JTF (just the facts): A total of 36 black-and-white and color photographs, variously framed and matted, and hung against white, almond, and black walls in the main gallery spaces and the office area.

The following works are included in the show:

- 34 Fresson prints, 1979, 1980, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1988, 1989, 1991, 1994, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2011, sized roughly 13×17, 16×22, 17×24, 17×25, 24×32, 24×36, 25×36, 28×32 inches, in editions of 15

- 1 archival pigment print, 1984, sized 40×57 inches, (no edition information provided)

- 1 platinum palladium print, 2000, sized 20×27 inches, in an edition of 25

- 1 film (on video screen), 1991

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Sheila Metzner is by no measure the most well known or popular of the fashion and celebrity photographers who came to be associated with the aesthetics of the 1980s, but for those who have an affinity for the unique look of her photographs, Metzner is something of a cult figure. I’ve met many collectors who will wax poetic about their love of Metzner’s prints if given a chance, which always catches me by surprise, as for many others, the mention of her name will likely draw a blank. In the abbreviated parlance of the 21st century, Metzner fits into the category of IYKYK, not so much a shared inside joke, but more a lesser known treasure seemingly appreciated by a select few.

This sampler style survey of Metzner’s work provides a succinct introduction to her signature approach, offering plenty of examples of the kinds of prints that have kept people raving. The show appropriately centers on her editorial work from the 1980s and 1990s, and then sprinkles in examples from the fine art side of her career, largely in the form of nudes, still lifes, and florals made during that same period, essentially leaving out much of what she has made in the past decade or two. If you’ve never seen a Sheila Metzner photograph before, this is a fine place to start, and if you’re already a Metzner supporter, there are plenty of gems here to reinforce that opinion.

As you enter the gallery, the first two pictures on the right offer a perfect way to get oriented. One is a single isolated orchid blossom set against an empty backdrop (from 1999), and the other is a woman seen in profile, wearing a red jumpsuit and with a rather severe 1980s haircut (from 1980). In terms of subject matter, it isn’t at all impossible to see an initial echo of the work of Robert Mapplethorpe in these photographs; his photographs are far more famous than Metzner’s, and he made many images of these kinds of subjects, with a particular brand of simplicity and precision that seemed to intensify even the most elemental forms. But then you look at the rich, almost mottled lushness of these prints and Mapplethorpe vanishes from your brain – these are something else entirely, filled with a kind of tactile romanticism that is almost puzzling, if only because it is so grandly unexpected.

It is at this moment that we need to take a short detour into photographic process minutiae, as Metzner uses the somewhat obscure Fresson process to make her prints. Developed in France in the late 1890s by Théodore-Henri Fresson, it is essentially a direct carbon printing process, resulting in photographic images that have the textural subtlety of a charcoal drawing. But the technical details of the proprietary process (initially only in black and white, and then adapted for color printing in the 1950s) were never patented or made public, making Fresson’s own lab the primary place to have prints made; now several generations of Fresson descendants later, this is still the case. Initially, the atmospheric Fresson process was employed by artists lumped under the Pictorialist banner, like Robert Demachy and Léonard Misonne, but in more recent years, the process has been embraced by a handful of contemporary photographers who have adapted its nuances to their own points of view, as seen in the moody landscapes of Bernard Plossu and the sensual Polaroid still lifes of Cy Twombly.

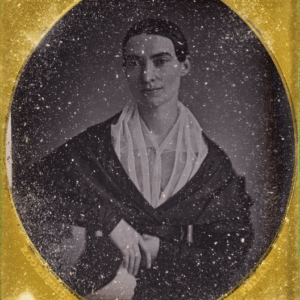

Metzner’s embrace of the Fresson process starts in the late 1970s and a few of her earliest experiments are included in this show, softening the surfaces of a standing portrait (from 1980) and turning a reclining nude into a luxuriating symphony of skin tones that drift toward light orange (also from 1980). By the mid-1980s, Meztner seems to have artistically developed the key to matching editorial subjects with the Fresson aesthetics, as the notable fashion and celebrity images that leverage her lush aesthetics seem to come in bunches. She mixes partially nude women with diamond necklaces and splashes of flowers. She creates a memorably evocative kiss between a Roman statue and an elegantly wispy-haired model. She poses a reclining woman in a shiny dress in a textural Art Deco setup. She makes visual connections between models in boxy dresses with shoulder pads and close fitting hats and sinuously geometric modern sculpture. And she finds tender romance in a seductive embrace near an Egyptian statue. Again and again, she takes the hard edged angles of 1980s fashion and turns them into atmospheric sensuousness. She even does this with a portrait of none other than Robert Mapplethorpe, whose standing pose in a long leather coat near some still life flowers turns his own motifs into her own, with the shadowy blue of the wall behind him creating a mood unlike anything in his art.

As the years of the 1980s slowly click by, we can see Metzner gaining confidence and applying her unique Fresson aesthetics to a wider range of possible subjects. A smoky-eyed Brooke Shields captures the essence of 1980s cool in 1985, but in the same year, Metzner also makes richly burnished and indeterminate still lifes of silvery metal objects. Soon afterward, she turns to elemental nudes which bring soft romance back into the picture, and then pushes on to close up florals in velvety sepia tones and views of New York City landmark buildings in various states of grainy almost approximate light and dark. Through the next few decades, these themes come and go, refreshed again and again by Metzner’s embrace of the subtleties of the Fresson process and how it can enable her compositions to be more hauntingly and languidly expressive.

From the vantage point of seeing these photographs again in 2025, I found a fascinating tension percolating in the room, where their very of-the-moment-of-the-1980s datedness tussles with a broader kind of seductive timelessness. Which brings me back to those passionate collectors who seem to want to be active evangelists for Metzner’s work – these pictures aren’t for everyone, but if they happen to line up with your own sense of fluid pictorial romance, they hit the target in the direct center over and over again.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced between $10000 and $61000, based on size and place in the edition, with one print marked price on request. Metzner’s work has only been intermittently available in the secondary markets in the past decade, with prices ranging from $2000 to $8000; with so few lots placed up for sale, these prices may not entirely reflect the actual market for Metzner’s best work.