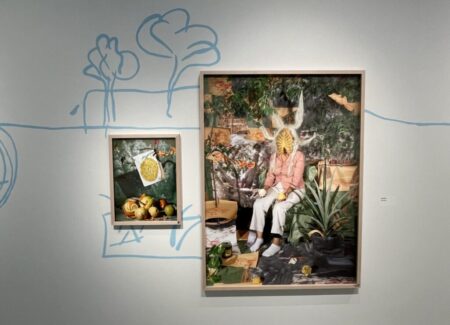

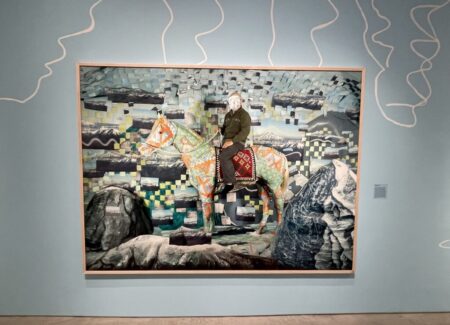

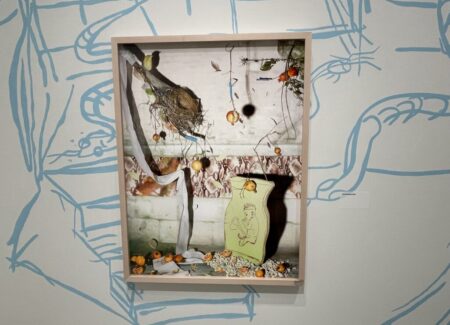

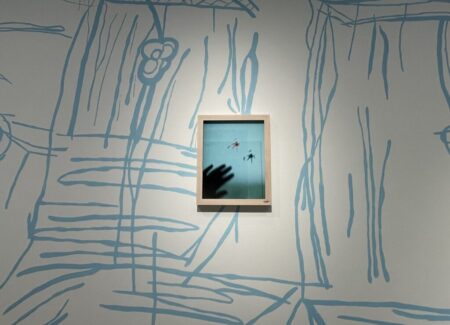

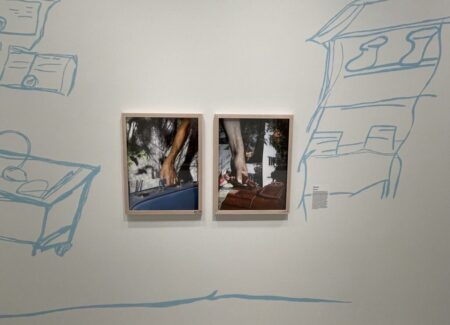

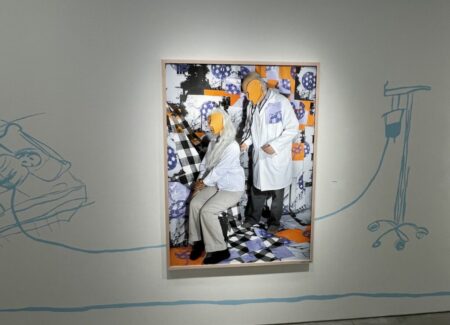

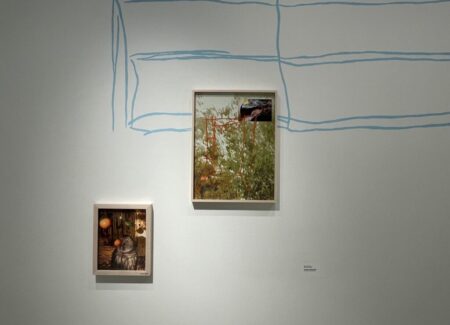

JTF (just the facts): A total of 43 color photographs, framed in light wood and unmatted (some of the frames feature ink stamps in the corners), and hung against white/light blue walls with light blue/white drawings in a series of rooms on the second floor of the museum. The show has been curated by Elisabeth Sherman. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the exhibition:

- 36 pigment prints, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025

- 7 chromogenic prints with screenprinting, 2025

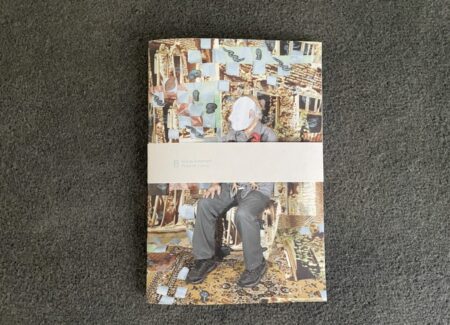

This body of work has recently been published in a zine by Matarile Ediciones (here). Saddle stitch staple bound with rubber-stamped obi band, 5.5 x 8 inches, 32 pages. In an edition of 300 copies. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: In the past decade, Sheida Soleimani has slowly been building an artistic name for herself, via the usual emerging photographer path of some initial projects, a handful of smaller solo gallery shows, and the inclusion of her work in various group shows and international art fairs. This exhibit finds her making the important career jump to the institutional level, with a solo show of recent work on view at the ICP in New York. The installation expands on a project first seen in 2023 (reviewed here), adding recent images to her ongoing “Ghostwriter” series as well as introducing related pictures from a new project “Flyways”. In general, an early career museum exhibit like this one is an acknowledgement from the art world establishment that an artist’s work is resonating with curators and wider audiences alike, so Soleimani’s art world star is clearly on the rise.

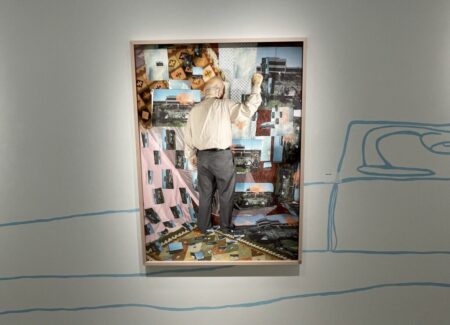

To date, Soleimani has largely bypassed a traditional observational approach to photography, and instead cast herself as an expressive builder of installations, in that she meticulously crafts elaborate studio-based setups that she ultimately photographs. At first glance, many of her images mimic a chaotically digital look-and-feel, with sculptural still life setups and portrait sitters layered against dense checkerboards of allusive pixelization, collaging a carefully selected range of appropriated image sources and visual references together; a closer look reveals that Soleimani’s installations are resolutely handmade, often with inexpensive paper prints that subtly reveal their gaps, edges, and shadows.

In much of her earlier work (as seen in a 2020 gallery show, reviewed here), Soleimani expanded outward from her Iranian-American heritage, artistically exploring the social, economic, and geopolitical events taking place in Iran and in the larger Middle East, often with a caustically satirical eye. What became clear even back then was that Soleimani’s art was filled with very specific visual references to Iranian culture and society, and that she was remixing those deliberate visual choices and cues into carefully controlled assemblages that juxtaposed those ideas in sophisticated and often surreal ways. While these works were consistently visually vibrant and engrossing, for outsiders to her cultural framework (like myself), her pictures could often feel like puzzles that could only be entirely deciphered and appreciated with someone on hand to explain all the relevant details.

Soleimani’s recent “Ghostwriter” series leverages this same hand-crafted set-piece visual vocabulary, but turns inward and applies it to the origin stories of her own family. In particular, Soleimani dives into the stories her parents told her about their lives in Iran – he was a doctor, she a nurse, and they were both pro-democracy activists, who then fled the country as political refugees after the Islamic Revolution. The family lore then continues with each parent taking his or her own circuitous route of migration to the United States (each with just a single suitcase), where they then rejoined each other and built a new life, neither of them able to continue practicing medicine. Soleimani’s image tableaux reprocess these received memories (hence the “ghostwriter” title), using layers of symbols and visual references to tease out more potent associations and resonances.

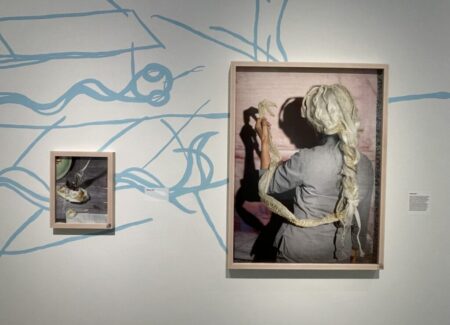

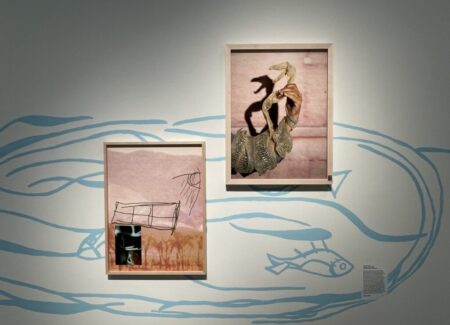

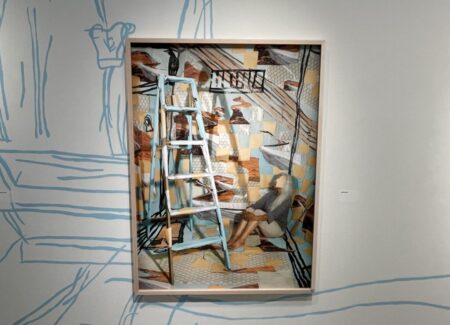

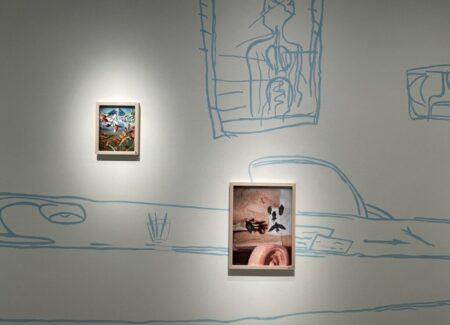

The installation of “Panjereh” (which is translated from Farsi as “window” or “passageway”) is boldly eye catching, with large gestural illustrations floating underneath Soleimani’s framed photographs, connecting them together. The drawings were made by Soleimani’s mother, and add a second expressive version of the events being pictured, linking each of the individual episodes into a broader flow of collective memory and interpretation. In many of these scenes, Soleimani has used her parents as subjects, their faces generally covered by paper masks, but their personas otherwise visible. Some of the images are readily identifiable as stylized, almost magical realist versions of actual events – we see Soleimani’s father dressed as a doctor, the two parents with fists raised in protest, two hands holding suitcases, and the father on horseback (apparently part of his journey out of Iran included a horse). Other scenes featuring the parents are more expansively symbolic, like the father riding on a magic carpet, the mother with snake skins curled into her hair, the mother sitting near a ladder (evoking the child’s game of Snakes and Ladders), and the two parents making a “telephone” connection with tin cans and another snake skin. In this way, Soleimani has created physical spaces where her family’s memories can flourish, each theatrical set expanding the reach of the original narrative.

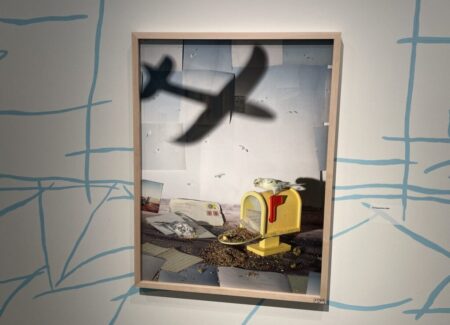

These larger portraits are then balanced by more intimate still lifes and smaller arrangements, many populated by birds. Some of the backstories and reference points to these pictures are explained on the nearby wall labels, including a Persian fairy tale told to the artist by her mother featuring fruits with faces and a pair of golden scissors, the revolutionary symbolism of red tulips, and the partridge as the national bird of Iran, making the image decoding process a little easier. The larger bird connection requires a bit more explanation – when Soleimani’s mother was unable to continue her nursing after moving to the United States, she turned to caring for animals and plants at a local wildlife rehab center, an interest she passed down to her daughter. One assemblage featuring birds is decently straightforward, mixing birds, birdseed, and images of birds in flight with airmail envelopes, a mailbox, and the silhouette of an airplane, alluding to flight in many forms. More obscure are setups featuring a crow with some walnuts, an owl with citrus fruits, a car mirror (with the face of the mother partially reflected) with some scorpions, and the seedy interior of a melon covered by a huge black bug, each likely supported by memories that are more apparent to the family members than to the viewing public. Still other images feature the feeding of a baby bird and the releasing of a bluebird through the “bars” of a cut photographic print, more clearly referencing the attentive fostering of birds by both mother and daughter.

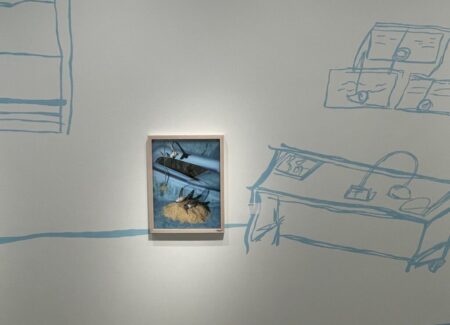

As it turns out, Soleimani’s commitment to the well being of birds was so strong that it became a day job of its own. The artist founded an organization called Congress of the Birds (here) in 2018 that cares for and rehabilitates wild birds in Rhode Island (where Soleimani lives and teaches), and this activity has then spilled back into a new series of artworks called “Flyways”, a handful of which are intermingled into the flow of this show. Each of these works combines three separate elements – an image of an injured migratory bird, often seen up close; a cropped scan of one of the photographs from a early roll of color film taken by the artist’s mother while she was still in Iran; and screenprinted markings, in grids, blocks, squares, and other loosely hand-drawn forms that might represent buildings (the kind that routinely injure birds in flight) or other structures that impose control (like prisons, as experienced by those that rise up against governments, including her parents.) The resulting montages feel surprisingly fragile, the safety of the trees and skies in the backgrounds interrupted by the gridlines, leading to real life damage and suffering for those in flight (in one way or another).

The durable significance of this exhibit lies in the way Soleimani has created her own unique visual language, one she can adapt to different kinds of storytelling and memory processing. In new and intellectually sophisticated ways, she’s creating opportunities for assemblage and compositing that go beyond the traditional boundaries of photocollage. That she’s then applying these approaches to themes, motifs, and urgent interests from her life as an Iranian-American further distances her works from things we’ve readily seen before. Hopefully, this handsome museum exhibit will give her a well-earned boost of confidence and exposure, that she can then leverage into the forward drive necessary to keep innovating.

Collector’s POV: Sheida Soleimani is represented by Edel Assanti in London (here) and Harlan Levey Projects in Brussels (here). Soleimani’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.