JTF (just the facts): Published in 2019 by Photobook Week Aarhus and distributed by Idea Books (here), after being chosen as the winner of Photobook Week Aarhus Dummy Award in 2018. Sewn binding, 144 pages, with color photographs and diagrams. Includes an essay by the artist. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Every photobook, in the very simplest sense, is a reflection of how the mind of the photographer works. On the surface, we generally see subjects, interests, and concerns that are followed, which are then made visible by particular artistic approaches and methods, and each and every one of these is rooted in layers of choices and perspectives. In this way, every photobook can be thought of as a personal example of photographic problem solving, where we watch as a specific mind weighs the options presented by situations, variables, and constraints, and makes countless decisions that ultimately lead to the photographs.

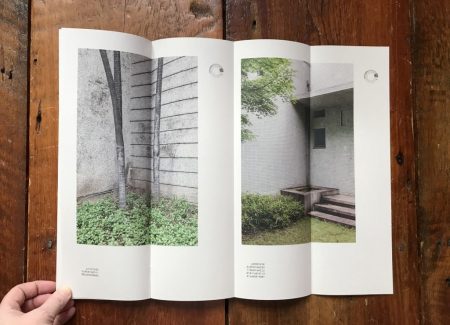

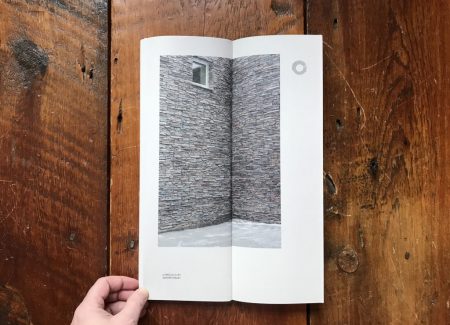

For Stijn Van der Linden, the abstract question that lies at the heart of his recent photobook Essay on the Concave City Corner is how (and when) does a space become a place? While such an inquiry will feel hopelessly esoteric to many, for those interested in urban planning and the development of cities, how a seemingly random or generic space (like a street corner) becomes infused with meaning and value is actually decently mysterious. And so on walks in and around cities between 2010 and 2017, Van der Linden made photographs of the street corners (of the inward variety) he came across, eventually building up a surprisingly deep archive of imagery of this acutely particular architectural form.

That Van der Linden decided to approach his chosen problem by gathering visual evidence, and that he was interested enough in this “problem” in the first place to bother to search for a solution, provide us with some initial clues to his mindset. In other contexts, we might call Van der Linden’s effort scientific, or analytical, or at least systematic – he went out into the world and documented examples of his chosen subject, hoping to discover patterns (or “truths”) that would only be visible after comparing a large number of samples. His brain assumed that employing a methodically structured set of steps could be a path that would lead toward solving his artistic problem.

Van der Linden isn’t, by any means, the first to employ such an approach. Bernd and Hilla Becher are deservedly the standard bearers of such rigor, their systematic photographic documentation of water towers, coal mine tipples, cooling towers, and dozens of other disappearing industrial architectural forms executed with a meticulousness of craft that few have matched since. After making their pictures, they then went further, taking those photographs and arranging them by type, creating the conceptual “typology” that offered the opportunity to make side-by-side (i.e. gridded) visual comparisons.

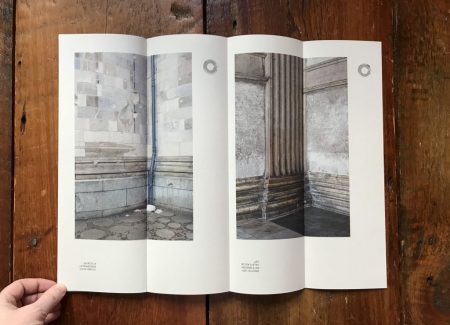

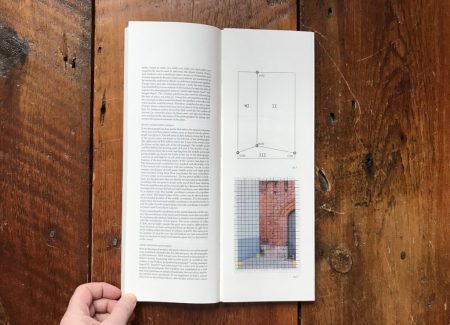

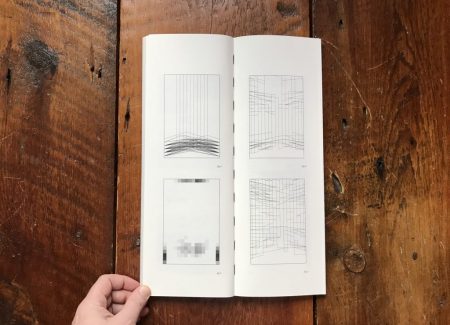

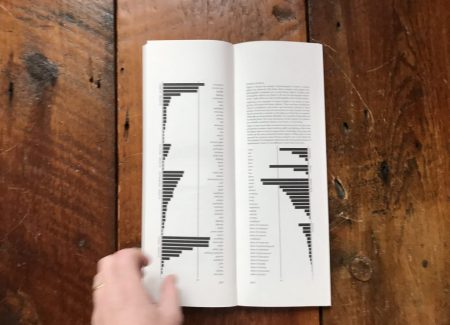

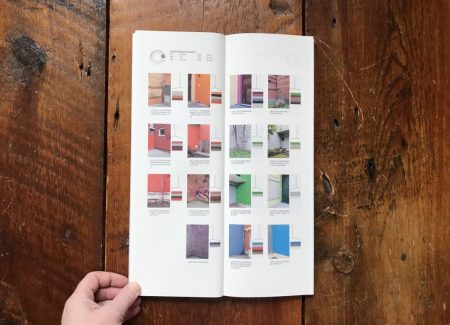

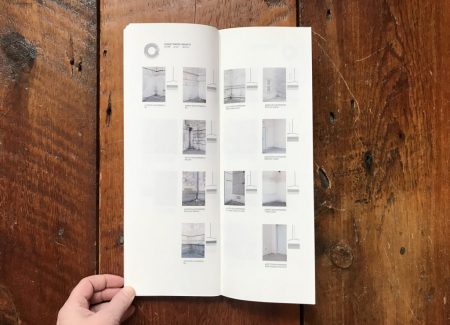

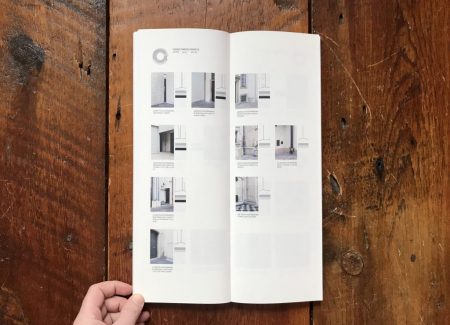

Van der Linden has in many ways taken their example and gone much further, at least analytically. After digitally harmonizing and recropping his images to better standardize them, he embarked on an in-depth analysis of the images, which is patiently, and thoroughly, outlined in his photobook. He carefully identified and categorized the types of places his corners were found in (a place of worship, a place of transport, a place of commerce, a place of education, etc.), the materials used to construct them (stone, metal, wood, plaster, concrete, etc.), and all of the objects observed in the arrangement (further sub-categorized by shape, but including everything from cables and drain pipes to vents, grates, ornaments, and security cameras). He did a spatial analysis of each corner, tracing intersection points, axes, and planes and measuring their locations using a precise coordinate system. He extracted all of the colors in each of the images and did a sophisticated color analysis. And he created an alphanumeric summary code that captures all of these properties in one string.

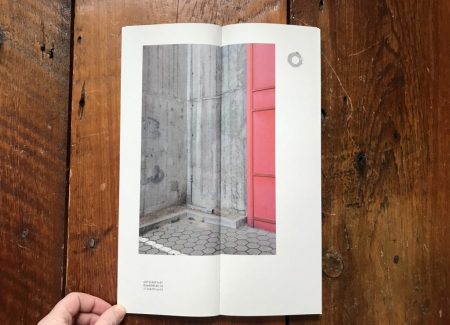

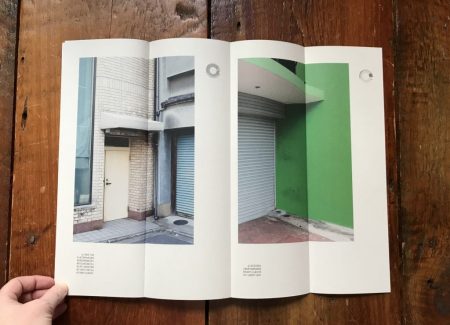

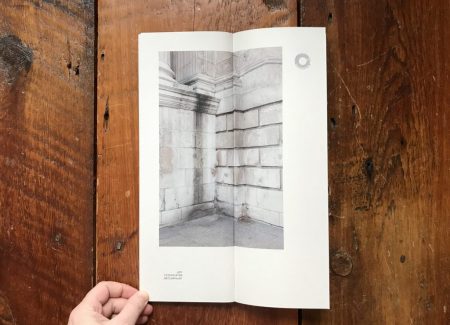

All of this thinking leads Essay on the Concave City Corner to feel like a strangely uneasy hybrid – one part scientific paper and one part art object – and the design of the photobook embraces this dissonance. The book itself is tall and narrow (fittingly just like a corner), and the cover is printed with Van der Linden’s summary codes, which to the uneducated eye, look like computerized gibberish. The first section reproduces the corner photographs one to a spread on light grey paper, each picture accompanied by a radial tree diagram of the color palette; some of the pages are fold outs that put two corner images side by side, creating some visual echoes and pattern matching. These images are followed by Van der Linden’s in-depth analysis, which takes the form of a long essay, with an explanation of his experimental setup, his methods and structures (accompanied by various charts, diagrams, and visual aids), and his conclusions from the data. The last section of the book returns to the images (again on grey paper), this time in thumbnail form, grouped by color family (with line renderings and color stacks for each), once again offering the opportunity to see connections in the subsets.

Regular readers of Collector Daily will certainly have realized that we too have an affinity for structured analysis – one look at the way we organize reviews, process auction data, or categorize our writings will tell even a casual visitor that we like to think about photography with rigor. Which is perhaps why I have found Van der Linden’s failure to answer his own initial question (about how space becomes place) so wonderfully resonant. While he did indeed figure out what the most common concave corner of his city wanderings looks like (no surprise – a place of commerce, with metal, stone, and glass, that is largely grey), this systematized information so hardly won didn’t provide him with actual insight, except to reveal that perhaps people are what make a space a place, since there are no people in his pictures. So what he creates in his photobook is a kind of clever inversion – his whole painstaking exercise eventually turns in on itself, becoming an exaggerated absurdity, almost like a very dry dual celebration/satire of over analysis. What’s pleasantly maddening is that I must acknowledge that I admired both the obsessively structured pictures and thinking, and the twisting reveal that pulls the rug out from under the analysis.

In the end, Essay on the Concave City Corner offers an unexpected dose of artistic self-awareness. Van der Linden seems to be acknowledging both that his mind is drawn to solving problems in certain analytical ways, and that those perceived strengths of approach can become ridiculous when taken to extremes. His smart photobook documents that elusive tipping point, where intense clarity becomes obfuscation.

Collector’s POV: Stijn Van der Linden does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).