JTF (just the facts): A total of 12 color photographs, hung in black frames without mats on the white walls in the main gallery space, and one eight-minute film—playing on a loop in a darkened side gallery—all from 2017. The photographs consist of two 30×38” pigment prints mounted on Dibond; four 30×38” dye sublimation prints on aluminum; and six C-prints mounted on Dibond, four of them measuring 30×24” and two of them measuring 62×42”. All the works in the show, including the film, were produced in editions of 3+2AP. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: “What is ‘Dark Dark?’” asks the male narrator of Canadian-born photographer Sara Cwynar’s new film Rose Gold, as a 1960s product sheet for pressed face powder flashes on the screen. (“Dark Dark” is one of 12 shades of makeup on offer; “Natural,” far lighter, is another.) “Who is the voice of authority?’”

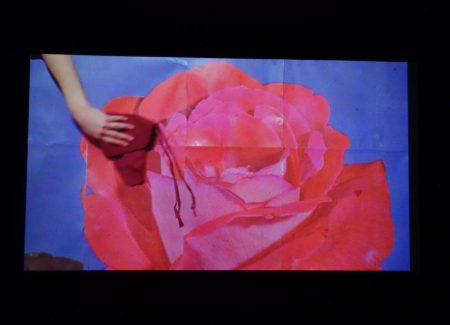

Titled after a color of iPhone introduced in 2015 for the iPhone 6S, Rose Gold is an exhilarating, rapid-fire sequence of images with overlapping voiceovers by two speakers, one male and one female. They read aloud the artist’s musings—sprinkled with quotes from the likes of Jean Baudrillard, Martin Heidegger, and Toni Morrison, as well as the Apple website and the Encyclopedia Britannica—on, among other subjects, desire, consumerism, individual experience, “soft” sexism, mimesis in nature, power, obsolescence, knowledge in the age of the Internet, and the politics of color. Objects, many of them from the 1960s and ’70s, are arranged, rearranged, polished, and smashed. The artist stalks her studio, sets up photo shoots, spritzes herself with perfume, and looks at her watch. Tourists ogle Hoover Dam, airplanes take off and land, Trump’s gold-toned Las Vegas hotel looms against a blue desert sky. The mood is hectic, with overtones of exhaustion.

The film serves as both introduction and key to the photographs accompanying it in Cwynar’s solo exhibition (also called “Rose Gold”) at Foxy Production. Over the past several years, Cwynar has produced an impressive body of photo-based work that includes set-up photographs; images from darkroom manuals distorted with a scanner; and photomontages created through a labor-intensive process combining straight and set-up photography, digital manipulations, and collage.

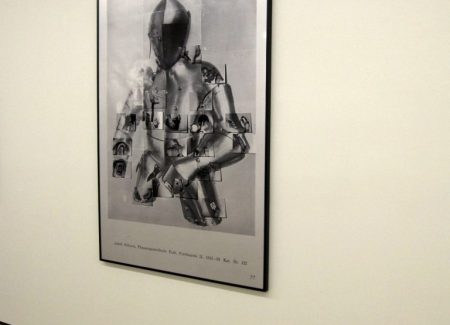

Two examples of this last type of image appear in the present show. Both are enlargements of black-and-white plates from a book on armor; upon closer inspection, they sport myriad tiny pictures of the artist’s hands holding a range of objects: a mirror, a vegetable peeler, an iPod. Seen on the Web, the pieces would no doubt simply read much as the original book plates would—a deliberate move on the part of the artist, who has said that she prefers her work to be legible only in real life. Yet, despite how they resist being consumed quickly online, Cwynar’s photographs frequently mimic the way that content is circulated, repurposed, recombined, and recontextualized on the Internet.

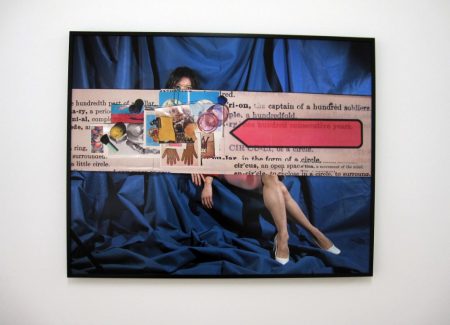

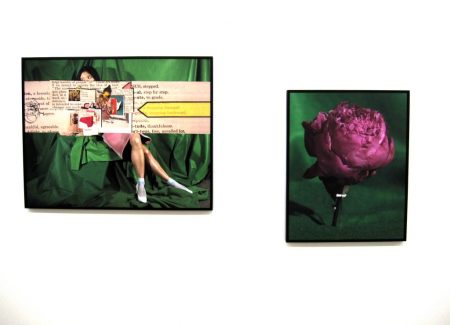

The show’s real reward, though, is a group of six images of Cwynar’s friend Tracy, a pretty young woman of Asian descent dressed in sweater, skirt, and heels, who seems to embody the exhaustion, if not the freneticism, felt in the film. In two of the pictures, Tracy reclines against a backdrop of gridded rectangles—enlargements of pages from a process color manual for designers—as if to match herself to the right shade. In four other photographs, her image is obscured by agglomerations of vintage items, including golf balls, perfume bottles, other people’s snapshots, and, tellingly, a knot of women’s stockings in a color still called “nude.”

In the “Tracy” series, Cwynar adds a new depth, both literal and conceptual, to her work. Scale—never certain in her photographs—is used to even more disorienting effect than in the past, and the sculptural impulses of earlier series find new and subtler expression. At the same time, she shows welcome signs of moving into new and productive territory where nostalgia and kitsch intersect with real life.

Like the “Pictures” generation of artists of the 1980s, Cwynar is interested in the role of mass-media images in constructing identity and desire. (In common with several of those artists, notably Richard Prince and Barbara Kruger, she has herself worked for mass-media publications, including a three-year stint as graphic designer at the New York Times Magazine.) Just as they did, she understands that images, no matter how banal, are never neutral. Nor, she suggests here, are colors.

And rose gold? Several tech sites are reporting that for many iPhone 7 buyers, black is back.

Collector’s POV: The photographs in this show are priced between $6000 and $14000 based on size. The film is priced at $18000. Cwynar’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail remains the best option or those collectors interested in following up.