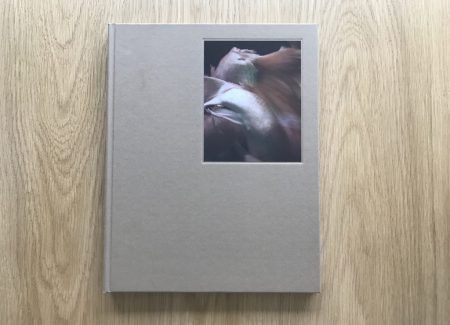

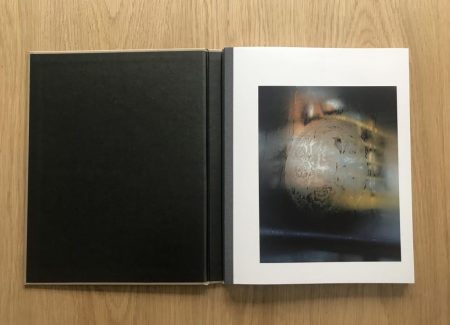

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2019 by Skinnerboox (here). Hardcover, 112 pages, with 72 color images. Includes separate booklet with an essay by Vanessa Hue (in English and Chinese). In an edition of 800 copies. Design by Twelve. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: In our contemporary world increasingly filled with populations on the move, whether they be migrants, refugees, or those fleeing one form of persecution or another, the concept of the diaspora is starting to evolve and expand. Definitionally, diaspora was once a term largely limited to the Jewish population and its exile from its homeland, but its application to Armenians, Africans, and many other groups has grown over time, so much so that the study of how cultures are transplanted and reimagined has broadened significantly.

While Chinese laborers built infrastructure around the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the bulk of the Chinese diaspora generally finds its roots in the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s, when large populations left China to avoid the intense political and social upheaval taking place at that time. Many found homes in the United States and Canada, as well as across southern Asia and Australia, building new lives in their adopted countries.

One of the most complex questions that surrounds diaspora culture is how identity is formed and reinforced for those that have left the home country. Far from their known environment, old traditions and ways of doing things brought along are forced to adapt to new circumstances, and associated attitudes and behaviors slowly change along with them, so the usual pillars of personal identity are constantly under attack. This is especially true for second generation immigrants, who never knew life in the homeland firsthand – they were born in their new countries, and so their identities necessarily fuse old and new. While diaspora culture often has a strong urge or imperative to return home, that process isn’t always as straightforward as it might seem, as the view from afar can become idealized or distorted by both time and distance.

Teresa Eng’s photobook China Dream tries to visually unpack some of these nuanced ideas. Eng’s parents emigrated to Canada from China via Hong Kong (thereby making her a second generation immigrant), and she returned to China between 2013 and 2017 to make the images in this project. As she traveled through China, she struggled to come to grips with what she discovered there, and her photographs document not only a country itself in the midst of major change, but her own frictions in attempting to locate pieces of herself in what she saw around her.

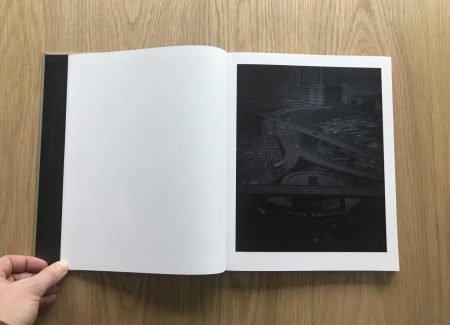

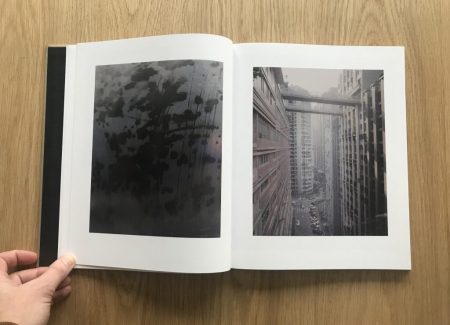

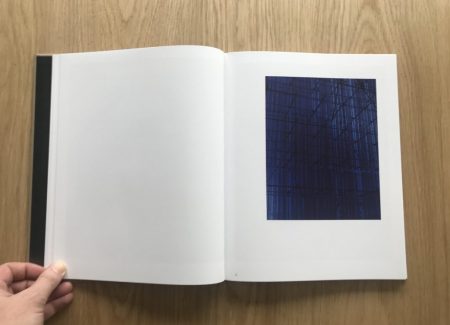

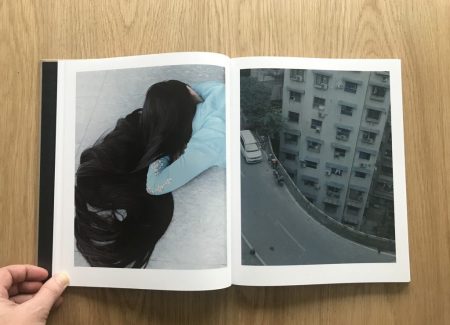

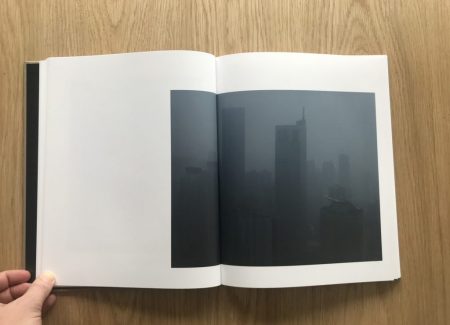

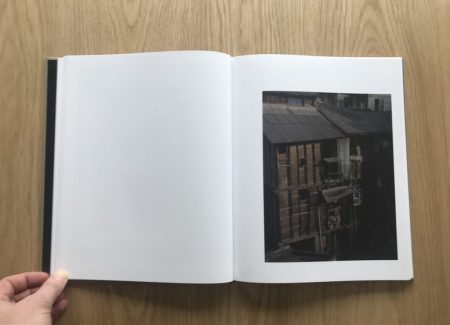

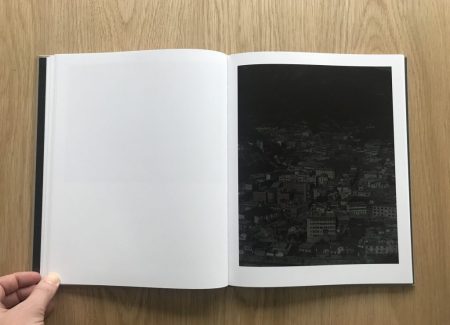

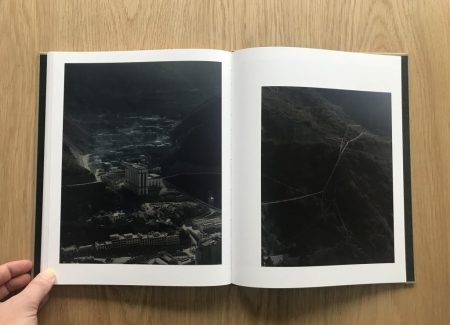

Eng is by no means the first photographer to make images of China’s vast urbanization, the construction cranes that crowd the skylines, the sleek contemporary buildings, or the hulking apartment blocks increasingly packed into tight spaces – this transformation is so thorough and so widespread that it is hard to miss. But Eng’s pictures of these hackneyed subjects are infused with a sense of melancholy. Electric wires stretch and tangle across hillsides, highway overpasses turn and divide, factories hunker along on riverbanks, and whole cities seem to fill valleys like encroaching tides, and Eng mutes them all, toning the light levels and palette down so that the bustle is silenced. Thick enveloping smog makes her city views murky and fogged, the haze further frustrating our ability to see clearly, and faceless concrete housing lingers in underwhelming tones of beige, the punishing scale of its uniformity creating a disheartening mood. Even the futuristic designs and soaring new constructions have a soulless edge, the place for the individual somehow lost in the process of relentlessly chasing newness.

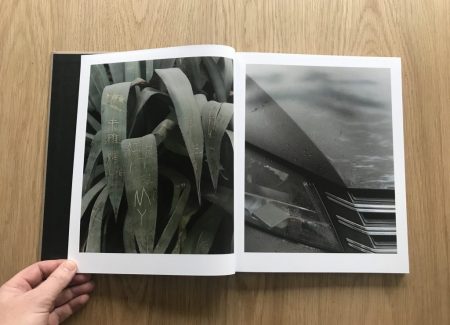

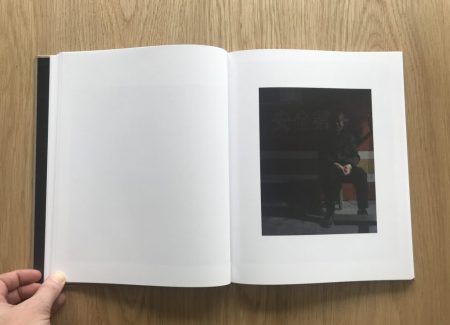

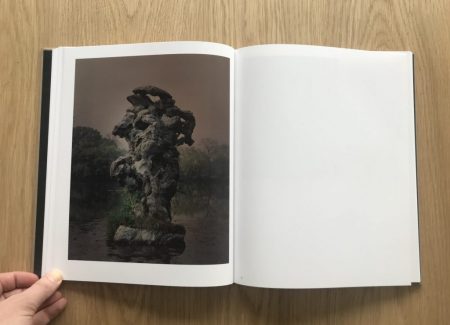

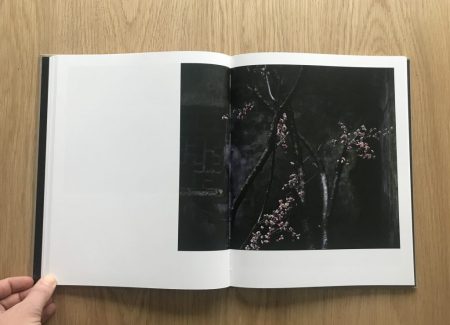

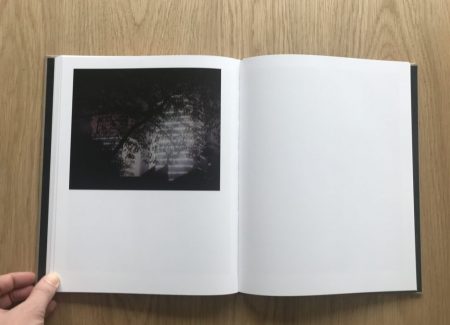

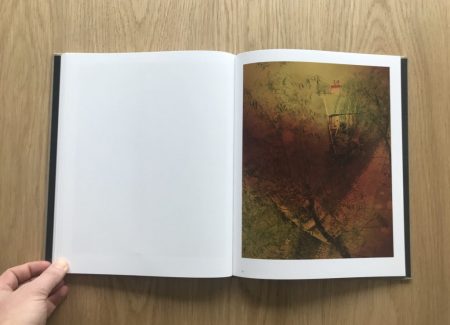

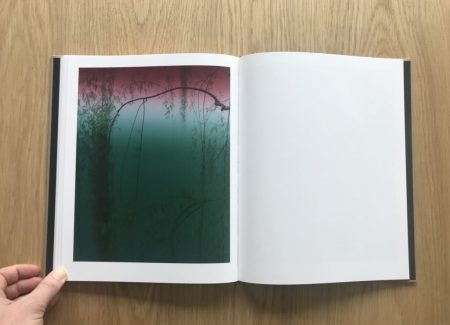

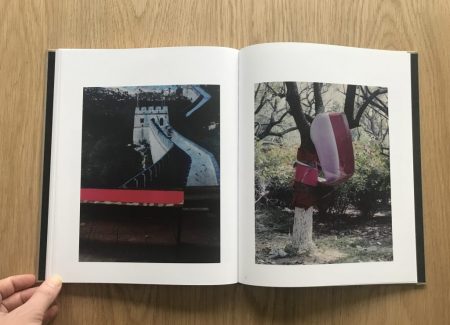

Eng’s quiet alienation and disillusionment push her away from these wide views and toward more intimate subjects. She seems to have gone looking for tangible evidence of the old ways – life on the river, wooden framed houses tucked between steel and glass buildings, shadowy gardens of dense bamboo and ponds covered with lily pads – but found a few too many Great Wall murals and overlit temples. She digs into these symbols, perhaps hoping that they might unlock truths about her heritage or her own path. Many of her images look back to traditions in Chinese art, from arcs of drooping bamboo and the swish of flickering carp in the water to the calligraphic patterns of black spots and the sculptural whorls of eroded rock. And when she sees flowers or trees in bloom, she seems to want to frame them with an eye for elegance and balance, even when they are found in back alleys or trash heaps.

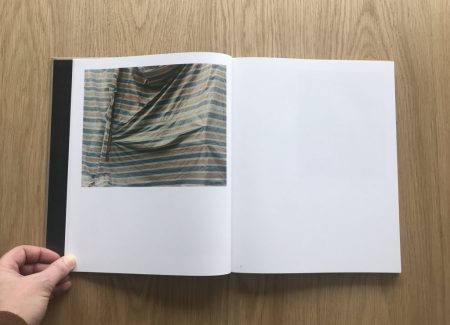

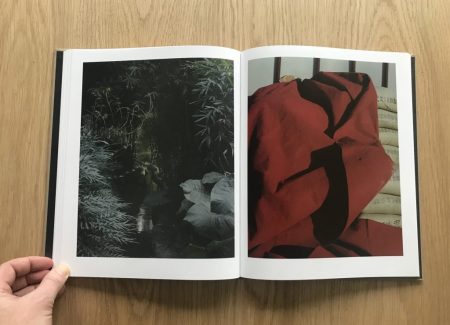

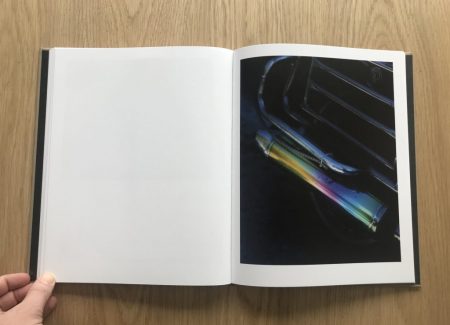

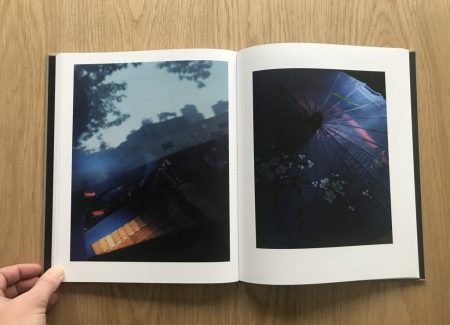

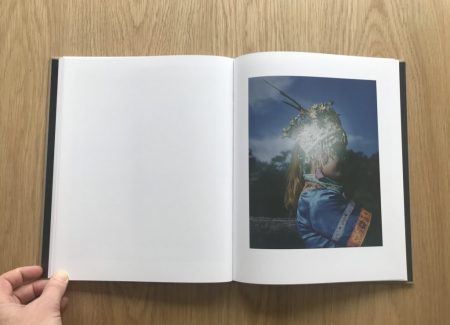

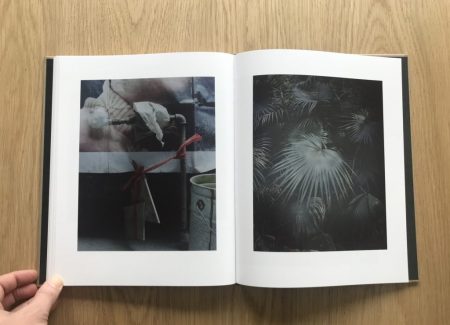

Some of Eng’s strongest compositions are observant studies of detail. She revels in the textures of scraps of fabric, folded tarps, and tumbling drapery, slowing us down to look at each tactile undulation. She catches the shine on fruits wrapped in red plastic, the sweeping wave of a young woman’s black hair, and the improvised functionality of painted tree trunks and wrapped plumbing pipes. And she uses flares of light to find ephemeral beauty in unlikely places, from a rainbowed engine part and a bamboo driving seat cover to a the glow under a painted umbrella and the flash off a traditional headpiece. These pictures remind us that Eng is paying painfully close attention as she visits her homeland, as if searching for clues that might go unnoticed.

In the end, China Dream is a photobook filled with surprisingly tender dislocation. Eng’s journeys (both physical and emotional) seem to have left her with more questions than answers, her mood grasping but never quite connecting, at least in the way she likely envisioned. It documents a powerful sense of being in-between, one foot in and one foot out, both insider and outsider.

Collector’s POV: Teresa Eng does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time, As a result, interested collectors should follow up directly with the artist via her website (linked in the sidebar).