JTF (just the facts): Published in 2013 by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (here) and Delmonico Books/Prestel (here) to coincide with an exhibition of the Vernon Collection organized by LACMA (October 27, 2013-March 23, 2014). Hardcover (8 ½ x 12 ½ inches), 224 pages, with 198 black-and-white photographs and 11 color photographs, priced at $49.95. Essays by Britt Salvesen, Antonio Damasio, Alan Gilchrist, Pietro Perona, Barbara Maria Stafford, and a conversation between Todd Cronan and James Welling. (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Marjorie and Leonard Vernon began to buy photographs in 1975 when, for about $1000, one could own classic images from almost any period in the history of the medium. (Top price for rock star Ansel Adams that year was about $400.) Guided as much by their own taste and instincts rather than market strategy, the Vernons ended up with more than 3,600 prints (dated 1839-2001) by some 700 artists and, I’m guessing, paid less than what it now costs to outbid billionaires for a so-so Francis Bacon triptych at auction.

LACMA’s acquisition of this superb collection in 2008 (with financial aid from the Annenberg Foundation) deserved a catalog, and curator Britt Salvesen has organized a unique one to accompany the inaugural display. Closing next week, it is worth a visit by anyone in the L.A. area. The reproductions here, sad to say, don’t measure up to the quality of the originals in the airy installation, which is unusually generous in the space between each group of pictures.

The curator has used the occasion of the debut not to relate how the donors assembled a collection on this scale but rather to deliver her own take on photographic history. If her essays and those by others, highlight a timeline of discoveries in the psychology of perception—emphases that don’t always square with the Vernons’ more art-oriented mindset—her tangents are logical and her framework for the artists here leads to some felicitous pairings.

Instead of a strict chronology or a series of eras based on artistic credos, Salvesen has divided her roster of photographers into four groups, according to impulses and motivations she views as common across many decades. Although photographic history has been shaped by what could (or couldn’t) be recorded or seen at a given time, this is not a story of patents for film, shutters, lenses, and camera bodies. Nor do journals or corporations play a decisive role. The narrative is more apt to locate the kind of pictures made in, say, the 1880s or the 1920s within a zeitgeist determined by evolving theories of the mind’s eye.

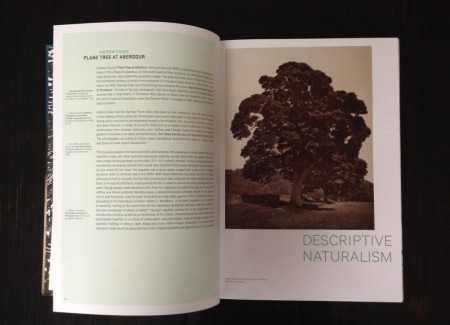

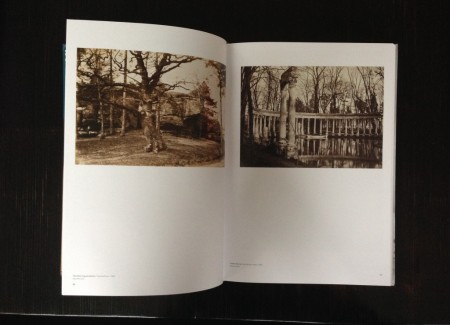

“Descriptive Naturalism” is the first mode she identifies. A tool for documenting nature as well as feats of engineering or architecture, for preserving history, and portraying “individuals both notable and ordinary,” photography quickly became indispensable as a translator of contemporary experience, a role it has never abdicated. The catalog quotes Lady Elizabeth Eastlake, who by 1857 viewed photography as answering “the craving, or rather necessity for cheap, prompt, and correct facts in the public at large.”

In this taxonomy, William Henry Fox Talbot’s “Articles of China” (c. 1843) belongs with August Sander formal portraits of 20th century German and Tony Ray-Jones’s snapshot of London men napping on an embankment (1967). Judy Fiskin’s pint-sized domestic exteriors and interiors from the 1980s aren’t so different from Walker Evans’s facades from the 1930s. More daring is Salvesen’s coupling of an Andy Warhol sewn photograph of four Assyrian statues at the Met (1984) with Charles/Jane Clifford’s portrait of a Spanish suit of armor (1866). Warhol is so often enrolled in the subversive army of Pop or Conceptual artists, it’s easy to forget that he liked cameras because they were foolproof, matter-of-fact picture-making machines—the same qualities that has enraptured everyone from the Victorians to the Instagrammers.

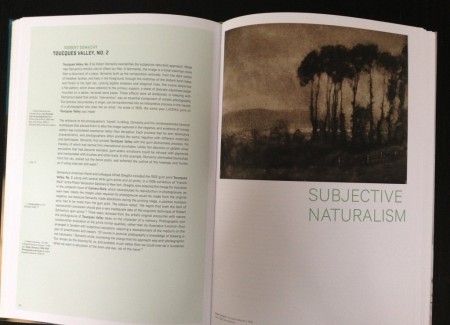

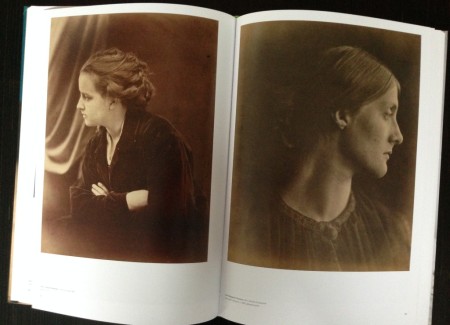

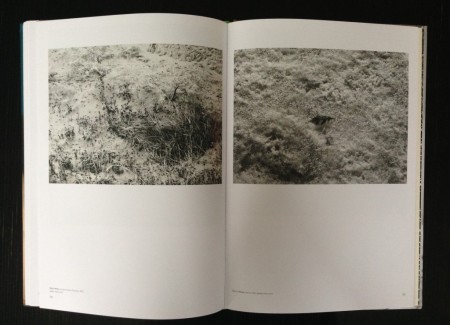

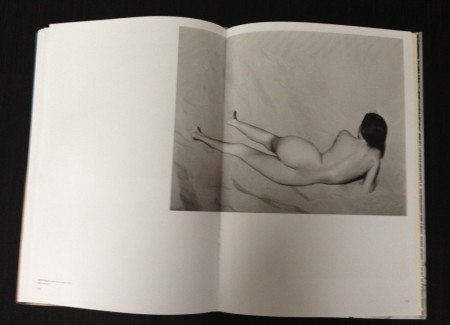

“Subjective Naturalism” is Salvesen’s way of dealing with Pictorialism and its recurrent guises, be it work by the Linked Ring artists or the Photo Secessionists or Josef Sudek or Sally Mann. Julia Margaret Cameron, Alfred Stieglitz, Frederick Evans, and Heinrich Kuhn are here, along with the young Edward Weston. By emulating other arts, notably Impressionist painting and Japanese graphics, these artists sought to resolve what an 1866 Art Journal had objected to about photography after its first decades of success: “There is in all photographs, or photographic prints, a want of what we may call texture…. There are no touches—no wondrous lines which show that the pencil was held by a master’s hand—no traces of the artist’s mind. All is just what is expected, cold, dry science.”

Salvesen prefers to see these artists as responsive to another sort of science: the emerging, inner-directed discipline of experimental psychology. In lecture halls and laboratories of German-speaking countries during the 1850s and 1860s, the physicians Hermann von Helmholtz and Wilhelm Wundt had begun to discuss and rigorously study sensation, time-reaction, fields of vision, and other mutable states of consciousness.

“The subjective naturalists made their case for photography as an expressive art,” she writes, “not only by emulating traditional media but also by redefining the photographer’s task, much as experimental psychology redefined the act of observation.” The same willed awareness required of a subject in a Wundt experiment was also required of an artist, or so thought Peter Henry Emerson. (Salvesen cites William James’s writing about “habits of attention.” She might have brought his brother Henry into this section as well. His dramatic method of presenting characters through a fine mesh of introspection was dismissed as antique and precious by critics in the 1920s. When they reread him during the 1940s, in light of Proust and Woolf, he was seen as the founder of the modern psychological novel. So far the Pictorialists have not been so fortunate, despite repeated curatorial efforts, like this one, to rehabilitate them as explorers of inner landscapes.)

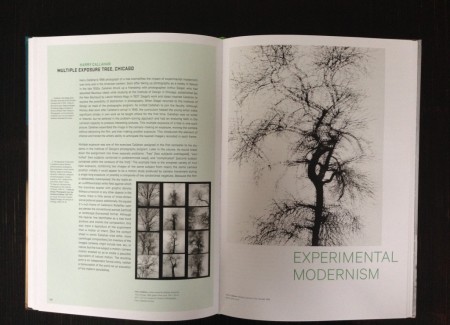

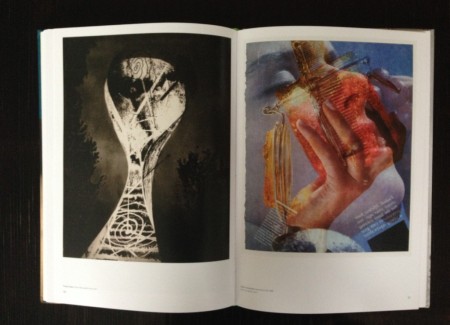

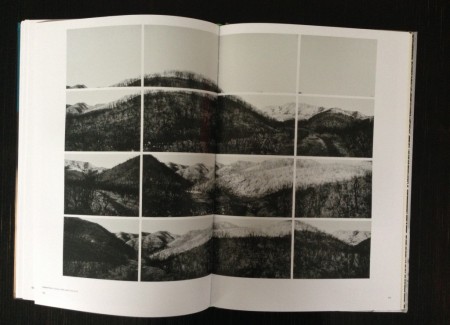

The 1920s are, for Salvesen, where photography branches into her two last categories. “Experimental Modernism” favored abstraction, fragmentation, angularity, distortion, ambiguity. Everyone from Eadweard Muybridge to Man Ray, Albert Renger-Patzsch to the Bechers, Berenice Abbott to Harry Callahan, Piet Zwart to Frederick Sommer is deposited here. By locating the pedagogical home for this mentality in the Bauhaus, and identifying its key figures as László Moholy-Nagy and György Kepes, she may not be saying anything we haven’t heard before.

What is newer is the stress she puts on Gestalt Psychology in their teachings. Moholy and Kepes believed that students had to train their brains in the new visual language of photography and film and that its/their radical possibilities surpassed anything yet done by Cubists or Futurists in reflecting the fraught excitement of modernity. Promising as this line of research may be, by focusing almost entirely on perception, and failing to mention the Russian Constructivists or the importance of revolutionary politics of any kind on the art of the ‘20s and ‘30s, this section is perhaps the weakest of the four.

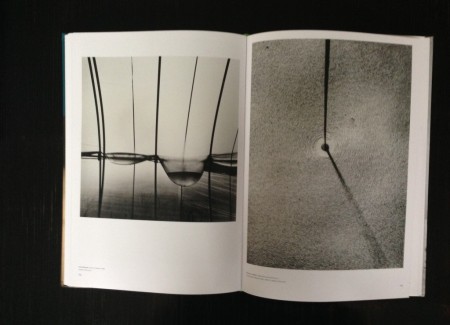

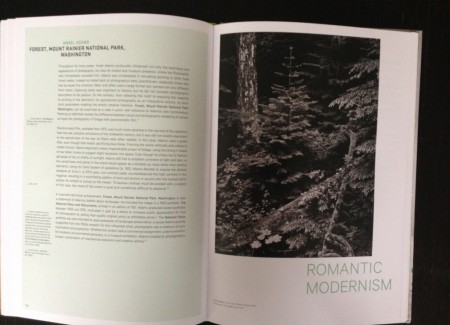

“Romantic Modernism” developed, in Salvesen’s schema, along a parallel and sometimes intersecting road during the 1920s. Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter, Minor White, Wynn Bullock, and Robert Adams are a few who have “tempered their reliance on apparatus with a reverence for nature.” This approach is neatly summed up in the wall label: “if the experimental modernist photograph was a manifesto, the romantic modernist photograph was a poem: inspired by nature, isolating moments of direct personal contact with the world, and offering signification on multiple levels.”

These artists formed the heart of the Vernon’s traditional collection. The catalog has room to reproduce only a few of the lesser-known prints in this style that they picked up, such as “Cutting Lettuce, Salinas, California,” (1938) by Dorothea Lange and “Conversation Near the Statue” (1933) by Manuel Alvarez Bravo. The show, but not the book, features prime examples of work by Roy DeCarava, Danny Lyon and many others.

Salvesen’s categories are, of course, permeable. Margaret Bourke-White’s “Fort Peck Dam, Montana” (1936) is teamed with other architectural images in “Experimental Modernism,” but could as easily join “Romantic Modernism.” Some artists make multiple appearances: Edward Weston is in three of the four categories and should probably be in “Descriptive Naturalism” as well.

The advantage of her flexible boundaries is that artists are not reduced to one period of their career. Berenice Abbott was as interested in photographing science experiments as she was in architecture. Weston had several phases: gauzy Pictorialist, left-wing ex-patriot, international promoter of Modernism (who chose the photographers for “Film und Foto”), and Romantic interpreter of California’s deserts and seashore.

The disadvantage is that the categories can become so porous they become an unreliable net for catching and examining artifacts. Photography had from its first decades all of the four characteristics that Salvesen outlines, and then some. The number of applications for the medium (however loosely defined) continues to grow.

Of course, Salvesen did not intend for her history to be comprehensive. The catalog and exhibition are a result of her inheriting this enormous collection. Although it stops in 2001, before digital, and has other sizable holes, especially in non-traditional post-1960s work, it’s a marvelous gift for LACMA. Faced with the task of explaining the contents for others, Salvesen clearly didn’t want to tell the same story we’ve read before in the many 150th anniversary celebrations in 1989. It’s as unconventional a history as she could manage under the circumstances. For asking us to look and think in a different way at 162 years of photographs, many of them familiar and interpreted by others many times before, one of our best photography curators deserves our thanks.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum group show surveying a broad swath of photographic history, we will dispense with the usual discussion of primary and secondary market prices.

One of your best reviews, in my opinion, of an interesting curating challenge taken on by Britt at the top of her game.

Compartmentalising issues aside, simply appreciating ‘vintage’ photographs is a challenge in itself, their original meaning and effect is drowned out by the humoungous clamour of the many generations of newer images that have followed and they, naturally, now look dated and quiet, even VERY dated, and silenced. But sometimes it’s possible to time-travel back in the mind, to trick oneself into re-living those unique moments when long dead art photographers discovered new ways to say things and new things to say, to experience the electrifying thrill, shock even, of their brand new images the like of which had never been seen before. Mostly produced with little prospect of financial return or regard, and at best with a potential audience worldwide of perhaps no more than a few thousand interested persons – but often far, far less, maybe a partner and a few friends.