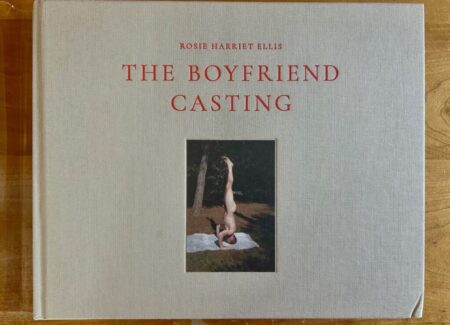

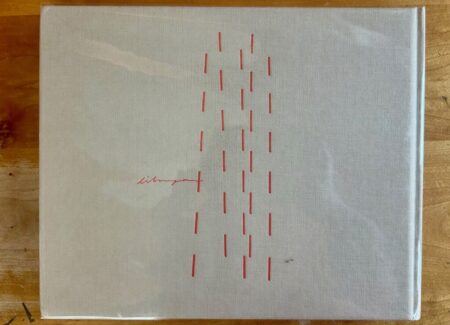

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2025 by Libraryman (here). Clothbound hardback with tipped in cover photograph, 29.7 x 24 cm, 160 pages, with 297 color and monochrome photographs. Includes a forward by Charlotte Jansen and numerous texts by the artist. Design by Tony Cederteg. In an edition of 700 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: The concept of “male gaze”—first articulated by Laura Mulvey in 1975—has been with us for only fifty years, but the trope has weighed on photography virtually since its inception. Traditionally (with some notable exceptions) men have positioned themselves behind the camera, while women have been posed before it, often in sexualized or passive positions. The power dynamics have dovetailed with patriarchal norms, as female objectification has been unconsciously internalized by the photo-consuming public, not to mention curators, critics, and practitioners.

This paradigm has persisted well into the new millennium. But the tide is turning. In the past few decades, the male gaze has been challenged in photography with increased regularity. Whether it’s Sally Mann documenting the ravaged body of her husband (reviewed here), Justine Kurland carving up the photobook canon (reviewed here), Laura Stevens casting an erotic lens on scantily clad men (here, for example), or Daniel Case exploring gay cruising grounds (reviewed here), various photographers have flipped the male gaze repeatedly on its head. By now it must be getting woozy.

The countermovement has taken an increasingly personal turn of late, with young women happily subjugating male friends and partners to their photographic wishes. Recent monographs from Pixy Liao (reviewed here), Caroline Tompkins (reviewed here), and Molly Matalon (reviewed here) proffer masculine physiques like prize pigs at a state fair. Go ahead and gaze your heart out, these women are in full control. They’ve come a long way from the fusty days of Man Ray and Edward Weston ravishing their viewfinders upon Lee Miller and Charis Wilson.

These predecessors have set the stage for The Boyfriend Casting. For male gaze rebuttals, Rosie Harriet Ellis’s debut monograph may be photography’s boldest stroke to date. Not that it is particularly rooted in feminist theory. Instead this book is largely driven by carnal appetites. While earning her MA from the Royal College of Art in 2018, Ellis’s budding passion for photography found a lusty target in her boyfriend Nick. His body became her muse and compulsion. “Nothing else mattered,” she writes. “I wanted him, his body, to see it, to touch it, to capture it…He needed my camera, and I needed him to want it.” Just like that, concupiscence and photography were fused into one. They remain intertwined throughout the book, across four related projects narrated by Ellis. Taken together they clock in over 150 pages, with hundreds of images filling a broad clothbound tome.

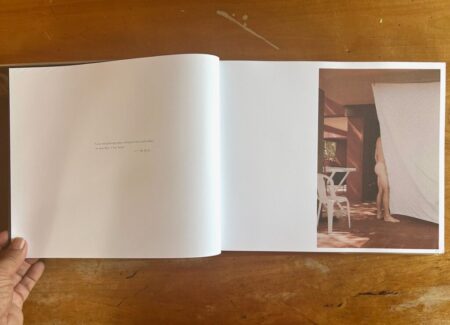

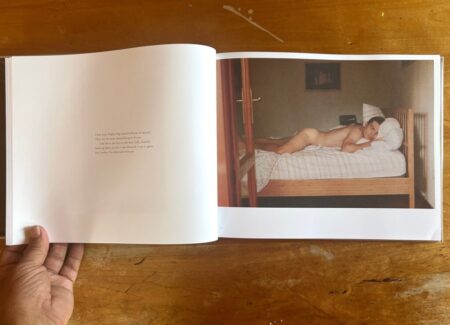

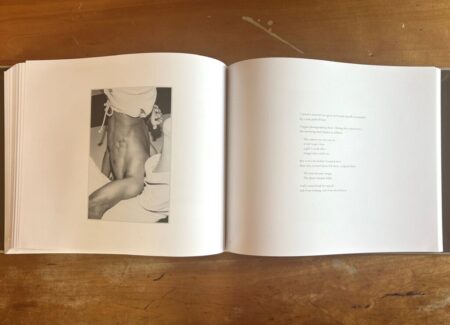

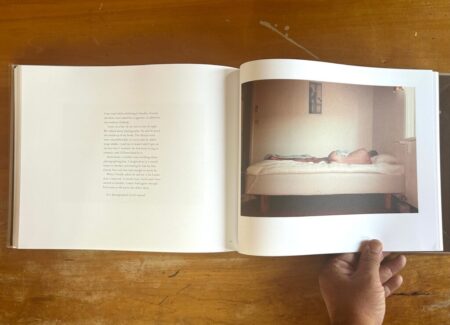

Ellis kicks things off with a bravado display of male form. She photographs Nick in one provocative pose after another. He lays in bed and on a towel, stands in the shower, and sits foregrounded before a white sheet backdrop. His pale body is an open book, young, unclothed, and rock hard. Ellis’s passion is implicit in the pictures. Look what I caught: a trophy BF! Meanwhile, Nick appears less enthusiastic. In most photos he stares somewhere off set, preoccupied with his own thoughts. In a few images he returns the camera’s gaze, but there’s no excitement. Are we done yet?, his expression seems to ask. “I’m obsessed with you,” replies Ellis. Her twin appetites are insatiable.

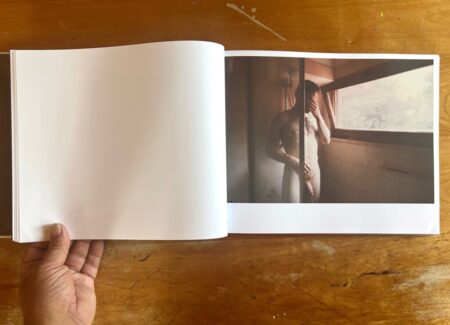

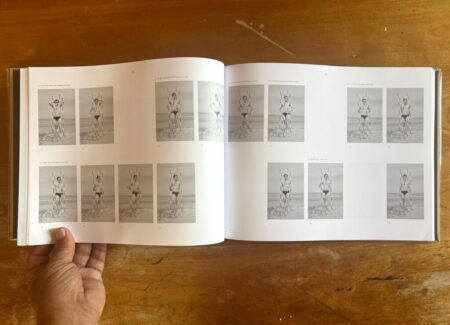

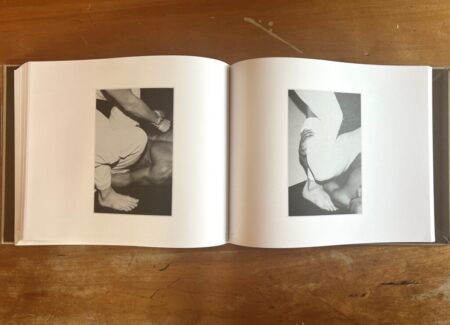

What happens next is no surprise. Nick eventually tires of the project and they split up. Adding insult to injury, he withdraws his consent to use the images already taken. This is a photographer’s worst nightmare, but Ellis is undaunted. She proposes an alternative. Nick can keep his undies on and his dignity somewhat intact, while she creates a new series of clinical Muybridge-style studies, “a catalog of gestures, every muscle, every shift recorded.”

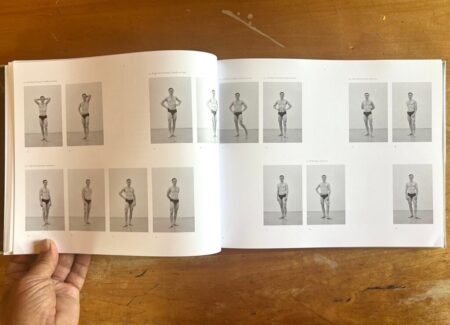

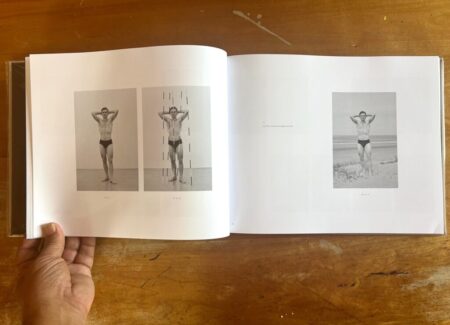

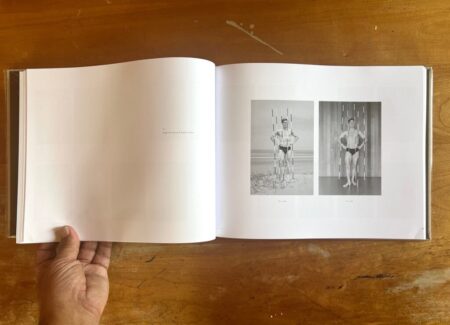

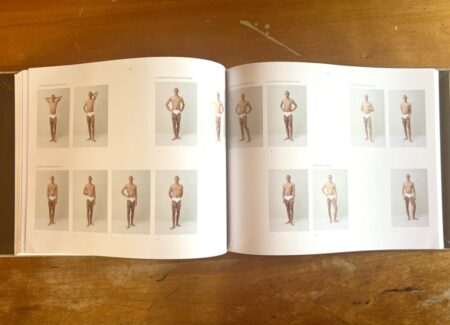

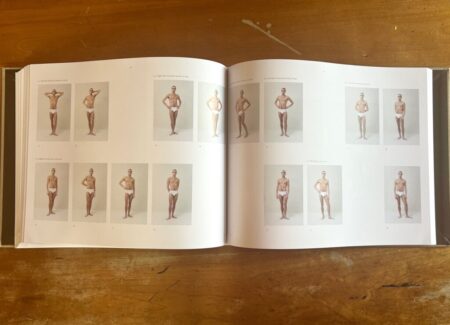

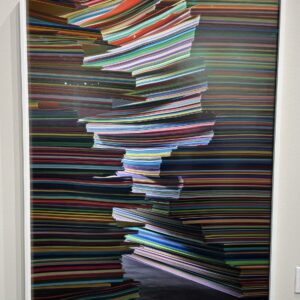

Nick agrees. Over the next few pages we see the results. He is photographed in serial fashion in the studio and on the beach, posed like an anatomically correct Ken doll under drab lighting. He puts one foot forward, then the other. His arms move slightly. He twists this way and that under Ellis’s direction. In some photos, his form is abstracted behind a fence of striped poles. All of these variations are arrayed into gridded verticals across several book spreads. They coalesce into the title series for The Boyfriend Casting.

Compared to the initial photos of Nick, this series is sexually neutered. The photos are monochrome and emotionally blank, closer to lab specimens than Playgirl centerfolds. Nick’s amorous charms have been emasculated. But perhaps there is power in raw analytics. For Charlotte Jansen, this title series is the most radical in the book, “a rare opportunity for the female viewer to emulate a predatory, voyeuristic way of looking.” Stripped of relationship baggage, these photos operate instead on pure bodily mechanics. They are measured, contained, and repeatable. “By adopting and objectifying the heteronormative male gaze and turning it on the male subject,” writes Jansen,”[Ellis] exposes its cruelty and primitiveness.”

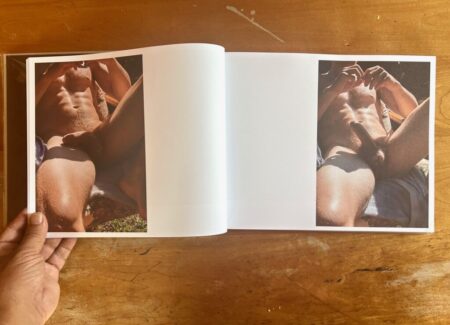

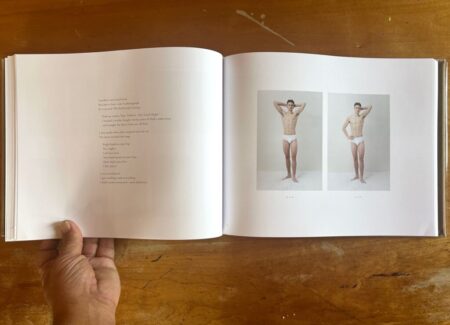

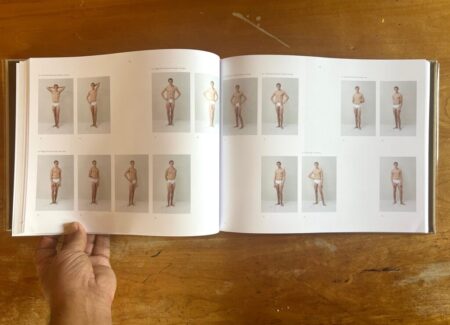

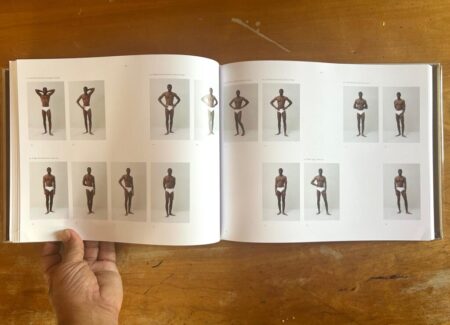

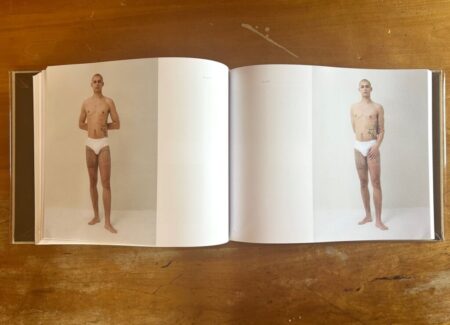

After dispensing with Nick, Ellis seeks out other men. Her casting call: “Find me twenty boys. Athletic. Abs. Good thighs.” Soon enough she finds willing subjects. The next 50+ pages are devoted to the results. Twenty handsome models appear in a sequence of gridded series, following the rough model of Nick’s prototype. All are young, fit, and expressionless. They are dressed in Nick’s underwear as well, but lacking his titillations. Instead the men are anonymous, impersonal, and labeled with cursory descriptions, e.g. wide legs, arms mix. “I didn’t want connection,” explains Ellis, “only obedience.” Yes, ma’am.

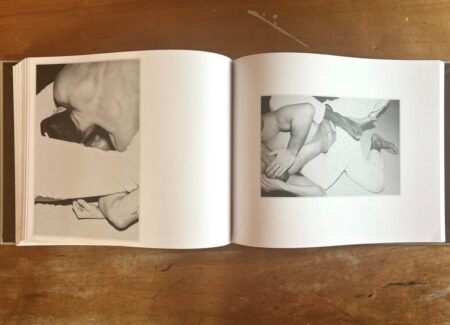

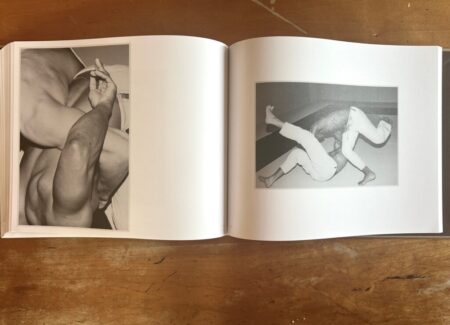

Ellis was on a mission. In these boyfriend casting calls, she churned through bodies and pictures like a termite through dry rot. Next up: the local martial arts gym, where she surrounded herself with fresh meat. “It was the bodies I wanted most,” she writes about the gym’s male members. “How they trained them, fed them, sculpted them.” Her third series captures men grappling and sparring. Their fates are bound together along with their bodies. Ellis crops their faces to focus on chests, limbs, and brute physicality. Photographed in black-and-white under harsh flash, these pictures have a passing resemblance to street candids, with an intriguing degree of detachment and happenstance.

“I was manic,” Ellis announces at this point. “Two years since Nick broke up and I hadn’t stopped—photographing, fucking, photographing.” Her twin urges had become interchangeable. The only direction was forward, but to what end? “Everything moved too fast to understand what I was doing,” she sighs.

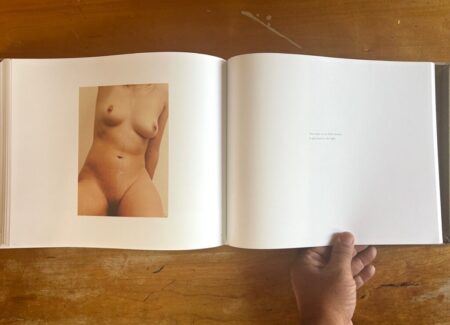

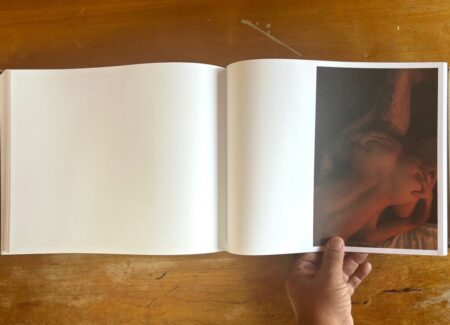

Before she can slow down, she meets Garth. He becomes a general subject in the next series, along with Ellis herself, as she documents their sexual relations. Perhaps this is some version or perversion of the male gaze? I’m not equipped to answer—nor can I tell how she accessed the shutter button in certain positions—but the photos are lascivious and explicit. So are the texts. “You came in my belly button,” she writes. “It glistened in the light.” It’s not clear exactly which image this refers to. There are a few possible candidates. Ellis throws her own classically framed torso into the mix for good measure. Once again sexual and photographic compulsions blend like bodily fluids. But there’s a deeper subtext this time around. “In trying to author the male image,” explains Jansen, “[Ellis] found she wanted, needed, to author her own image, too.” Perhaps Ellis is throwing a bone to photo history? Then again, she might be conducting self analysis. Maybe they are twin drives?

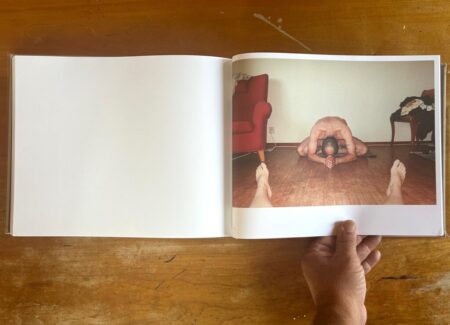

In any case, these couplings soon give way to singular images. Ellis closes out her book the way she began it, under the spell of a nude man. This time Garth has replaced Nick. Ellis consumes his tattooed body with her camera in a series of domestic tableaus. He is often cast in shadow, and viewed at a remove compared to Nick’s blunt proximity. Has she grown bored of Garth already? Perhaps, but never bored of photographing.

Ellis finishes Garth off with a groveling coda: In the last photo he lies prone before her in a lotus position, with his hands clasped on the floor in silent prayer. In the foreground we see the tops of her bare feet, lord of all she surveys. He is her plaything, ready to obey. It’s hard to imagine a more submissive image of manhood. The male gaze has been routed, her twin urges consummated. On that issue, The Boyfriend Casting leaves no doubt.

Collector’s POV: Rosie Harriet Ellis does not appear to have gallery representation at this time. Interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via her website (linked in the sidebar).