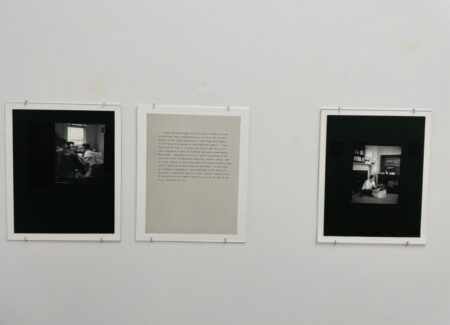

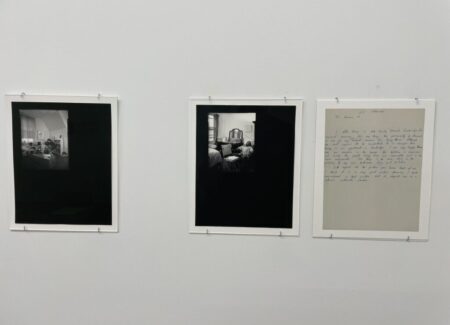

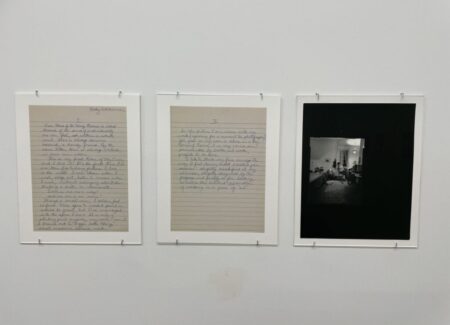

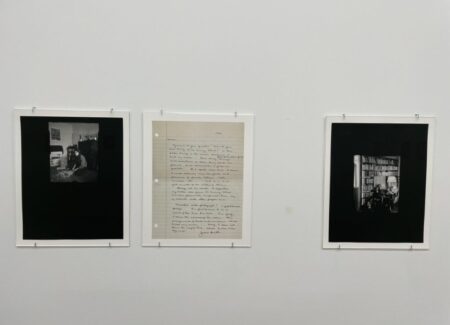

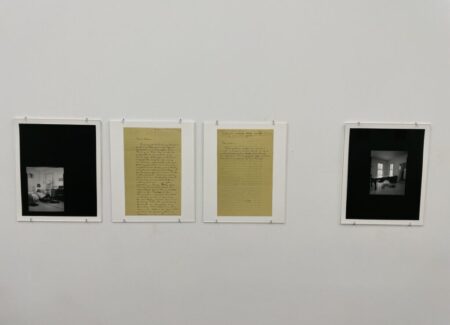

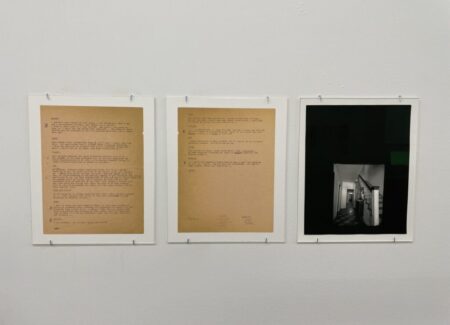

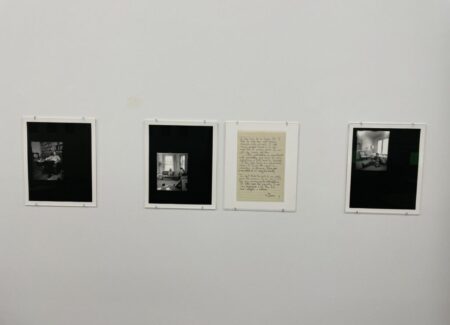

JTF (just the facts): A total of 28 black and white photographs, displayed unframed against white walls in the main gallery space. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 28 gelatin silver prints, 1970-1971, each sized 10×8 inches, in editions of 10

- 22 testimonials/letters

A monograph of this body of work is forthcoming from TBW Books.

Comments/Context: When we think about the many ways that a gallery might use its own exhibitions to support the work of an established artist, the two most obvious are shows of the artist’s brand new work (to the extent it is available or still being made) and sampler shows that gather together notable or well-known images from across the artist’s career. And while these efforts might be the most likely to drive high level awareness and short term sales, those galleries that are playing the longer game of incrementally building and burnishing artist reputations often opt to dig back into the storage boxes to examine particular bodies of historical work in more depth, methodically sketching out the arc of the artist’s development via a richer study of various projects and artistic efforts over time.

In the decade or so since Susan Meiselas joined Higher Pictures, the gallery has applied a systematic approach to the structure of her photographic life, turning back the clock to the 1970s and patiently examining the early projects (both known and unknown) that Meiselas worked on in the first decade of her career. Along the way, the gallery has revisited “Carnival Strippers” from 1972-1975 (in 2022, reviewed here), “Prince Street Girls” from 1976-1979 (in 2017, reviewed here), and “Nicaragua” from 1978-1979 (in 2020, reviewed here), giving each the undivided attention of its own solo presentation.

This show reaches back even further, to 1970-1971, when Meiselas was getting her master’s degree in visual education at Harvard. Given that she was in her early twenties at the time and still very much learning how to best use the medium to tell the stories she wanted to tell, it might be fair to classify this work as juvenilia, thereby giving her some artistic space to take risks, to make inevitable mistakes, and to find her footing with photography. But even in these early pictures, there are glimpses of some of the themes and approaches that would later become Meiselas’s artistic signature, as well as a few standout images that can begin to form a logical starting point for her career, so this trip back in time yields some intriguing discoveries.

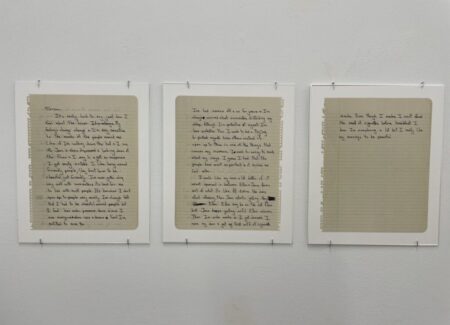

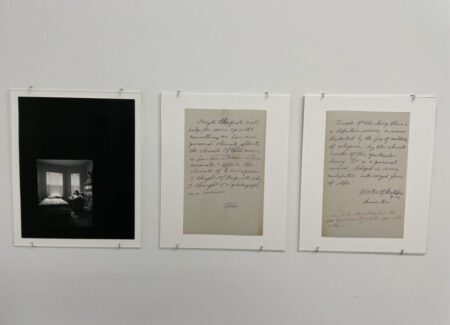

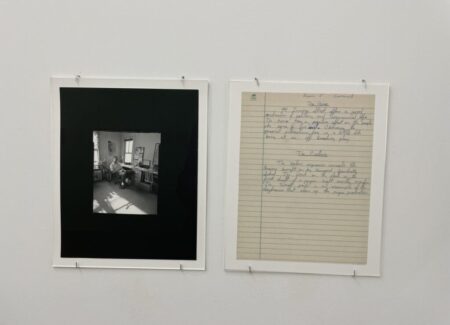

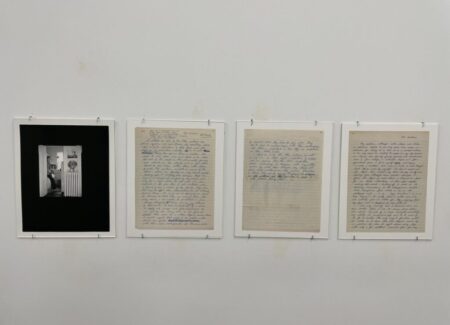

For a project in a photography class at Harvard, Meiselas chose to photograph her neighbors at the boarding house where she was living, at 44 Irving Street in Cambridge. And while there is an endearing naiveté to the idea of a young woman knocking on the doors of relative strangers and asking if she could taker their portraits, this approach of straightforward interest and consistent compassion for her subjects would later become the foundation on which her art was built. Meiselas made her images in her subjects’ rooms, without any additional light, and posed her sitters casually and naturally, as they wanted to be seen. After developing the film and making contact sheets, she returned to share her photographic results with her subjects, encouraging them to reflect on what they saw in her pictures and whether they thought the images captured who they actually were. In this way, each encounter was seen twice – first by Meiselas with her camera, and later, as a written response from the subject – turning it into an unexpectedly balanced and even-handed personal exchange.

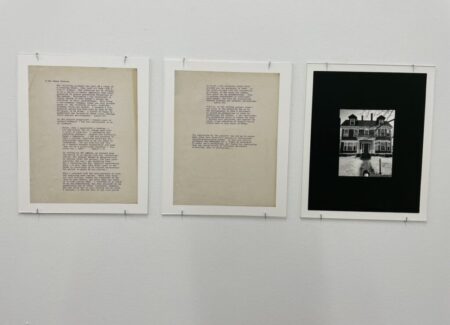

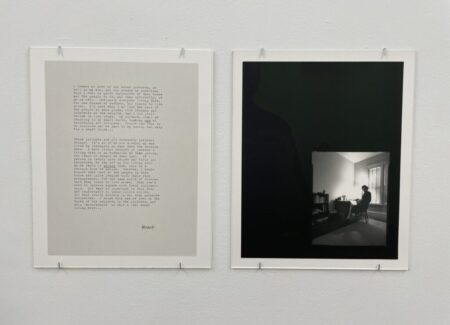

The show is installed as pairings, with each portrait hung with its testimonial letter(s) nearby, so it’s easy to move back and forth between the image and the sitter’s reaction. In terms of image-text interaction, Meiselas’s approach builds on the tradition of extended photojournalistic caption writing and interviewing, but extends it beyond the borders of the photographer’s perspective, intimately bringing the subject’s vantage point into the conversation. While many artists (like Allen Ginsberg, Danny Lyon, and Ed Templeton, among others) have used hand-writing on prints to bring richer and more personal context to their images, very few photographers have encouraged the kind of “in their own words” response Meiselas did here; Laura Aguilar did it later in the 1980s in her series “Latina Lesbians”, where she had her subjects write on their portraits, but the kind of open back-and-forth Meiselas fostered here was, and still is, somewhat unusual.

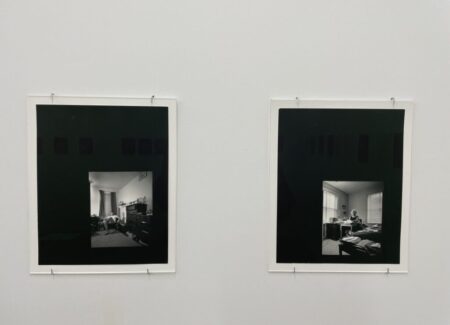

Photographically, Meiselas’s portraits are stepped back and respectful, close enough to see faces, expressions, and body language, but far enough away to allow the context of the furnishings and room to be visible. As we might expect from a boarding house setting in a university town, the rooms are modest and often furnished with little more than a bed and a desk, perhaps with a chair or sofa, a bookshelf, a dresser, and a few personal items scattered about. With blinds or shades on many of the windows, the light is often filtered (even in the brighter morning), creating layers of shadows and darkness that pull us inward toward the featured person. Gesturally, Meiselas notices the small movements that signal unique personalities: standing barefoot in the kitchen, lounging on the bed, sitting with knees pulled up on the couch, talking on the telephone, sitting up straight behind a typewriter, leaning back in a chair, looking over a shoulder while sitting at a desk, and sitting cross legged on the floor. In general, there is work being done and quiet contemplative relaxation taking place, with Meiselas consistently finding moments of introspection or relative calm, where individuals (and a couple or two) seem largely grounded and comfortable, perhaps a bit wary or bemused by the whole process rather than entirely guarded.

But of course, the photographs can only go so far in documenting the inner lives of the subjects, and it is here that the testimonial texts step in to add additional layers of insight and introspection. Asked about how they liked living in the boarding house and whether they thought their portrait accurately captured them, the texts wander in a variety of directions, covering backstories about lives, studies, jobs, relationships, interests, and squabbles with other neighbors, and then dipping into even more personal reflections about identities and tensions seen and unseen by the camera. While the resulting image/text portraits aren’t collaborative exactly, there is a sense that Meiselas has taken the time to get beneath the surface, and this active engagement opened up space for the sitters to reveal themselves more fully.

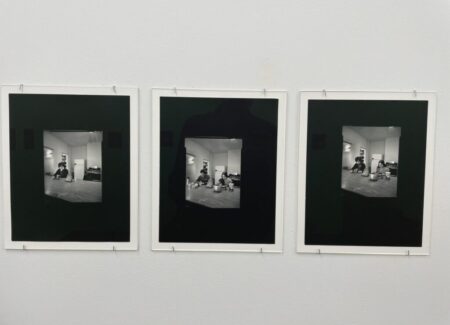

The rest of the images in the show document the spaces of the boarding house – the exterior of the building, the main stairs, the narrow hallways, a shared bathroom on the landing, and the common kitchen. These pictures help set the scene further, providing context for how the residents were living, individually and together. There’s also a ghostly multiple-exposure self-portrait of Meiselas sitting in a chair, turning the camera back on herself, but only providing an elusive hint of her own personality.

While it’s clear that in these early pictures Meiselas hasn’t exactly mastered her craft (a portion of her tripod intrudes into the image of the boarding house from the outside), this unadorned practicality and frankness infuses her photographs with a strong sense of personal authenticity. Her portraits consistently meet the sitters on their own terms, and her genuine interest in their lives and stories is what gives the pictures their durable strength. It is this honest and empathetic connection that would go on to be a hallmark of Meiselas’s work wherever she went, so it’s intriguing to see the roots of that visual vocabulary appear all the way back in her graduate studies.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced at $1500 each. Meiselas’s work has only been intermittently available in the secondary markets in the last decade, with recent single image prices ranging between roughly $1000 and $9000.