JTF (just the facts): A total of 9 photographic works, hung unframed on wooden supports against white walls in the main gallery space. All of the works are unique photographic transfer prints on khadi or khaddar fabric, alternately with zardozi, gota-patti embroidery, beadwork, phulkari silk thread embroidery, and mirror-work, made in 2023, 2024, or 2025. Physical sizes are roughly 25×19, 27×36, 27×37, 33×45, 38×30, 44×33, 50×66, or 63×47 inches, and all of the works are unique. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Embedded in nearly any photographic portrait are a series of contextual questions that can help us understand the nuances of what we’re being shown. Typically, the best place to start is with who the photographer is (which answers the important questions of just exactly who is doing the looking and what his or her perspectives and biases might be), which then quickly leads to who has been chosen to be seen (and perhaps why he or she has been selected). Once these two sides of the visual conversation are established, we can then examine the visual transaction taking place – has the portrait been “taken” or “given”, and what kind of trust and collaboration have been established and taken place between the artist and sitter? If we can evaluate how much influence the sitter had in determining how he or she would be portrayed (from setting and attire to pose and expression), we then have more information to apply to understanding what kind of likeness has ultimately been captured.

In the photographs of Spandita Malik, an Indian artist who studied at Parsons and is now living in New York, and who has often pointed her camera at other Indian women in her homeland, the strong empathetic dynamic between artist and sitter in her work is immediately clear. What makes this woman-to-woman connection even more powerful is the relative imbalance of personal independence and agency possible in their respective lives – most of the women Malik has chosen to photograph not only live in a strongly male-dominated society in India, many have been forced to live their lives in one single room or have been the victims of domestic or gender-based violence. The horrific gang rape cases in India in the past decade, and the general lack of outrage they evoked, were in many ways the trigger for Malik’s passionate interest in the stories of these women, and she soon found herself connecting with various NGOs and non-profits who were supporting women’s rights in various Indian regions, and in particular, those that were teaching women embroidery as a path to financial (and personal) freedom.

Photographically, Malik’s eye is rooted in a straightforward documentary tradition, and her pictures locate her subjects in their own homes, rather than in a formal studio setting. Each of the women was encouraged to choose the spot that she felt most comfortable and at ease, leading for the most part to images set in private bedrooms and outdoor kitchens/patios. Malik then went further in her collaborative approach, allowing the women to select their clothing, their poses, and even whether or not they wanted to look directly at the camera, to look away, or to cover their faces entirely. This is particularly relevant given that the women are survivors of violence – Malik gives them the freedom to craft their own identities, to be seen as they want to be seen (or how they see themselves) rather than in the way someone else (the artist, the viewer, the men in their lives, or society more broadly) might perceive them.

The next step in Malik’s collaborative process involves making transfer prints of the photographs onto decently large pieces of plain fabric, rather than making smaller traditional prints on paper. The choice of materials is both symbolically and practically important – the images have been transferred to locally crafted khadi or khaddar fabrics, the simple hand-spun cloth made famous by Gandhi in his push for self-sufficiency and independence, thereby echoing and supporting similar feelings of resilience and identity in the lives of the women being portrayed in Malik’s portraits. Functionally, the fabric substrate also allows the works to be more easily embroidered, as intricately sewing paper at this scale would likely be an exercise in torn frustration.

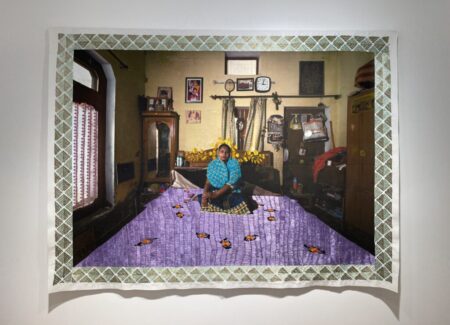

Malik then hands the photographs back to the sitters, who have gone on to painstakingly embroider the unique works themselves. Each work is altogether individual in its design and decoration, with differing regional traditions, motifs, and styles of surface embroidery applied to the underlying portraits. Many of the resulting works feature geometric borders and patterns that frame the images or cover backgrounds (as in “Jamila Bhegam”, “Ranjeet Kaur”, and “Heena”). Others opt for more elaborate floral motifs and swirling vegetation (in “Shabbo”, “Zadaya Bhegam”, and “Shameena Solanki”), with intricate blossoms and leaves surrounding figures or creating natural environments.

The embroidered effects become much more personal when the portrait sitters embellish their own bodies and faces. In some cases, the effects feel optimistically magical, turning modest surroundings into more transcendent settings, like an ordinary plastic chair transformed into a golden throne (again in “Jamila Bhegam”), a bedspread given a regally purple luxuriousness (in “Charanjit”), and a stained wall reimagined as the pages of a book (in “Sameena”). Not surprisingly, many of the women pay close attention to their clothing, giving dresses, saris, and other draped outfits a sense of shine, often with gold or silver highlights. And when they ultimately reach the charged ground of their own faces, a range of careful and deliberate choices have been made, from leaving the images unadorned to covering their faces entirely with thread like masks (in “Pooja”); in once case, halo-like garlands now surround the woman’s head (again in “Charanjit”), while in another, her face has been replaced by a round mirror (again in “Heena”), making it possible to place your own face on her body and more literally inhabit her circumstances.

In the past decade or so, embroidery and other sewn interventions have become increasingly widespread in contemporary photography – and this gallery has held two group shows of such work (here and here), covering a wide range of approaches, techniques, and conceptual frameworks. In some cases, the hand-craftedness of the process has been a counterweight to the prevailing digital photography experience; in others, there has been a more overt feminism present, given that embroidery has traditionally been done by women; and in still others, it has simply been used as an interrupting or decorative tool, breaking up the visual communication of archival images, family photos, and other pictures. Malik’s works touch many of these same ideas, but do so with a profound sense of personal connection – steeped in trauma, the embroidery feels like a step forward in the process of healing and self-determination.

In person, I was surprised by how large many of these works were, by the fluttering lyricism of the hanging fabric (displayed unframed), and by the obvious investment of time and effort required by the sitters to create the embroidered patterns. And even though the underlying photographic portraits are decently uncomplicated, the resulting embroidered works feel altogether more intimate and individual, pulling us into the lives and emotions of the different women. These are works that beg to be seen in person, as opposed to being viewed as thumbnails on the Internet; their physical presence is important, as is the aura of attachment to the subjects. Malik’s collaborative approach doesn’t dilute her own artistic contribution, but instead highlights her sense of compassion and understanding as applied to the lives of her sitters. Her photographic objects are infused with this combined energy, transforming a documentary impulse into something more durably personal.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced between $3000 and $15000 based on size. Malik’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

These are very special, for all the salient points discussed, and the fact they are limited editions of one.

Thank you.