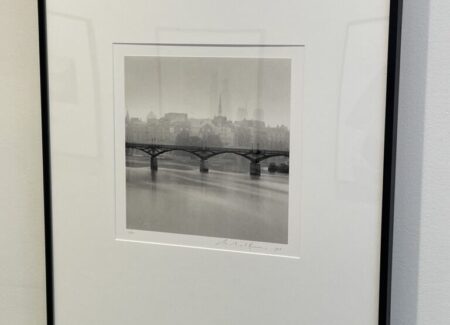

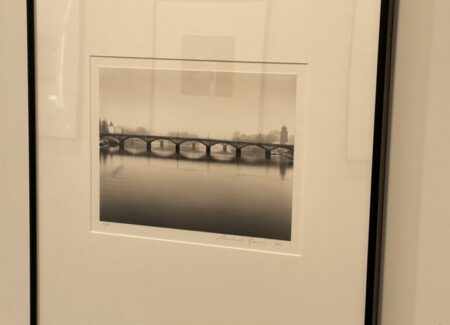

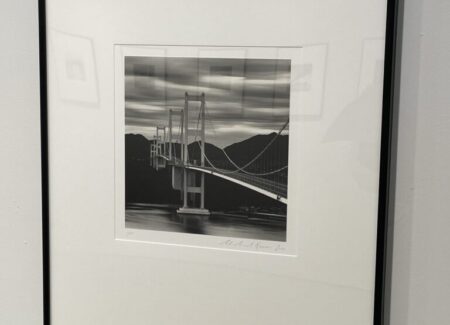

Each of Kenna’s bridge pictures, as seen in this tightly curated show, fits the definition of a grandly aspirational bridge photograph. In examples from around the globe, Kenna offers us variations of tall towers, long spans, sparkling lights, repeated archways, and water-based reflections, even the most recognizable forms (like the Sydney Harbour Bridge, the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, the Brooklyn Bridge in New York, the Pont Neuf in Paris, and the Tower Bridge in London) seemingly seen with their best profiles put forward. Even if Kenna has placed his camera in relatively the same place as other master photographers before him, his pictures build on those visual histories with warmth, acknowledging those views and then remixing them anew.

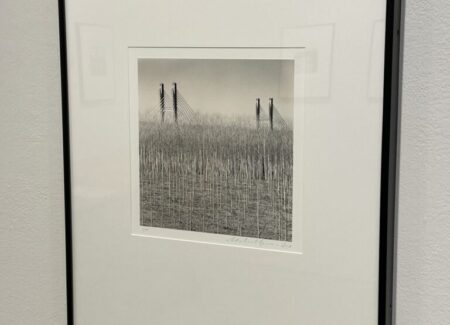

Atmospherics tend to drive many of Kenna’s strongest bridge compositions – the bright lights of New York City beneath the Manhattan Bridge; the misty mountains seen underneath a stone bridge in Anhui, China; the ghostly fog atop the Charles Bridge in Prague; or the nighttime glow off the canal under the Bridge of Sighs in Venice. His image of the railway bridge in Piacenza, Italy, fronted by a stand of spindly trees is wonderfully textural, almost hiding the bridge in a thicket of scratchy lines. His view of the U Bein Bridge in Mandalay shows off his talents for managing contrasts, the repeated wooden struts and their reflections in the water underneath creating an angled march of elegant black geometries. And many other pictures simply use the flatness of the central bridge line as an organizing principle, creating reaching angles, bisected compositions, and low, middle, or high placements that give each bridge its own personality.

Perhaps, in the end, my problem with Kenna’s work is that he makes it look so easy, and that consistently inviting calm is what I am reacting against. What he does photographically (and has done for decades) is nowhere near effortless, and his craftsmanship as a print maker is superlative, and yet I am not moved by his photographs as much as he might hope. Which leaves me with a bit of a perplexed and furrowed brow. Am I too photographically jaded to appreciate an honest artistic attempt at beauty? Or does Kenna’s approach suck the tension out of his views, leaving them pretty but vacant? As they say, your mileage may vary.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced between $2500 and $8000 each. Kenna’s prints are intermittently available in the secondary markets, with recent prices ranging between $1000 and $10000, with most under $5000.