JTF (just the facts): A total of 20 photographic works, framed or framed/matted, and hung against artist-designed wooden armatures and white walls in the main gallery space and the back gallery area. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 3 acrylic and toner on canvas, 2025, sized 36×44, 36×45 inches, unique

- 8 acrylic and toner on canvas, 2025, sized 60×48, 48×60 inches, unique

- 1 acrylic and toner on canvas, 2025, sized 88×60 inches, unique

- 8 gelatin silver prints, 2025, sized 20×24, 24×20 inches, in editions of 3+1AP

Comments/Context: The emptiness of desert landscapes, both in the United States and around the world, has long provided artists with seductively wide-ranging inspiration. Land and Earth artists have seen the imaginative possibilities in such massive open unpopulated spaces, creating installations that react to and interrupt the natural conditions, while photographers have meticulously investigated the harshly beautiful but unforgiving environments, documenting both the dreams and aspirations of those who attempt to build lives there and the remnants of those who have long since gone.

Rodrigo Valenzuela’s recent projects step into the varied aesthetics of this desert environment, using the Atacama Desert in his native Chile as his visual starting point. Valenzuela has been consistently busy in the past decade, with a string of gallery shows in 2018 (here), 2019 (here), 2020 (here), and 2022 (here) matched by a 2021 Guggenheim Fellowship and a teaching position in the photography department at UCLA. During that time, much of his work has centered on studio-based constructions which he has made to be photographed, with successive explorations of found building materials, hard edged geometries, machined agglomerations, and more organic sculptural forms, each with its own resonances. In his newest works, Valenzuela moves back outside, with two complementary projects that consider the desert world in sculptural ways.

While this gallery space is relatively long and narrow, Valenzuela has broken up its regular flow with constructions of wooden 2x4s that jut out from the walls and provide locations to hang his new works, on both the front and the back. The resulting progression through the room is rhythmic – a look, a turn, a look, and movement to the side, a look, a turn, and so forth – wandering from front to back in the space. Valenzuela has often used everyday construction materials like 2x4s in his work previously, so this rethinking of the spatial dynamics of the gallery feels like a natural extension of that interest in building, framing, and redefining.

The large works from Valenzuela’s series “New Land” begin with medium format images of the desert, particularly the area called the Valley of the Moon, with its desolate landscapes. Made on foot during long walks through the region, the pictures feature expansive views of empty desert, punctuated by scrub in the foreground, mountains in the back, and cloud-dotted skies overhead. Valenzuela’s process then involves multiple layers of printing, with certain areas of the images added or subtracted in geometric shapes, creating veiled areas of light and dark, like planes defined by receding lines of perspective. The resulting compositions (reminiscent of some of Grey Crawford’s landscape interventions from the 1970s and 1980s) combine the open landscapes with imaginary architectures, each scene redefined by the layered intersection of repetitive forms and divisions that might be walls, windows, and other built structures. To this he then adds overpainted lines in black, white, and yellow, further emphasizing the edges and facets of these forms, almost like the bold aesthetics of Constructivism.

Given Valenzuela’s previous interest in construction, it’s hard not to see energetic architectural intervention in these pictures, even if it is dream-like or imaginary. Shadowy planes break up the open space, defining edges and creating organization amid the dust and sky. Many of his compositions have an implied sense of movement (just like that in the gallery space), with planes alternating back and forth, criss-crossing, and intersecting, with an almost musical structure. Each resulting work feels like an aspirational plan, the vacant desert now inhabited by futuristically hopeful almost-buildings and optimistically sketched ideas.

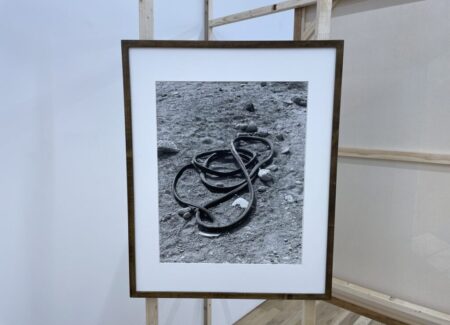

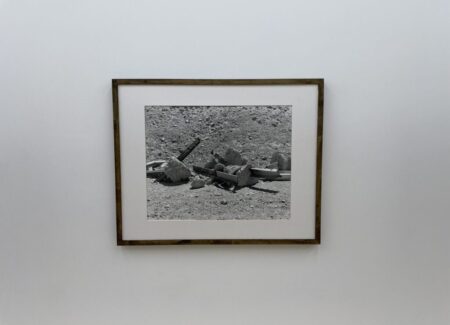

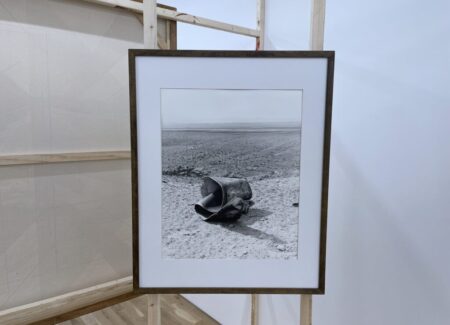

Intermingled with these desert visions are a series of more traditional black-and-white photographs of objects found in the desert (“Los restos” or the remains). These images follow in the aesthetic footsteps of photographers like Lewis Baltz (particularly his 1978 portfolio “Nevada”), whose works documented the leftover detritus of American expansion. Valenzuela’s pictures are equally sober in their vantage point, but his prints are lushly refined, creating even more tension between ugliness and beauty. A pane of broken glass shatters atop the rocky ground, creating an interplay of shapes and reflections (with a nod to Robert Smithson.) A discarded rubber hose twists in lovely sinuous curves amid the rocks and stones, like a snake. A burnt out bus carcass shows off its blackened structural ribs, like weathered bones left to bake in the sun. And other less identifiable finds, like concrete blocks, twists of metal, and steel girders, become the visual raw material for Valenzuela’s sculptural eye, each discarded object seen anew in the context of the severe desert.

When these two projects are interleaved, as they are here, an oscillating effect is created, between aspiration and gritty reality – Valenzuela finds room for both in the desert, without resorting to overly easy opposition. What we’re left with a sense of uneasy coexistence, of the desert never really paying much heed to any human intervention. Valenzuela offers us glorious dreams of modernity amid the majestically echoing emptiness, but tempers that hope with a few reminders of time being reclaimed by the disinterested and unforgiving land. It’s this subtle pressure that gives this show its bite, the structural balanced by the natural in a never ending tussle.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced as follows. The acrylic and toner works range from $8000 to $22000 each, based on size, while the gelatin silver prints are $4000 each. Valenzuela’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.