JTF (just the facts): Published in 2014 by the Art Institute of Chicago and distributed by Yale University Press, this is a companion volume for the exhibition Sarah Charlesworth: Stills, at the AIC from September 18, 2014–January 5, 2015 (here). Hardcover, 64 pages, 7 ¾ x 10 ¾ inches, 8 color and 18 black and white photographs. Includes an essay by Matthew S. Witkovsky and a conversation between him and Matthew C. Lange. $25 (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: The unexpected death of Sarah Charlesworth in 2013 was a shocking loss to the art community in New York and beyond, as well as to her many students and ex-students. A prominent member of the so-called Pictures Generation, she was an artist whose forceful words (as co-editor with Joseph Kossuth of the Marxist journal Fox) and cerebral work, exhibited regularly since the late 1970s, revolved around the contextual meaning of images.

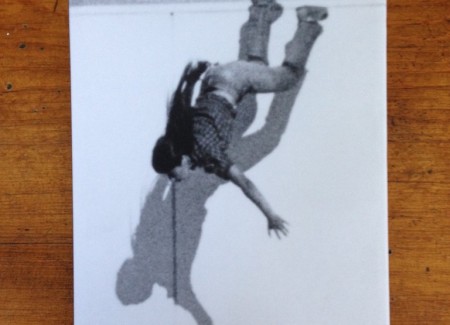

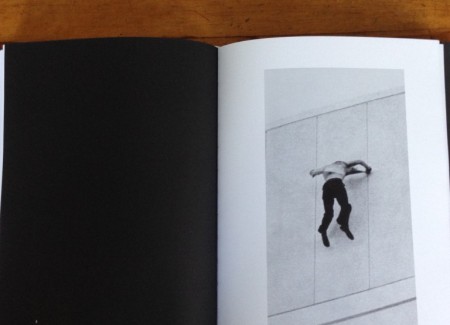

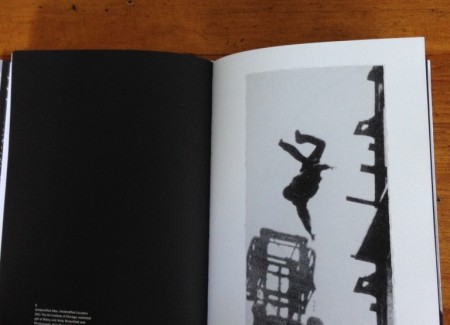

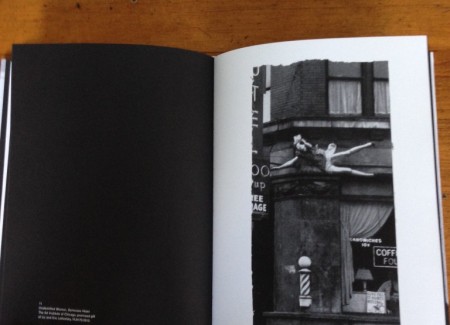

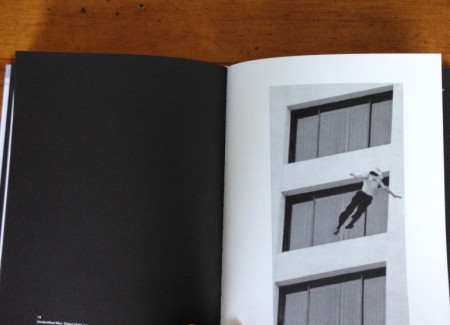

This slender volume is the first of what will certainly be other monographs devoted to her work. It serves as the catalog to an AIC exhibition of Charlesworth’s 1980 series Stills—a set of 14 large scale black and white photographic images. Appropriated from various news sources, each of them depicts a person falling to his or her (likely) death from a towering height. She has blown up these photos to mural size (78 x 42 inches). Faces are for the most part blurry or obscured, and in some cases, neither names nor dates are given.

This family of images, common on the pages of tabloids during the 1960s and ‘70s, is guaranteed to provoke horror in the reader/viewer as well as fascination. The bodies are suspended in air, when gravity has taken over but not yet sealed their doom. Charlesworth’s pieces pose a queasy dilemma for our higher and lower selves, forcing us to choose between empathy for the suffering of others and our innate voyeurism. By the time our conscience kicks in, it’s too late: we’re rubberneckers, even if we’re embarrassed to admit that fact.

Stills is also about photography. The wonder that a picture machine allows us to witness the balletic reality of someone “caught” in mid-air—the raison d’être of sports photography—is balanced by the unreality that often results from photographic repetition of any event. Staring at someone’s impending death, when spread across the front page of a newspaper—in hundreds of thousands of copies, on paper stock designed to be thrown away—can seem like more of a sickening violation of a life than staring at that life ended, after the body has landed on the sidewalk.

In his essay Matthew S. Witkovsky, curator of photography at the AIC, analyzes Charlesworth’s work in relation to 1970s photoconceptualism and to even earlier appropriated images of tabloid seediness and disaster, such as Warhol’s Suicide from 1962. Whereas Michael Heizer and Mel Bochner in the early 1970s had enlarged photos in their work so that objects in them were “actual size,” Witkovsky believes that Charlesworth, by making human beings in her photos “actual size,” had “radically changed the terms of the discussion.” The scale of the figures in her works “suggested an equivalence between viewer and subject” that, he believes, is vital to our emotional reactions. (I can’t agree: the giant scale to my eyes diminishes their power.)

Witkovsky notes that Charlesworth showed 7 of these works in the New York apartment of artist/dealer Tony Shafrazi in 1980 and may have prepared as many as 70. She had also decided to restrict their production and make only one print of each image, the equivalent of “one work for one life.” The AIC show is a sample she had chosen in discussions with Witkovsky before her death. This is their first exhibition in 34 years.

His essay is insightful as far as it goes, albeit with surprising omissions. No mention is made of what is easily the era’s most famous photograph of falling bodies. Stanley Foreman was on the scene of a Boston apartment fire in 1975 when he happened to capture an African-American mother and child spilling through the air after a fire escape collapsed. (The 19 year-old woman died; her 2 year-old goddaughter survived.)

Featured on the front page of the Boston Herald-American and reproduced in over a hundred newspapers, the image earned Foreman the Pulitzer Prize and enormous controversy. Was it OK to expose to the world the sight of someone about to die? The woman was not a public figure and thus her death had no “news value,” as did, say, the 1963 photos by Bob Jackson and Jack Beers of Jack Ruby shooting and killing Lee Harvey Oswald, or the 1968 Saigon street execution photos by Eddie Adams from the Vietnam War. Nora Ephron wrote an essay about Foreman’s photograph and the ethics of publishing it for journalism and for society.

Another missing point of reference in the essay is Robert Longo’s Men in the Cities series from 1979, which depict stumbling bodies in poses eerily similar to ones in Charlesworth’s Stills. (Mad Men’s title sequence is a shameless rip-off of/homage to what some regard as the highlight of Longo’s career.) And although Witkovsky sensitively discusses the photos of falling bodies that were published during the collapse of the World Trade Center towers, an event that Charlesworth, of course, had not anticipated in 1980, he has nothing to say about Eric Fischl’s sculpture Tumbling Woman, from 2002, and the barrage of criticism inflicted on him when the piece was displayed at Rockefeller Center. Both of these artists were colleagues of Charlesworth and members of the Pictures Generation.

Space restrictions, no doubt, account for much of what I find lacking in the essay. Less forgivable is the silence about the legitimacy of reproducing someone else’s photographs. Too many artists and curators blithely pretend that the legal and moral issues surrounding appropriation are settled or trivial. They are not. Is it an accident that Charlesworth didn’t choose to “appropriate” Foreman’s photograph? Or did she gauge that it was too celebrated—and therefore protected by aggressive lawyers—to adopt for her own purposes?

It is sad and annoying that Charlesworth can’t contribute to these debates. Her work was, as Witkovsky writes, actively engaged in the contested space between public and private. A conversation here between him and Matthew C. Lange, one of her former students at SVA, discusses her plans for Stills and other projects, and what a challenging teacher she could be. “Sarah believed that for your work to be successful you should know precisely what you are doing,” says Lange. His reminiscence makes clear that she would have had plenty to say about these pieces and how much we’re missing by her absence.

Collectors POV: Sarah Charlesworth is represented by Maccarone in New York (here). Her work has only an intermittent secondary market track record; recent prices have generally ranged between $2000 and $12000, but this data only reflects a few transactions in any given year in the past decade and therefore may not be entirely representative of the actual market for her best work.