JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by Art Paper Editions (here). Hardcover (21.5×29 cm), 120 pages, with 70 black and white and color photographs. Includes an essay by Brad Feuerhelm. In an edition of 1000 copies. Edited by Jurgen Maelfeyt and Rita Lino, and designed by Jurgen Maelfeyt. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: The work of the Portuguese photographer Rita Lino has always been about self-portraiture and self-analysis. Originally she started taking self-portraits simply because there were no people around her to photograph; her friends didn’t want to pose the way she wanted them to. So she started working on self-exploration, researching photography, poses, and the body. In her earlier photobook Entartete (reviewed here), Lino embraced sexuality and an almost fearless sense of self-analysis, exploring the relationship with her body in a playful, blatantly honest way. Lino’s new photobook, titled Replica, also focuses on self-portraits, yet it is more conceptually-driven and less autobiographical.

It took Lino about four years to put this body of work into book form. As she was gathering the series together, the writer and curator Brad Feuerhelm recommended taking a look at the work of American photographer William Mortensen, and in particular Mortensen’s ideas for how to pose a model. Mortensen’s recommendations were documented in the book “The Model: A Book on the Problems of Posing” (1946), and in his view, the model’s emotionality is “irrelevant and misleading” and the model is simply a “machine that needs adjustment”. Lino worked with Feuerhelm on a text that would read similar to Mortensen’s, but go a step further. Together, they reviewed the main chapters of Mortensen’s book, and recreated the key focus of each one. The resulting text, placed throughout the book, became essential to Lino’s visual narrative.

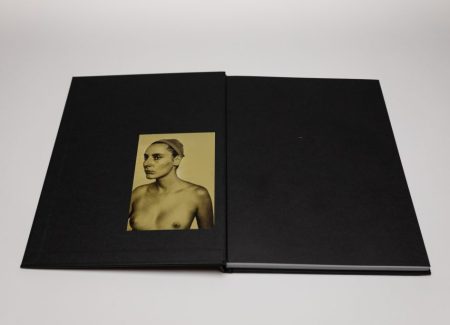

Replica is a hardcover book of a comfortable medium size. A photograph of the artist, shot from the back as a cast of her head is being taken, appears on the cover in silver. It immediately signals a project focused on inward-looking photographic study. The artist’s name, the title, and the publisher are elegantly placed on the spine in silver font, and inside, the photographs are mostly black and white, with their size and placement on pages varied throughout the book.

The first image in Replica appears glued right on the end papers – a medium size portrait in sepia shows the artist as she looks to the side, her head covered with a mesh cap. Perhaps here Lino is sharing her self-portrait, before the actual photographic study begins. In the photographs that follow, she consistently removes herself (as a person) from the imagery and reduces her body to a more abstract representation.

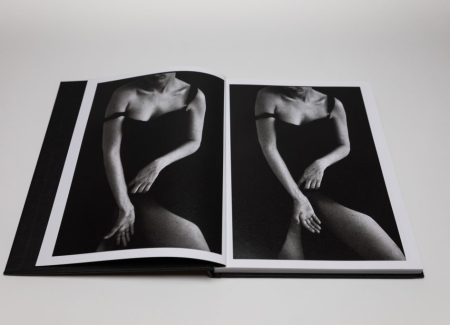

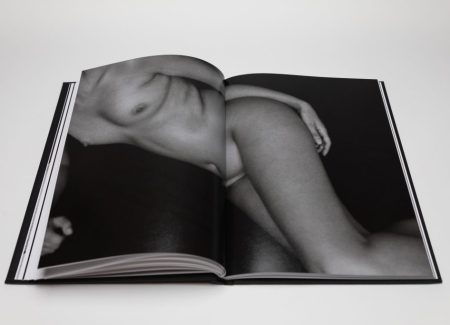

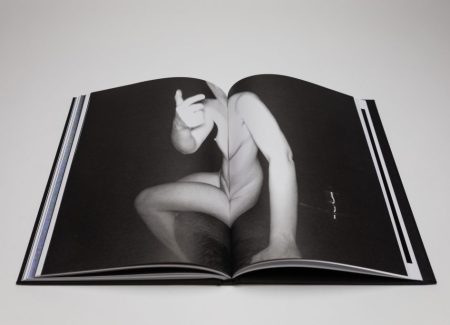

Replica suggests a new reading of the body, as Lino takes on multiple roles at the same time: she is the model and the photographer, and also the subject and the image. Her self-portraiture is controlled, and her body functions almost in a machine-like manner. “It became not so much my body but a body”, she said, placing the restrictions articulated by Mortensen at the center of her work.

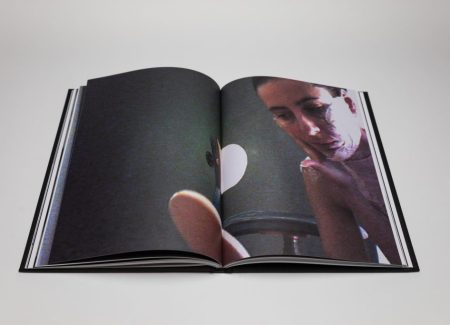

“This short guide consists of a series of suggestions for considering the posing of the human model in the modern age” reads the beginning of Mortensen’s manual. The very first suggestion instructs the artist “To Increase or Decrease Emotion in the Face”. Then, the book opens to a fold out with four images showing the artist as she applies plaster to her face in first photo, sits in a chair with half of her face and neck covered in the next, poses standing with her entire face covered in the third, and places herself on her knees with her head out of the frame in the last. The camera trigger is seen in her hand, making it clear that she controls all of this activity.

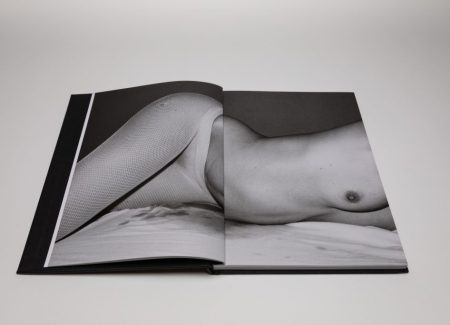

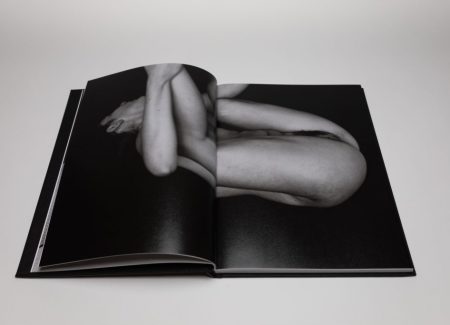

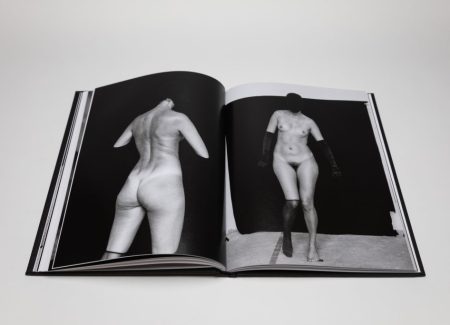

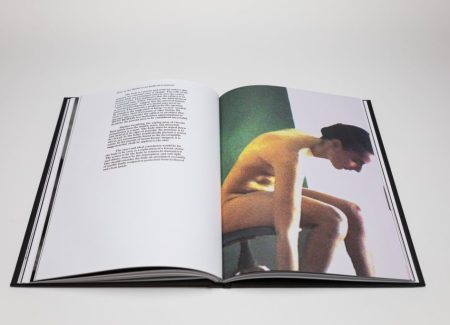

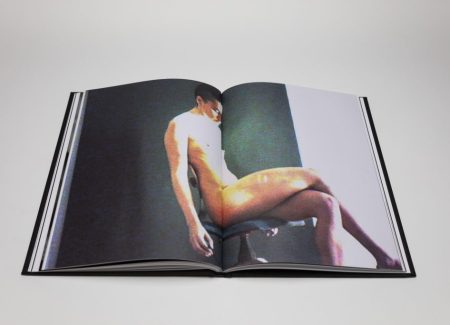

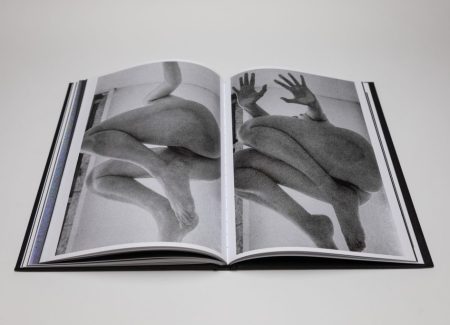

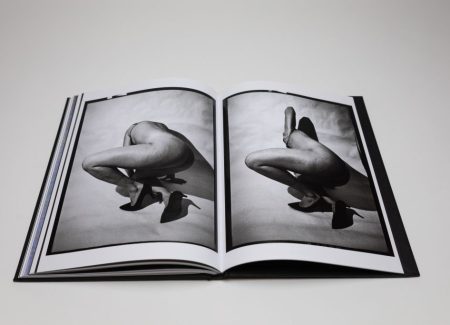

Another instruction is titled “Posing the Model as If Observed in Secret”, and suggests that the model is “unaware of their observation”, “there may be obstacles between the model and the operator”, and “the sitter may also be given the shutter release cable”. The images that follow capture Lino’s nude body from under glass she lies or stands on, while in another shot, she poses nude on a block. Here again, Lino seems to take the suggestion to its extreme.

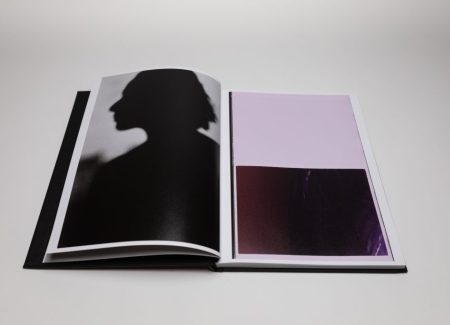

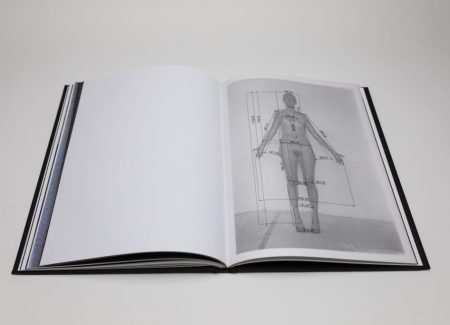

Mortensen was particularly specific about the arrangement of the hair, stating that it belongs to the “problems of physical adjustment”, and “must conform to and develop the anatomical structure of the head”. Lino’s response is a black and white image of the artist’s shaved head, overlaid with transparency paper marked with measurements, pushing this recommendation to another level. In other photos, Lino poses with her limbs and head covered in black fabric making them blend in with a black background, creating the effect of an armless statue. A spread with a contact sheet shows the steps, again making it clear that the artist controls the process.

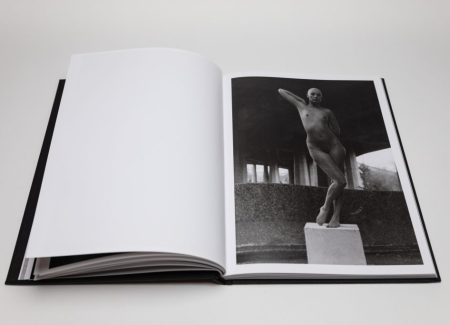

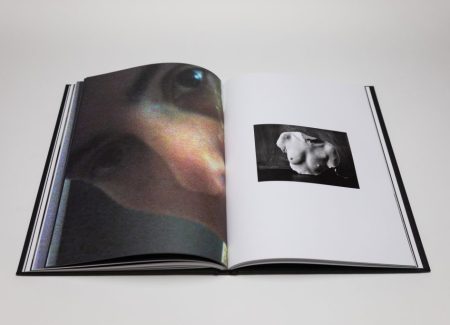

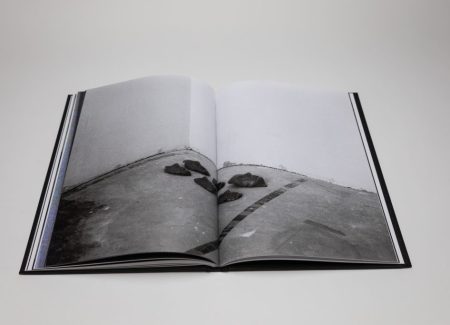

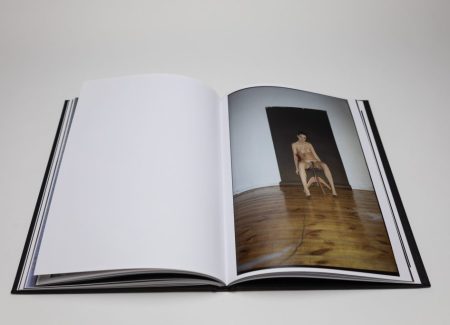

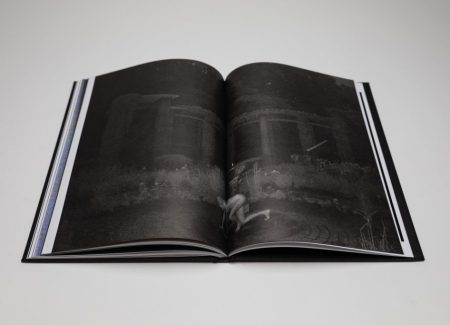

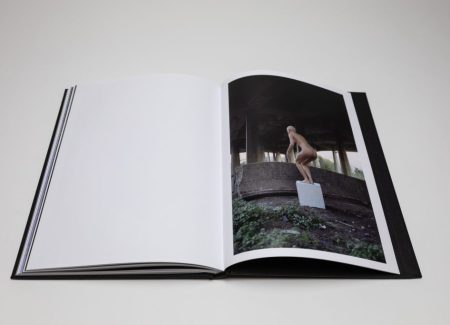

The final chapter suggests to “pose the model as an artificial construct”, as the body “remains in a constant change”. It states that ideally it should be close to a “replication of a Greek statue”. A sequence of blurry low-res images depicts Lino moving around with a chair. The final spread pairs an extreme close up of her face with a small black and white image of a sculpture of her upper torso and head. Lino’s photographs are very clinical and technical, photographed with precision, stripped of any emotion or individuality. The book ends with a color photograph of Lino standing nude on a white block, her legs are slightly bent, and she is turned to a slight degree. Ultimately, she removes her personality and identity from the image making process, letting her body become an anonymous object.

A number of notable contemporary female photographers continue to explore and reclaim the female body, often using self-portraits to challenge stereotypes and offer alternatives to the male gaze. Talia Chetrit shares her vulnerability through expressive visual portraits in Showcaller (reviewed here); the Japanese photographer Mari Katayama uses self-portraits to talk about her disabilities in her photobook Gift (reviewed here); and Finnish artist Elina Brotherus is known for her melancholic self-portraits, often charged with complex personal and emotional experiences. Lino’s work is an excellent contribution to this conversation.

Lino says that the book “came out of the process of creation, the need to explore and the notion of always being curious, where the ride is more important than the destination”. Lino appears in full control, making it clear that she understands her roles both in front of and behind the camera. Replica is evidence of the artist’s ongoing maturation and evolution, challenging herself to explore and photograph her own body in new ways.

Collector’s POV: Rita Lino does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result collectors interested in following up should likely connect directly with the artist via her website (linked in the sidebar).