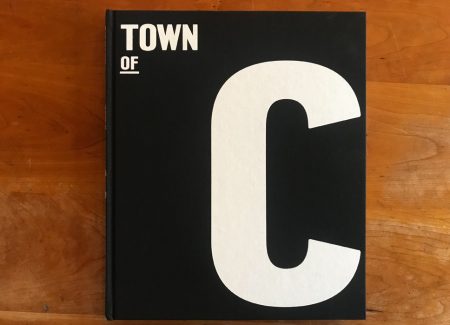

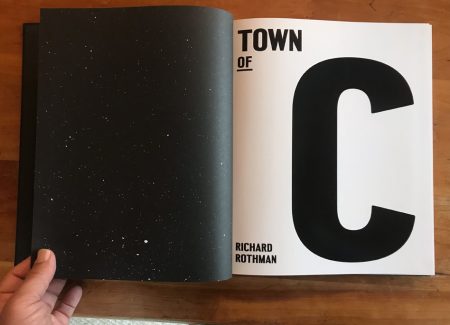

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by Stanley/Barker (here). Clothbound hardback (300 x 250mm), foil stamped, with tipped in rear cover photograph. 164 pages, with 82 monochrome photographs. Design by The Entente. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Richard Rothman, 65, lives and works in New York, but he is perhaps best known of a body of work shot 3,000 miles away in Northern California. His 2011 monograph Redwood Saw focused on Crescent City, a small coastal town near the Oregon border whose best days were behind it. After several boom-bust extractive cycles, the primary employer was a maximum security prison. Rothman’s portrayal mixed natural scenery, social landscape, and portraiture, including several jarring nudes. They joined into a bleak document of the community. If the photos left some wiggle room, the text made Rothman’s opinion clear. “Crescent City is a very unhealthy town,” he wrote. His open condescension earned some detractors. But the book’s visual strength was undeniable. The flow of place, structure, and residents laid bare was deceptively seamless, and Nazraeli’s topnotch production boosted it into something of a minor classic.

As it turns out, Redwood Saw was not Rothman’s only western photo venture. While working on that series, he was engaged concurrently on another project. This one was focused on Cañon City, a town at the base of Colorado’s Front Range, roughly 2 hours south of Denver. It too had been through the boom-bust wringer, and now relied on a nearby prison as an economic base. Among the town’s 17,000 residents was his wife’s extended family. She had grown up there and could trace her roots to the town’s original settlers. He imagined they might make good portrait subjects, and perhaps provide entrée to the broader community. Perhaps it might develop into a snapshot of one small town, or western ideals, or continental divides? The possibilities were open. He began to shoot there in 2004, coinciding with family visits, around the same time that Redwood Saw was ramping up.

As with many long-term photo projects, this one didn’t go quite as planned. Rothman and his wife divorced mid-way through. Her family withdrew from participating. Rothman was undeterred. Already well into it by this time, he adjusted course and moved ahead. The resulting book Town of C was recently published by Stanley/Barker. The generic title refers to universal themes, but its facts on the ground are quite specific. Although this book comes ten years after Redwood Saw, it is something of a sister book to that title, with notable parallels and some key differences.

Right off the bat, the book distinguishes itself with unconventional design features. The cover includes traditional information: title, author, and tipped in photo. But the front type is skewed out of scale, and the placement of graphics reversed, with the author and image appearing on the back cover. The endpaper pattern is a pitch black starry sky, followed by a preface which weaves through several pages, interspersing photographs with text blurbs before the main body begins in earnest. Stanley/Barker has toyed with these ideas in other books —for example, in the printed endpapers and reversed cover of Headed West, (reviewed here) and the sporadic text introducing The White Sky (reviewed here). It’s nice to see a publisher experiment with conventional wisdom. With Town of C, they have pushed the boundary slightly further. Once expectations have been scrambled, the combination of bland title and celestial void can sweep in as a palate cleanser. The open frontier awaits.

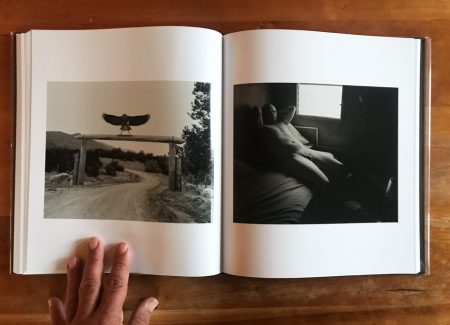

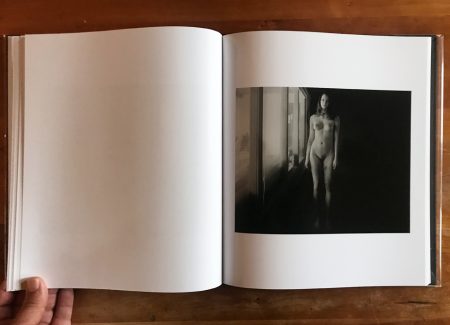

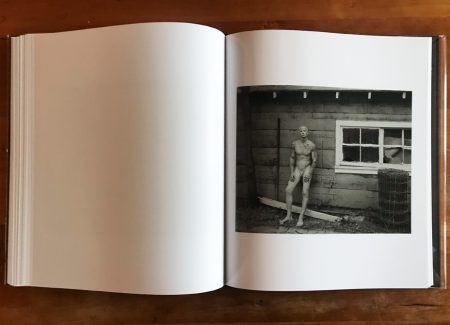

The initial photograph settles on a nude couple embracing in a prison cemetery. The man is maybe twice the woman’s age. They loom like biblical figures in the center of the frame, peering back impassively at Rothman. This is the first of several nudes which appear as a recurring motif, all with similar composition and emotional tone. They pick up the trail laid down first in Redwood Saw, where nude studies nestled uncomfortably amid a mix of redwoods, fast food, and churches. Rothman explained them then as a way to “up the ante.” “How can I make this richer, more difficult, more challenging, more rewarding?” he asked himself. Nudes checked all the boxes, at least in Redwood Saw. Its successor is a different book. Some of the initial shock value has worn off, along with past remnants of small town naïveté. “I wanted to bring the spirit of Eros into the work,” he wrote ten years ago. If Redwood Saw did not consummate that desire, Town of C comes closer. The nude subjects here are variously fit, shaved, tattooed, and implanted for sex appeal. I could be wrong but I suspect this is not their first time stripping before a camera. The vulnerabilities here may not be just naked expositions, but thematic pretensions.

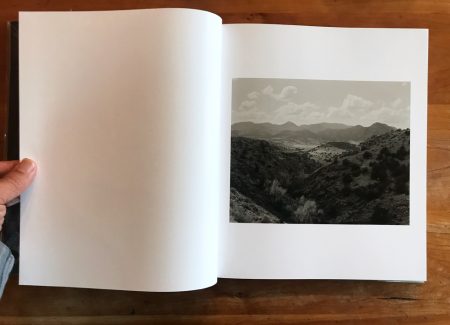

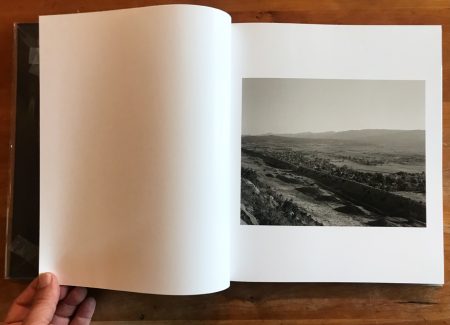

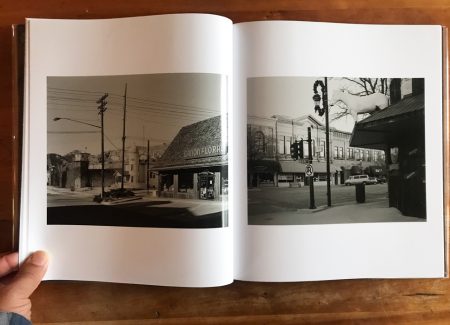

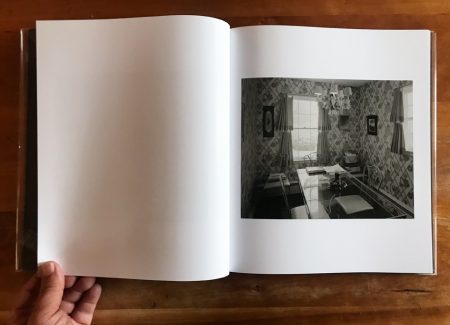

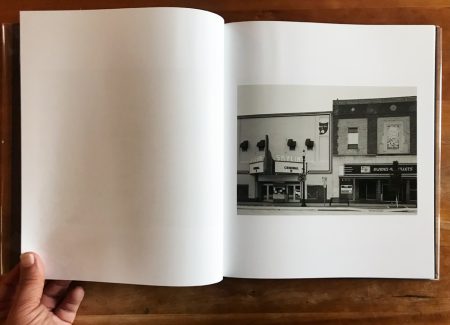

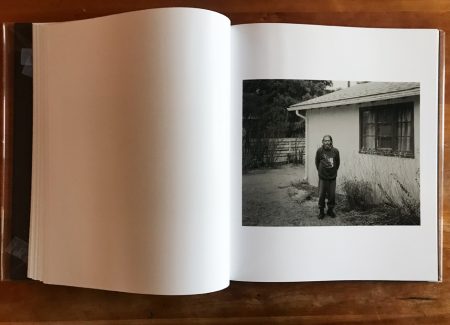

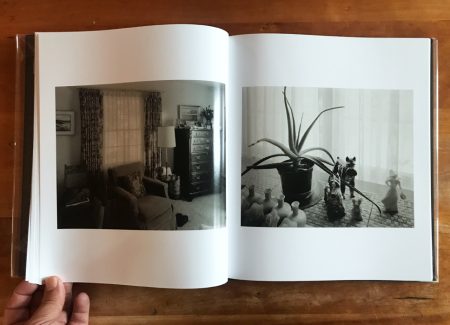

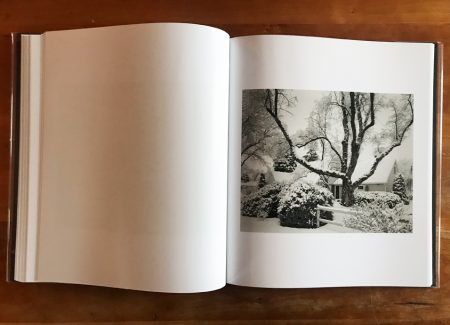

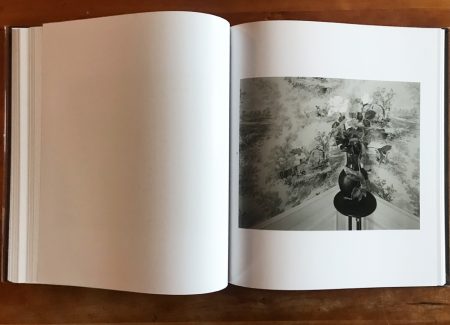

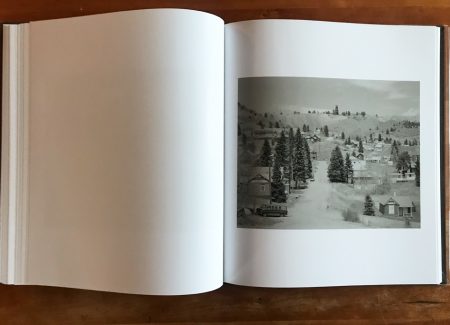

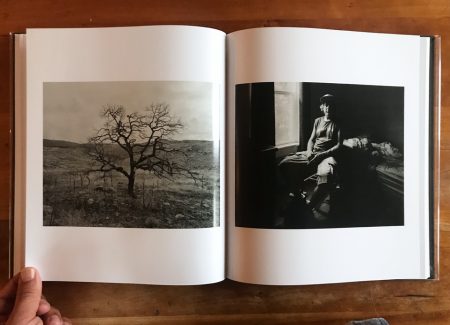

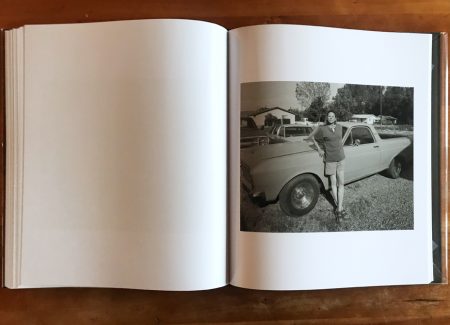

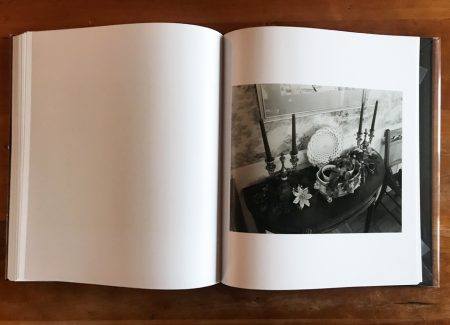

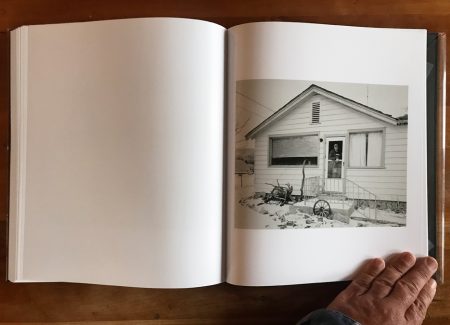

A short series of mountain vistas follows the pair, setting the geographic scene. It’s hard to imagine a more idyllic alpine setting. Then it’s quickly into Cañon City proper, with a sequence of photos introducing Main Street, a residential overview, a commercial lot, and a stroll near middle class homes. Everything seems in order. We might be viewing an Andy Griffith set from the sixties, a sense soon reinforced by an interior shot of a dining room with wallpaper, furniture, and curtains seemingly frozen in time.

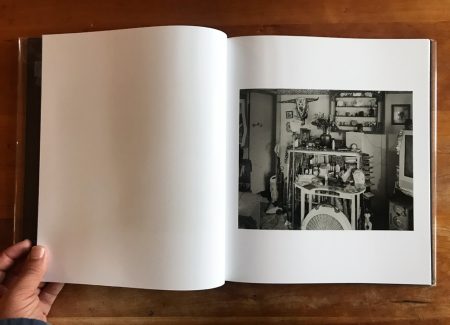

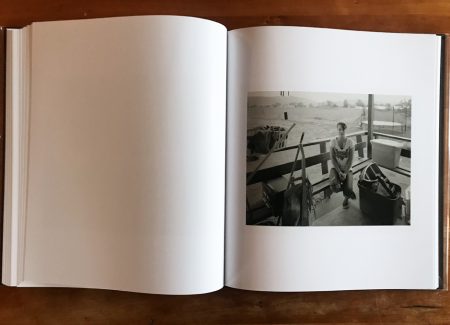

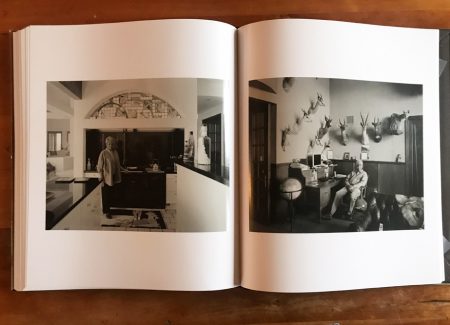

This is the first of several interior photos in the book. Taken collectively they mark a left turn from Redwood Saw. Rothman kept that subject at arms length, always pausing at the entrance, and observing exteriors with cold remove. Town of C seems a deliberate attempt to inject himself into his pictures. To be sure, he remains passive, watching silently from the wings. It is still hard to determine his relationships or exact standing. But this time, by whatever the means, he has conjured the delicate photographer’s trick of access. Photographs of a living room with Christmas tree, a man puttering around the back patio, a bedroom, dining table, and toy strewn nursery fill out a mental image of mundane domesticity. Interior shots of a napping mom with child, and a boy sprawled asleep on his bed feel intimate and personal. A sequence of portraits of one girl, shot on back porches over the course of several years into teendom, lends a tone of familiarity. They are paced several pages apart in the sequence, through shifting ages, clothes, and backgrounds. The book does not identify her but she clearly she has some relationship with Rothman. Her continued reprisal signals the long-term nature of the project, and hints at his repeat visits.

Even Rothman’s nudes take on a familiar ambience. In Redwood Saw, these were always in the open air, with the somewhat stiff and distant tone of fleeting transactions. Town of C moves the setting indoors for several, with available light keeping a tenuous bond to the outside. Soft shadows fall across bare skins of a woman straddling the entrance to a dingy mudroom, a man leaning into a plywood corner, and Barbie-like figure by a window. Several clothed subjects appear in similar environs: a man engaged in fireside meditation, for example, or a Motörhead fan in his dark bedroom. Rothman has captured them all in places of comfort, perhaps taking a step toward outright friendship. Nevertheless, his exact relationships remain indeterminate, and the photos somewhat unresolved.

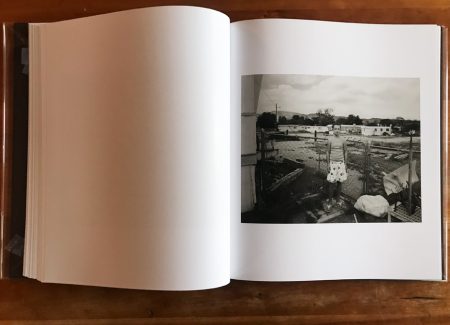

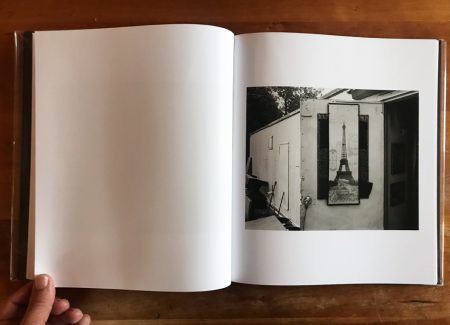

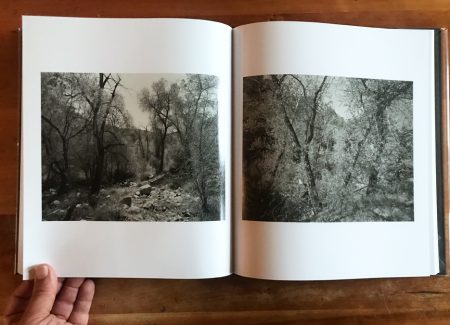

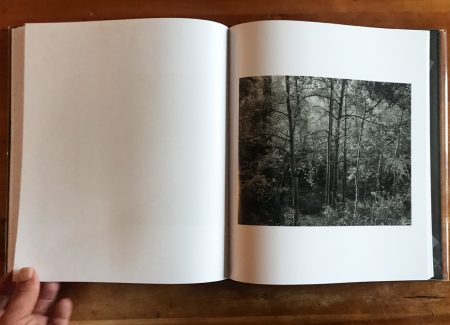

The same sentiment might apply to Cañon City as a whole. Rothman’s sequence is lively, bouncing between portraits, structures, greenery, interiors, and back again, never lingering for long in any area. Each one is represented in roughly equal measure, and by book’s end they’ve captured Cañon City inside and out. But Town of C’s lyric documentary never settles into firm opinion. Instead it picks around the edges. Pictures of a dirt road leading into an arid hillside, a downtown theater, or fresh snow on a yard are gorgeous. Rothman has a keen sense of natural space. His photos unveil terrain with the precision of 4 x 5 and decades of practice. Reproduced here in high fidelity, they provide countless details for discovery. But they feel more like facts than family. The book’s title is deliberately impersonal. It extends Cañon City’s reach to other places. But the effect is to intellectualize, like a scientist applying a Latin label to a bug in amber. Nowhere in the book or publisher site does the actual town name appear.

Rothman’s interloper perspective may be baked into the equation. No matter the length of his stay, he was always a temporary visitor, shooting in a flurry before inevitably leaving again. In a small community built on long-term bonds and rhythms, such a division looms larger than in New York. When Rothman earned a Guggenheim in 2015, the gulf to small town America might have widened. The following year, Trump’s election solidified it into a true chasm. The last photograph in the book was made in 2016.

Rothman seems to embrace outsider status in the last several photographs. Beginning with a lonely dirt road receding to the horizon—a photo cliché, yes, but suitable here— the sequence captures snippets of the high mountain scenery near Cañon City. The vantage tilts up in the last two photographs, so that sky and clouds dominate the frame. Its a subtle reprisal of poses we’ve seen earlier, with several subjects flat on their backs or with upturned faces. The last photo is the starry night photo quoted in the end papers. By this point the photographs are entirely removed from the town, removed in fact from the planet’s surface. The phrase “flyover country” has been elevated into orbit. The coda is reminiscent of Redwood Saw, which also left civilization behind to close with a short series of oceanscapes. Both books affirm that any departure carries emotional weight. That’s true for clouds, sea, or people, whether remaining in a place for decades, or just passing through.

Collector’s POV: Richard Rothman does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).