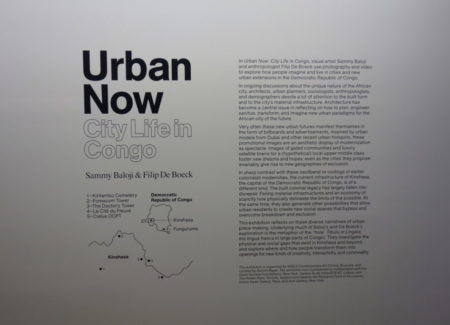

JTF (just the facts): A total of 40 large scale color photographs and 2 videos, framed in black and unmatted, and hung against white walls in the hallways of the ground floor, the stairway, and the lower level. No information about the photographic processes used, physical dimensions, or edition sizes was provided on wall labels or in the exhibition booklet. (Installation shots below.)

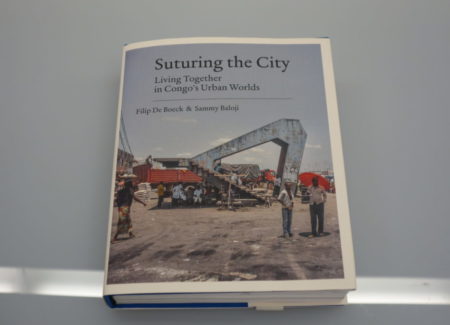

A monograph of this body of work, entitled Suturing the City: Living Together in Congo’s Urban Worlds, was published in 2016 by Autograph ABP (here). (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: Sammy Bajoli’s photographs of urban life in and around Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo try to unpack the underlying cultural structures hidden beneath the city’s varied surfaces. Working in partnership with the anthropologist Filip De Boeck, Bajoli has made images that incisively document the reality of the intermingled old and new, trying to make sense of the obvious conflicts and contradictions that percolate through the streets and nearby towns. Their combined vision repeatedly returns to incongruities, highlighting the unassuming or overlooked remnants of unfulfilled dreams and broken promises. In their eyes, the city is a place where stubborn pasts and aspirational modern futures tussle for control, and improvisational human creativity tries to make the best of the ever changing circumstances.

Architecture and its building-centric cousins land use, natural resource allocation, and commercial development together provide the interlocked scaffolding for this visual study. With these themes as their guide, Bajoli and De Boeck take us on parallel journeys down several discrete pathways, each terminating in a set of nuanced outcomes that provide insights into why the city looks (and operates) the way it does.

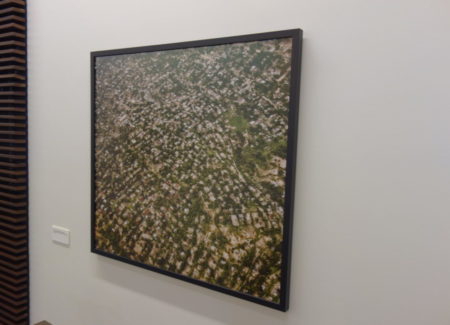

Their investigation begins on the crowded streets, where function rudely overrides form. The history of many African nations has been populated with architecture masquerading as progress, and Bajoli’s pictures tell us that the Democratic Republic of Congo is no different. Yet-to-be-built space age towers and spires seduce residents from fading billboards, the dreams of modernity now partially blocked by sheets of rusting corrugated tin. More generally, claims of a better life peer down from countess venues, the smiling beer drinkers and mobile phone users looking down on smoking piles of garbage, rotting canals, and standing water, with the indifferent bustle of everyday life going on all around.

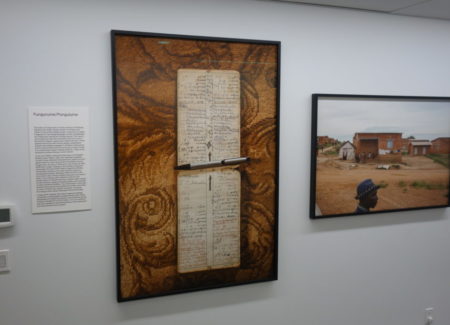

The architectural relics of the colonial past often linger in plain view, like rocks disrupting a stream. In one vacant lot, a set of angled concrete stairs climbs to nowhere, their usefulness reduced to providing a sliver of shade to the surrounding sun blasted market and minivan transit stop. Baloji and De Boeck make a more in-depth study of the OCPT building, a Modernist compound in geometric concrete once home to the local telecommunications company and a critical link to the outside world. Its once elegant screens and striations are soot covered and flaking, its vaulted interiors hollow and empty, now housing some 300 people in makeshift conditions. From the decaying satellite dishes to the hanging laundry, there is a dual sense of failure and reclamation, of the local people making practical use of the mysterious remnants and artifacts of the past.

In another line of photographic thinking, Bajoli and De Boeck follow the convoluted trail of local land rights and investigate their impact on both industry and culture. In recent years, inconsistent commercial interests have tugged the local communities in opposing directions, with various international partners coming and going as the political and financial conditions on the ground have changed. Copper and cobalt deposits have consistently attracted mining interests, and ambitious large scale projects have led to the forced relocation of residents. Bajoli’s photographs capture men sitting in front of their condemned homes, each with its mud walls tagged with red spray painted demolition numbers. Their faces are full of the resigned weariness of battling forces they cannot hope to overcome.

Another twisting tale follows the development of a South Korean agricultural project, which when it was ultimately abandoned was then taken over by locals and transformed into a successful land reclamation effort (Baloji’s photographs pose various local leaders in among the verdant fields). But those small victories have more recently been jeopardized by yet another new effort to build a private city, its pastel painted apartment blocks and swimming pools set incongruously in the wide open space, its luxuries seemingly out of touch with the needs of the people. And so the back and forth continues.

All of these development frictions rub against the traditional claims of the various tribes and their land chiefs. Bajoli’s portraits of these elders often have a king-without-a-throne feel to them, with stately men in ceremonial garb sitting in cheap plastic chairs or proudly holding symbols of power in cramped apartments with bare electrical wiring. These men represent the ruling authority of the past, but continue to play a central role in contemporary legal negotiations, and Bajoli’s pictures capture this dissonance of simultaneously protecting and impeding.

The sum effect of Bajoli’s photographs is a broad sense of ongoing struggle, where good intentions and folly seemingly impact the trajectory of the society with equal measure. The works are both documents and personal stories, pulling back to see the big picture and zooming in to give a human face to complex events.

Collector’s POV: Since this is effectively a museum show, there are of course no posted prices. Sammy Baoji is represented by Axis Gallery in New York (here) and Galerie Imane Farès in Paris (here).