JTF (just the facts): A total of 31 black-and-white photographs, framed in black and matted/unmatted, and hung against white walls in the East and West gallery spaces. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 5 gelatin silver prints, 1975-1978/later, sized roughly 39×39 inches, in editions of 8+4AP

- 17 gelatin silver prints, 1975-1978/later, sized roughly 20×20 inches, in editions of 12

- 9 Ilford fiber-based glossy paper prints, 2008, sized roughly 64×48, in editions of 5+2AP

Comments/Context: One of the outcomes of taking a very long view of the history of photography is that such a vantage point naturally encourages the proverbial cream to rise to the top. Pick any subgenre of the medium and look out across a century of history (or more) and it becomes decently clear who the foundation artists were (or are) working in that narrow definitional slice of picture making. Of course, lists such as these are ever in flux and subject to constant revision, but if the artists have remained relevant in a particular genre after decades of exposure and study, there’s a pretty good chance they’re not there by accident.

The genre of the photographic self-portrait is so sprawling that it requires some further definitional sifting and sorting to be even a little manageable. One of the most important points of separation comes in the artist’s intention with respect to using his or her own body as a subject. In some cases, the artist’s body is simply present, documented, or almost anonymously manipulated (as in the case of Maier, Friedlander, Woodman, Goldin, Close, Coplans, etc.), with the artist implicitly acknowledging that the face or body in the pictures is indeed him or herself. But in others, the artist’s body is a vehicle for the aspirational crafting of identity and complex performative role playing. And when we turn our attention to this persona-driven world of self-portraiture, a murder’s row of shape shifting master photographers presents itself as historical context – Cahun, Warhol, Sherman, Mapplethorpe, Morimura, Fosso, and Wearing. The story of malleable photographic identity in the 20th century can’t really be comprehensively told without these names (and a few others) as a baseline.

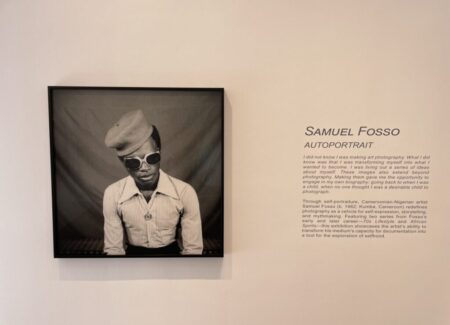

That Samuel Fosso belongs in this conceptual self-portraiture canon isn’t really up for scholarly debate, but this fact doesn’t mean that Fosso is as well known, or as well represented in key institutional and private collections, as he should be. While Fosso’s works regularly appear in surveys of African photographic portraiture, his presence in New York has been relatively intermittent, with a 2014 solo show at the Walther Collection (reviewed here) his last in-depth exhibit here. A new representation relationship with Yossi Milo will hopefully bring him back into the photographic conversation more regularly, with this powerhouse pairing of two of Fosso’s key series as a logical starting point.

For those with a glaring Fosso gap in their collections, prints from one or the other (or both) of these two projects would ably provide a flavor of his durable artistic importance. In a sense, this gallery show is actually two shows in one – a selection of Fosso’s early “70s Lifestyle” series in one space, paired with an installation of prints from his late 2000s series “African Spirits” in the other, providing a bookended dialogue of two different points in his career. For those with a 21st century mindset, the overarching structure of the show is a version of the “how it started, how it’s going” meme.

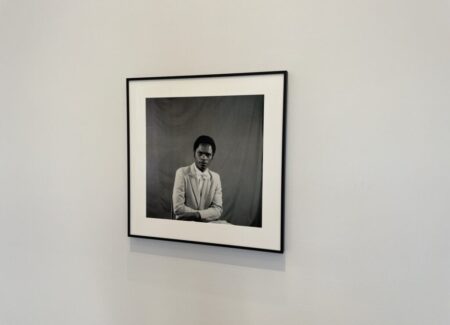

Fosso was essentially a photographic child prodigy. Born in Cameroon, he lived in Nigeria until civil war drove him to move to Bangui, in the Central African Republic (CAR). After an apprenticeship with a local photographer, he opened up his own commercial portrait studio – at the age of 13. His “70’s Lifestyle” series (made between 1975 and 1978, when he was in his mid teens) has its roots in the practicality of that business – his clients wanted quick turn around on their portraits, and Fosso didn’t want to waste the last unused frames on a roll of film by leaving them unexposed. So he finished off the available exposures with staged self-portraits, which he then displayed to promote his studio business or sent home to his family to Nigeria.

As seen in the nearly two dozen images from the series on view in this show, Fosso seemed to intuitively understand the performative aspects of photographic identity creation. His modest studio setup wasn’t unlike many we have seen in West African portraiture, with checkerboard flooring, patterned fabrics, curtained backdrops, a few painted murals, and some props – these were the tools of the trade, and the aesthetics expected by Fosso’s customers. But when he put himself in front of the camera, some magic started to happen. He was a naturally photogenic model, who seemed at ease posing in the fashions of the day, strutting around in bell bottoms, wide collars, and big sunglasses, pretending to be someone he aspired to be. He theatrically poses in white gloves and underwear, hides behinds bunches of cyclamens, imagines himself in European capitals, pretends to talk on the telephone, and gazes seriously into the camera wearing a formal suit, each setup allowing an improvised persona to emerge from the available materials. As a multi-faceted study of identity and self-presentation, made on the cheap at the end of the working day by an ambitious teenager, the images remain burstingly full of life and energy, so much so that when they were rediscovered in 1994 at the Rencontres Africaines de la Photographie in Bamako, Mali, they catapulted Fosso onto the international stage.

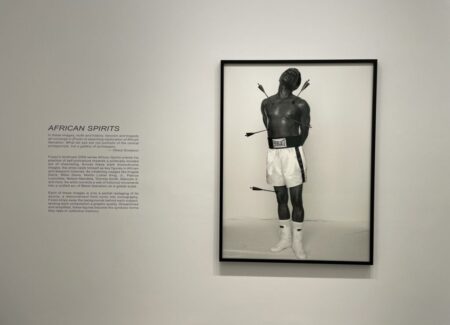

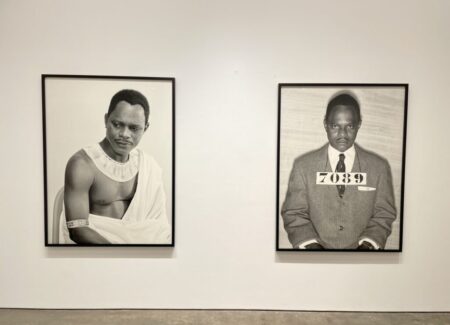

The second half of this show jumps forward more than thirty years, and brings us up to speed with Fosso’s self-portraits, which have evolved into a much more mature and conceptually sophisticated artistic practice. His “African Spirits” series (from 2008) finds Fosso picturing himself as a range of famous black athletes, musicians, politicians, and activists. In a total of 14 wall-filling large scale images (9 of which are on view here), Fosso meticulously restages famous pictures of Nelson Mandela, Angela Davis, Miles Davis, and Patrice Lumumba (among others), playing each role himself. Each work is precisely tuned to the original source photograph, with Fosso channeling Muhammad Ali as punctured by arrows (from a 1968 Esquire cover image by Carl Fischer), Malcolm X wearing a leather hat (from Eve Arnold’s 1961 portrait), and Martin Luther King Jr. with a police number (from his mugshot taken after his arrest at the 1956 bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama).

These are powerful pictures that dominate the gallery space, and the conceptual resonances they represent are many. Fosso is wrestling with ideas of celebrity, and overtly inhabiting well known representations of famous figures from black history. He is unpacking the circulation of photographic imagery through the media, and the way identity is constructed, aggregated, and stereotyped through photography. He is placing himself inside these figures, reinterpreting his own identity as influenced and shared by these others. And he is paying reverent homage to these heroes, while playacting in a kind of humorously playful (but serious) masquerade. The more you push on any one of these towering pictures, the more it shoves back, with challenging questions and complications that aren’t easily answered.

For those still catching up on Fosso, this tightly edited show is a perfect place to get started. It succinctly explains where Fosso fits and why he is important, and offers a thoughtful then and now pairing that clarifies how his unique brand of self-portraiture has continued to change over time. Of course, Fosso’s artistic story is much more compelling and nuanced than just these two individual projects, but part of a gallery’s job is to educate the audience, and this show succeeds at delivering an engaging first level Fosso primer that should encourage curators and collectors alike to dig deeper.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced as follows. The prints from “70s Lifestyle” are priced at $8500-9500 for the smaller prints and $22000 for the larger prints. The prints from “African Spirits” are priced between $40000 and $55000. Only a handful of Fosso’s prints have reached the secondary market in the past decade, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.