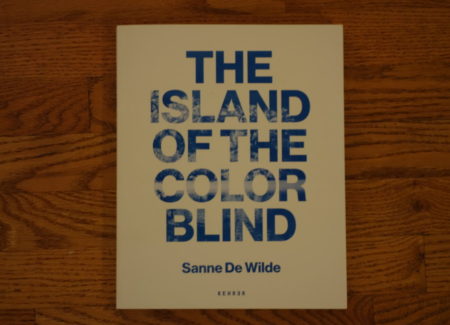

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2017 by Kehrer Verlag (here). Softcover (in UV-sensitive paper), 160 pages, with 85 color/monochrome reproductions. Includes essays/texts by Azu Nwagbogu, Oliver Sacks, Roel Van Gils, and the artist, as well as question/answer interviews with various inhabitants and an annotated family tree. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: The intricacies of human perception and the mechanisms of photography have a gloriously messy history of co-dependent interaction. When we think about taking a photograph of something, we are of course actually trying to directly connect brain and subject, albeit via two separate systems of processing and mediation. When we look, our eyes and optical functions process the incoming light and turn it into signals that are transferred to the brain; when we photograph, the light first goes through the camera’s lens and processing systems, where it is transformed into imagery via various combinations of chemicals and technologies, which we then unpack with our eyes to reach the final destination.

So when two photographers stand together and decide to photograph the ocean, the seemingly simple blues they are capturing have significant but often overlooked layers of complexity. Do their eyes even start by seeing the same “blue”? And as their cameras then convert the image to black and white, or break it down into component colors before recombining it to be output to screen or printed, how is that “blue” managed? Do all these transformations ultimately impact the nuances of “blue” on display? Do we actually capture what we see in some manner? And which “blue” is that exactly?

These thorny and often nested conceptual, philosophical, and technical questions lie at the heart of Sanne De Wilde’s thoughtful photobook The Island of the Colorblind. Much of the discussion around this particular book has centered on its intriguing backstory. De Wilde traveled to the isolated Micronesian island of Pingelap, where more than 5% of the population suffers from congenital achromatopsia, a rare hereditary condition in which the eye cannot detect color. (This is the same place that the neurologist Oliver Sacks chronicled in his 1997 book of the same name.) Through a combination of history, myth, and folklore, an engaging tale of typhoons, kings, and busy inbreeding emerges, explaining generations of maskun (“not-see”) children with the scales-of-grey-only eye disease.

But De Wilde’s photobook is much more than an outsider’s documentary study of the lives of these people. It is a layered meditation on the subtle nature of perception, one that forces us to consider what the world might be like if we saw it without color, and what color then comes to mean for those who have never seen it.

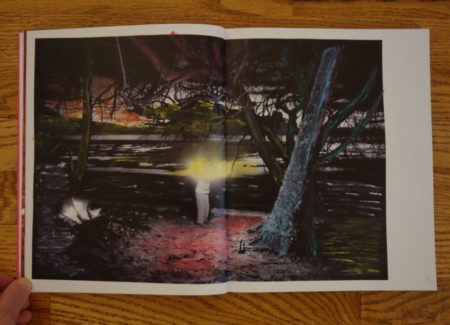

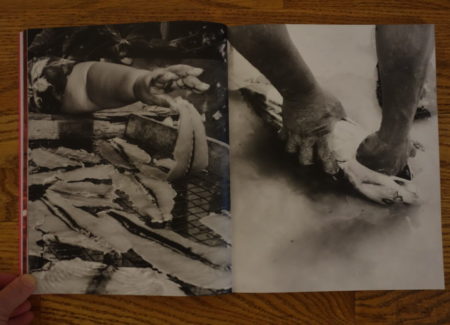

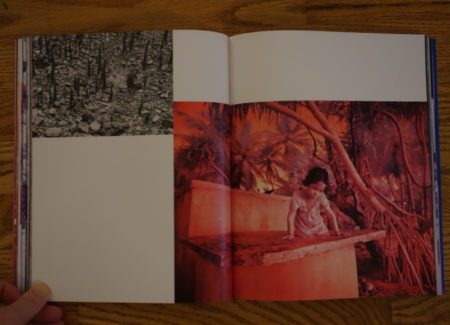

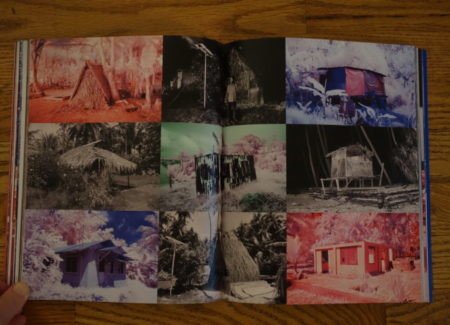

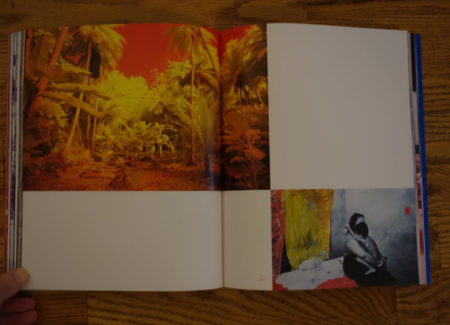

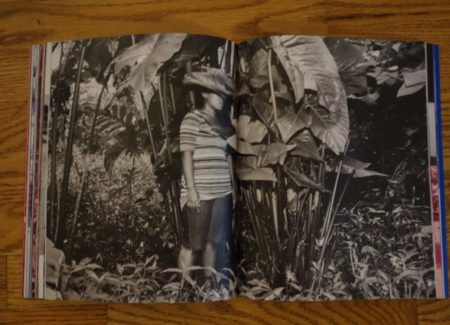

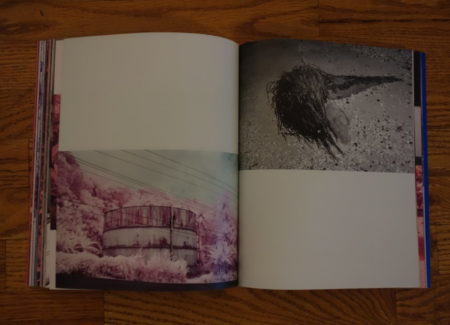

De Wilde sets the context with images of the island, its lush jungle vegetation, and the details of everyday life, from elemental fishing and tree climbing to the intrusions of modernity, in the form of a satellite dish, a trampoline, and several hulking concrete structures and buildings hidden among the dense tropical greenery. Many of the photographs are in black and white, mimicking what the environment looks like to the colorblind locals. What’s intriguing is how we are forced to see and understand these pictures – they aren’t artful monochromes deliberately turning color into shades of grey for aesthetic effect, but a version of reality that isn’t a transposition but a singular actuality. They are what the world looks like for the colorblind residents, a fundamental truth rather than an artistic decision. An extended tongue is grey not pink, an old dry palm frond is dark grey not brown, the sand is light grey not yellow, the massive elephant ear leaves are grey not green, and when night falls and the darkness becomes enveloping, De Wilde’s flash makes the contrasts even sharper. The subtleties of monochrome become a rich color scheme all their own.

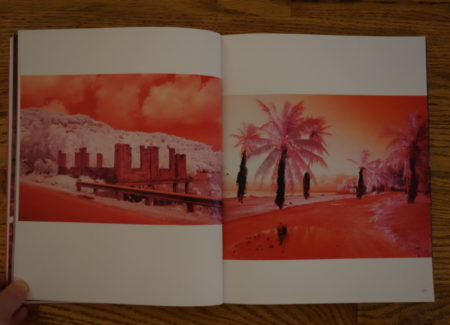

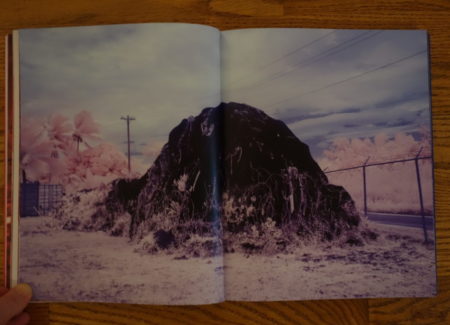

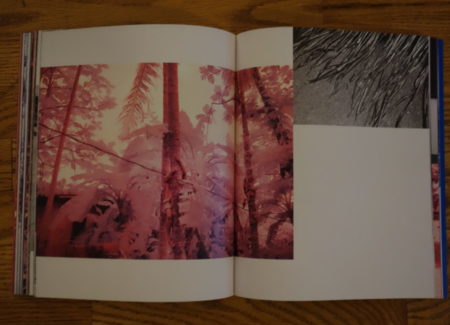

But De Wilde isn’t content to leave us there, communing with life amid the greyness. She interrupts this impulse with images in bright color, but not the normal full color palette we might expect. Instead she employs the disorienting inverted pinks and pastels of infra-red photography (think Richard Mosse), deliberately echoing or at least alluding to various specific forms of color blindness. These images seem to ask, if you didn’t know what color was, and someone described it to you, could this be what you imagine the world might look like? And so the sky turns red, the leaves turn a hazy cotton candy pink, and treetops, waterfalls, and clouds wander among washed out purples and light greens, like images from a magical fairy tale land. An image of a sprouting coconut is shown in a grid of four different versions, as if we might choose (or imagine) our preferred slice of reality.

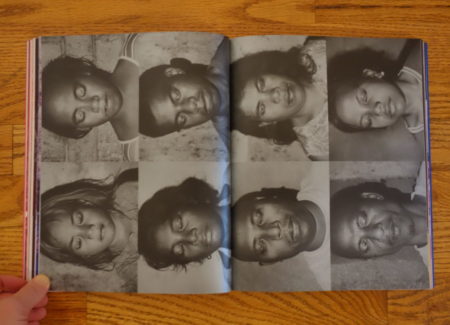

The mystical quality of those afflicted with color blindness comes through in De Wilde’s portraits. Standard headshots set against a concrete wall are made shimmery by being printed on silver paper, but the real magic comes in the treatment of the eyes. Whether the images are split second multiple exposures or just manipulations is immaterial, the effect is that each sitter seems to have eyes that are simultaneously open and closed, with a few spooky rolled back whites mixed in for further eeriness – what might be considered a handicap becomes a kind of possession or super power. Perhaps referencing their sensitivity to bright lights, other portraits consciously catch the color blind with their eyes covered, blocked, or interrupted (by a shirt, a clothesline, a leaf, or a handrailing), as if we aren’t supposed to be looking them directly in the eye.

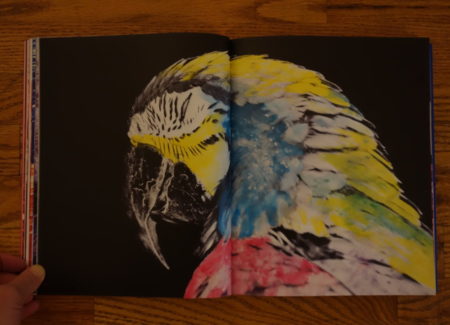

De Wilde continues her layered investigation of perception with two other mini-sections. In one, thin transparent paper is the foundation for monochrome images printed in red ink, where the image of a hand becomes a series of echoes and a man walking at night becomes a nude phantom. In another, when she was back in Belgium, the artist organized a workshop for a group of local achromatopic people and asked them to hand paint some of her black-and-white images. So the head of a parrot, a duck, and a sunset beach scene are touched up in color, but by people who don’t can’t directly see which colors are which, adding yet another unexpected inversion to the seemingly simple idea of what yellow feathers might look like.

When all these threads get woven together, The Island of the Colorblind successfully replicates the idea of consciously looking at the world through someone else’s eyes. Color becomes something that is both lost and found, real and imagined, applied and removed, so much so that De Wilde’s pictures seem to come untethered, each one both a document and an expressionistic alternate reality where the mundane is infused with surprising new beauty. Long after we have forgotten the specific island residents of Pingelap, I expect De Wilde’s rich meditation on the complexity of visual perception and the ephemeral nature of color will continue to resonate with satisfying cerebral uncertainty.

Collector’s POV: Sanne De Wilde is represented by East Wing (here) and the photo agency NOOR images (here). De Wilde’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so connecting directly with the artist via her gallery, her agency or her website remain the best options for those collectors interested in following up.