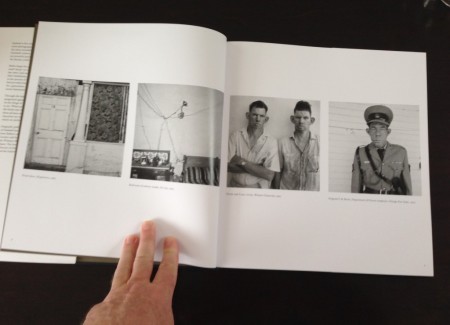

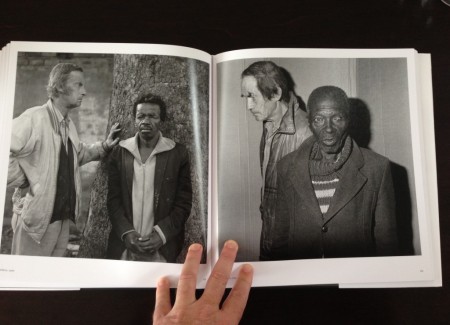

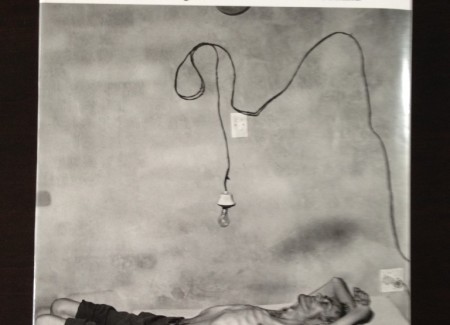

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2015 by Phaidon Press (here). Hardcover (10 1/8 inch square), 120 pages, with 91 black-and-white photographs (30 more than in original edition). This is the second and expanded edition of a book first published in 2001. Includes a preface by Peter Weiermaier and an essay by Elizabeth Sussman. $49.95. (Spread shots below.)

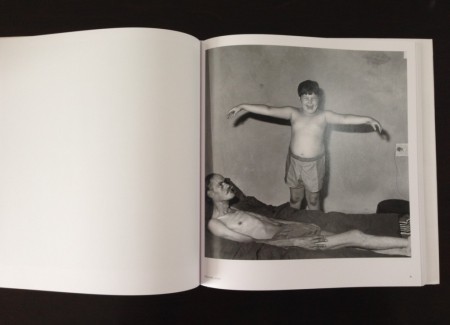

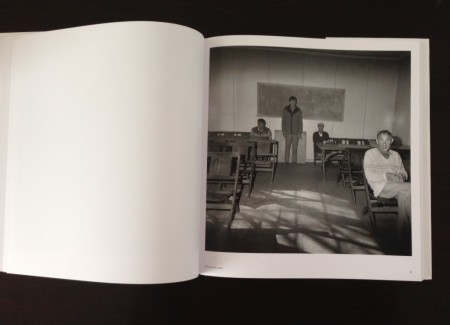

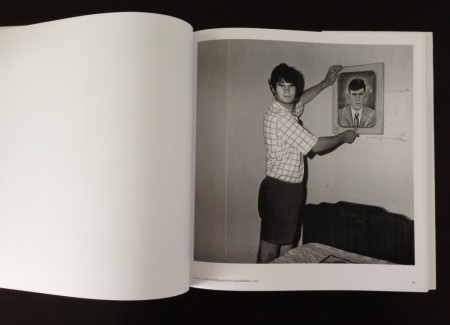

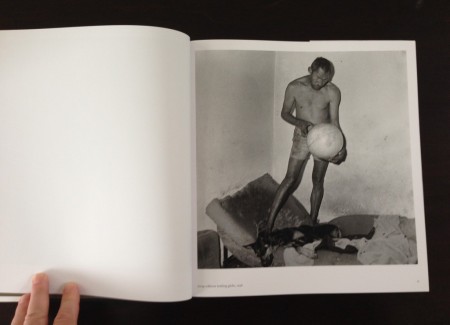

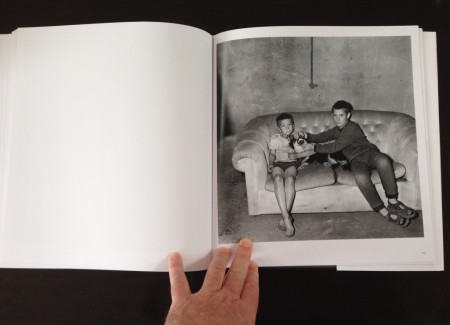

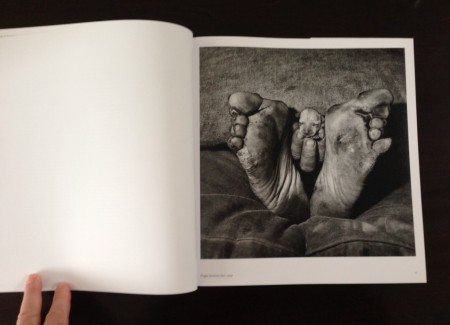

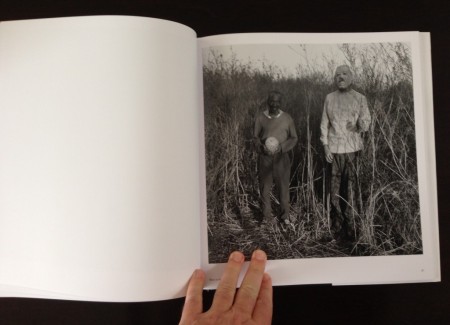

Comments/Context: Roger Ballen’s portraits of impoverished and deformed rural Afrikkaners tend to incite a pair of related responses. The first is one of shock and fascination. The people in these square photographs are like monsters on springs that have just popped out of a Jack-in-the-Box. They are fully aware of the camera and act up for Ballen—leering, scowling, holding up baby animals, wearing helmets of wire on their heads, goofing around. Many of the men are shirtless and almost all are unwashed. Studying their twisted postures and crazed eyes (when they have any), we can guess they’ve been damaged at birth or crippled by drugs, poverty, neglect, self-loathing, or social ostracization.

In this series, Ballen gives us the opportunity to meet people we haven’t seen before, and probably wouldn’t care to, except in photographs. We can view them safely from a distance, on the page or the walls of a gallery, and not have to worry about their unpredictable behavior were they seated at an adjoining table in a restaurant or standing behind us at a coffee stand.

Jaw-dropping wonder is almost immediately followed by a second response, one of withdrawal, anger, disgust, and ultimately by righteous condemnation. Who granted Ballen permission to photograph these people in this way and why does he think he should have that freedom? Do his subjects have any control over their self-presentation? Any clue that we might perceive them as freaks? Capturing their bizarre expressions in the glare of a flash gun, which he uses like a baton to keep them at a distance, he acts more like an animal trainer at a circus than a photographer looking at a fellow human being.

The tension between these conflicting responses has been familiar to audiences since the debut of Diane Arbus in 1967. Crowds flocked to her MoMA retrospective in 1971. Many (including Susan Sontag) were initially upset or enraged by her photographs of sideshow performers and mentally retarded children. The museum staff had to wipe spit off the protective glass left on the portraits at the end of the day.

Numerous other photographers have been brought up in the court of academic opinion on charges of exploitation. Over the decades critics have cited Walker Evans, Weegee, Eugene Meatyard, Richard Avedon, Andrea Modica, Eugene Richards, Shelby Lee Adams, Robert Mapplethorpe, Sally Mann, Tina Barney, Boris Mikhailov, Laurel Nakadate, Nikolay Bakharev, and Pieter Hugo for crimes or infractions. Each took photographs based on grossly unequal relationships, one in which the free-floating artist enjoyed all the power and the abject subjects had almost none.

It is never clear under what circumstances artists earn the right to depict the powerless, and in which style. The code is flexible. The rules are unwritten and, except in special cases, unenforceable. To my mind, Weegee and Arbus were supreme in balancing reportorial daring and gut-wrenching compassion. Adams and Ballen seem far less skillful at photographing misery and alienation with the requisite tact.

Their supporters might argue that, when faced with portrait subjects from the underclass, all artists have three choices: 1) to abstain from photographing such people, thus ensuring their invisible status in society and leaving us with no credible information about their condition; 2) to make well-mannered pictures that don’t highlight abnormalities and that vaguely dignify an outcast state; or 3) to do what Ballen and Mikhailov have done—engage subjects in a raucous collaboration that often leaves them appearing even more depraved than before.

Ballen’s settings are riskier than Arbus’s. His pictures suggest ugly acts of violence could erupt at any second. As a white South African, he also enters into the portrait negotiations with privileges that his black South African subjects don’t possess. The post-apartheid era has legally changed the status between ethnic groups. Socially and economically, especially in the case of the rural poor, improvements have been harder to see. There is no question who has the upper hand in these sessions.

But if these scenes should ever veer out of control–and he has written a few times about feeling threatened–that’s because he is a blunderer. He doesn’t seem to know what he is after other than scenes of depravity that he thinks will amuse himself and us. There is no discernible line between dangerous acts he wants to encourage and record, and those he might consider beyond the bounds of propriety. Arbus explored the margins of society while holding her camera in front of her like a moral compass. Ballen surrounds his bedraggled men and women and children with props—dogs and puppies, cats and kittens, white rats and their offspring, a dove, a pig, splices of wire, a gun—and then has them improvise. He sets them against walls on which they have drawn words or cartoons. It’s an insane asylum where he is the set decorator and director.

It is strange (and disappointing) that neither of the essays by Peter Weiermaier or Elisabeth Sussman raise the issue of exploitation in Ballen’s work, as if that word were an impolite or loaded term. They never examine the thorny ethical problems that should stand in the way of anyone wholly endorsing Ballen’s techniques. Instead, the authors compare Ballen with Samuel Beckett and locate his work within the theatre of the absurd, analogies that are grotesquely inadequate and misleading. These South African misfortunates are not actors and the squalid rooms they inhabit are not a stage set, even if Roger Ballen and his enablers want to pretend he is merely an existential entertainer. To treat material this sensitive and explosive from the real world he needs to show a surer hand and eye than he has so far demonstrated. These are photographs by a moral oaf.

Collector’s POV: Roger Ballen is represented by Robert Koch Gallery in San Francisco (here), Hamiltons Gallery in London (here), and Galerie Karsten Greve in Paris (here), among others. Ballen’s work has been only intermittently available in the secondary markets in the past few years, where prices have generally ranged between $2000 and $25000.