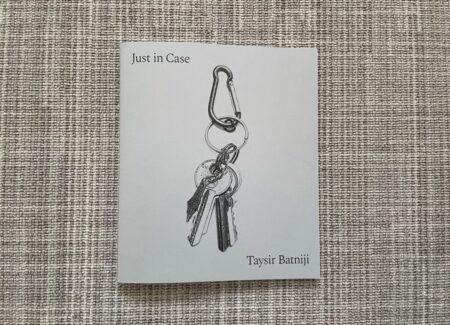

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by Printed Matter (here). Softcover with sewn binding, 8.25 x 9.5 inches, 68 pages, with 55 black-and-white Risograph reproductions. Includes a short introductory text and image captions. In an edition of 300 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

This catalog was produced to accompany an installation of “Just in Case #2” in Printed Matter’s window and gallery space, which ran from October 9 to December 1, 2024 (here).

Proceeds from the sales of this publication will be donated to MECA (Middle East Children’s Alliance), a non-profit organization that works to provide direct aid and community support to children and families in Palestine, Lebanon, and Iraq.

Comments/Context: One of the subjects that photography has a hard time documenting is absence. When things (or people) are missing, removed, invisible, destroyed, deceased, or otherwise gone, there often isn’t something obvious or tangible to put in front of the camera, and so artists must work hard to discover indirect ways to communicate or represent that nonexistence.

War zones are particularly challenging in terms of this documentation of absence problem. Intrepid photojournalists can of course find their way into cities that have bombed, burned, or invaded, only to discover that the fighting is over, the people have long since fled, and all that is left is piles of smoking rubble. And while they can make pictures of what was once a school, a church, a hospital, or an apartment building, what the camera sees is a depressingly familiar jumble of demolished building materials, and sadly, such images of widespread destruction can sometimes fail to tell a compelling visual story, mostly because there is essentially nothing left to see.

If you’ve seen any recent aerial footage from the ongoing war in Gaza, you’ll realize that the near complete destruction of the livable infrastructure of not just individual homes or even city blocks, but entire neighborhoods and cities, has left behind exactly the kind of astonishing conflict-driven annihilation that defies photography. Side-by-side before and after visual comparisons provide the best reminder of what the region once looked like versus its current state, but in the case of this kind of comprehensive obliteration, it’s extremely difficult for photographs of fallen buildings to tell the personal stories of where families once lived and memories were once made. Cityscapes with no identifiable city, or landscapes with no land, leave us only with horrific emptiness.

One of the smartest conceptual solutions to this photographic absence problem I have seen in quite a while comes from the Palestinian artist Taysir Batniji. In the last year, as the Israeli bombardments and ground assaults in Gaza have continued, Batniji has made several hundred straightforward still life images of the key rings of various Palestinians forcibly displaced from their homes. The images (in color) were first installed in a dense grid at the Lyon Biennale this past September (here), and then again here in New York at Printed Matter in October (here). This photobook, titled Just in Case, is a modest monochrome catalog published by Printed Matter in conjunction with that show that pares the original install down into a more manageable edit.

Even without the detailed captions that accompany each picture in the series, we can easily imagine the common human backstory to each of these key rings. While the circumstances and timings may have been somewhat different from family to family, the gut level instinct was likely surprisingly similar – when faced with the imminent destruction of your home and way of life, if you can’t stay to protect these things, you do your best to gather up your family, pack your car (or your backpack, suitcase, wagon, or cart) with whatever you can carry, lock the doors (with a deep feeling of resignation), and drive (or walk) off to wherever you might hope to find safety. For the entire evacuation journey forward, and for however long it takes to get back, the keys in your pocket represent your physical tie to that cherished but imperiled place, and a tangible hold-in-your-hands symbol of the life that you once had.

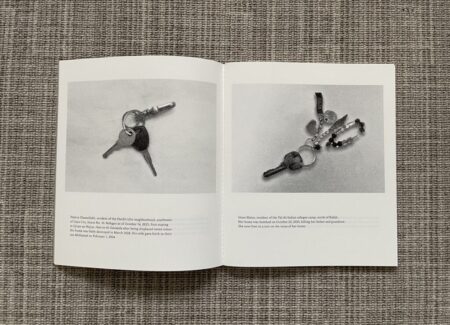

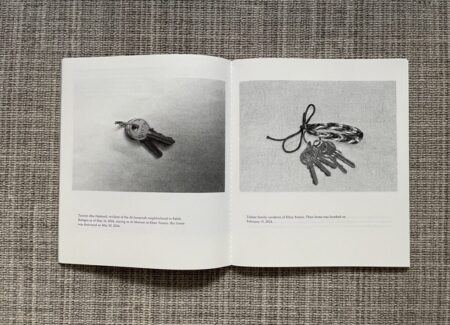

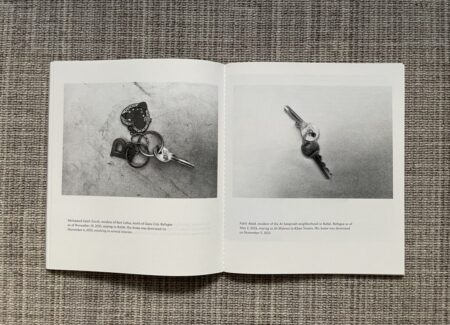

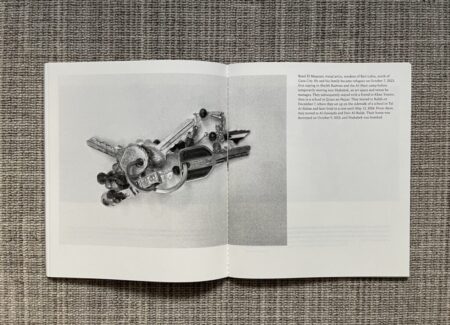

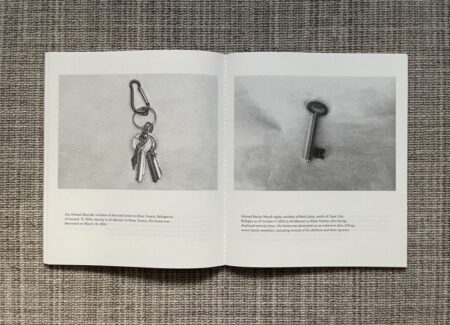

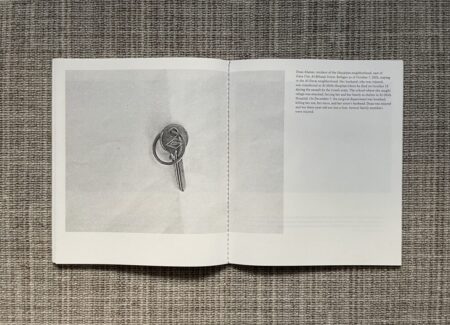

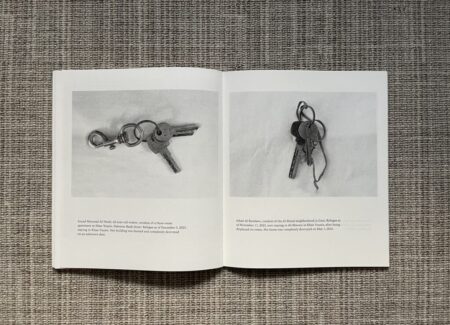

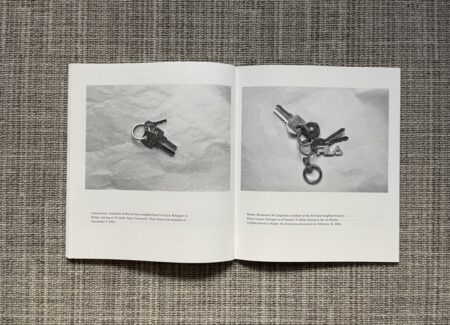

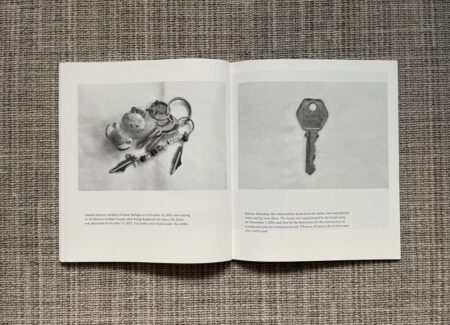

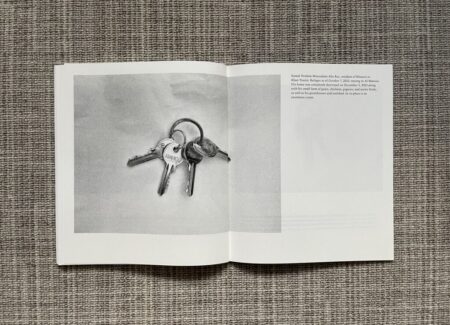

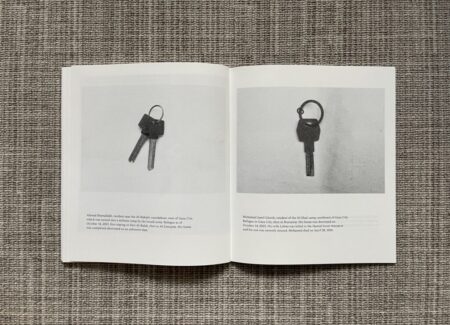

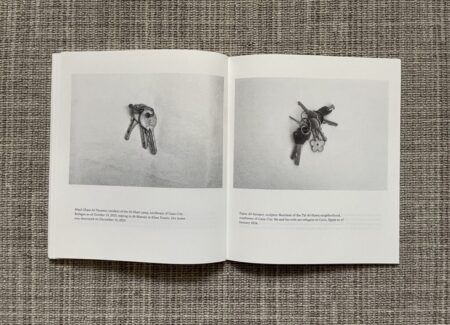

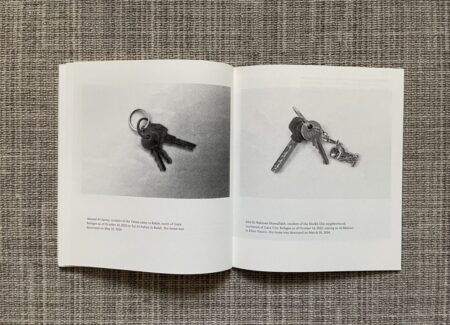

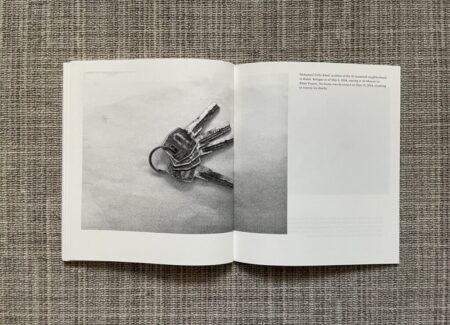

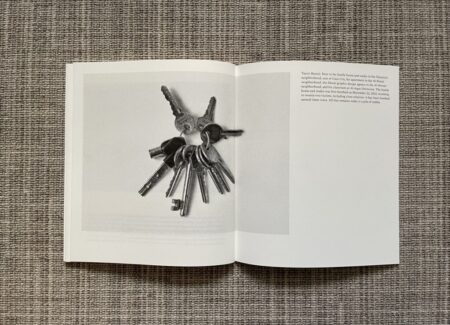

Each of the key ring still lifes in Just in Case places the keys against a blank white backdrop (likely a sheet of paper or tabletop in most cases), with the keys often casually spread out to better see everything attached to the ring. There are no other compositional items, so the forms and shapes of the keys themselves (including a few old style ancient ones) and the other adornments and personal charms attached to the rings come forward. There are single keys and thick bunches, mixed with letters, initials and ID tags, strings of beads, ribbons, clips and fasteners, hearts, Gaza and Palestine symbols, and various souvenirs and branded items, like Hello Kitty and Minion figures. Each ring feels like a quiet personal expression, and a reminder of who the person is and where they come from, ranging from bare bones practicality to more effusive and playful fun.

What makes the images in Just in Case so poignant is of course that there is no going back for these residents, at least in terms of the doors and locks that these keys once opened; in every case included in the project, the home has been burned, bulldozed, exploded, confiscated, or otherwise ruined, destroyed, or abandoned, making the keys functionally useless. And as the captions so grimly recount, for each family, the stories of displacement are consistently and variously tragic. Most of the families have become refugees, staying in various camps, moving from place to place, some as far away as Cairo; a few have tried living in tents; others have been buried under rubble (and pulled out alive) or sought refuge in other places that were subsequently bombed. Far too many of the stories include multiple deaths of family members, with a few key rings belonging to those who have themselves died. Each image caption recounts the facts dispassionately: the person’s name, the location of the home, its current condition, and the place to which they have fled, making the keys something like monuments. The solemn parade of key rings ends with the artist’s own keys to his family home and studio, which were both bombed in November of 2023, resulting in the deaths of twenty-two people, including some of his close relatives. His caption ends with the blunt truth of “all that remains today is a pile of rubble.”

As a photobook object, this catalog is appropriately humble. The images are generally presented two to a spread with captions underneath, with a few single images interspersed that cross the gutter with the caption placed to the right. While there are no essays or texts included, this is undeniably an exercise in image/text pairing, as the captions meaningfully inform the pictures. The paper cover is a muted grey color, with a monochrome image of keys in the center and the artist’s name and title displayed with a minimum of fuss. The overall design and construction reinforce the idea of these photographs functioning as a taxonomy of sorts, encouraging us to see patterns among and differences between the individual examples.

The durable resonance of Batniji’s project comes from the way the keys function as a motif: of home, of homelessness, of loss, of exile/separation, and of personality. For simple domestic objects, they pack a surprisingly complex punch, their very durability as hard metal objects counterbalanced by the obvious fragility (and impermanence) of what they now represent. In a certain way, the residents of Gaza have been forced into a world without keys, which makes the orphaned rings documented in Just in Case all the more mournful.

Collector’s POV: Taysir Batniji is represented by Sfeir-Semler Gallery in Beirut/Hamburg (here) and Galerie Éric Dupont in Paris (here). Batniji’s work in photography has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.