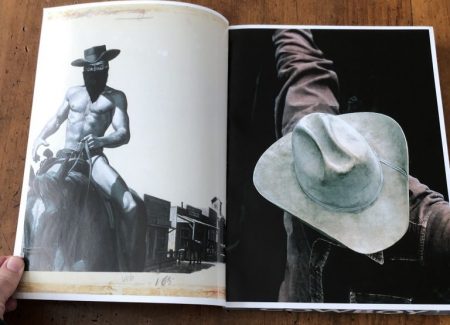

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2020 by Prestel Publishing (here). Paperback, 484 pages, with 573 color and 173 black and white illustrations. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Richard Prince was born in 1949 and so has witnessed the sharp ups and downs in popularity of the Western. It was already beginning to wane as a movie staple in U.S. theaters during his boyhood; its heyday had been the late-1930s through the mid-1950s when John Ford was in his prime. The apex of its prestige in Hollywood was the 1950s, when High Noon (1952), Shane (1950), and The Searchers (1956) garnered high-toned critical praise and—a rarity—recognition from the Academy of Motion Pictures. Almost simultaneously, however, the western was coopted by television where it burrowed deeply into the home. Gunsmoke (set in Dodge City and overseen by the strapping marshall Matt Dillon) became the top TV show in America from 1957-1961 until it was displaced by Bonanza, the #1 show from 1964-67. (That 8 of the 10 most watched TV shows in the ‘60s were Westerns is a stubborn fact that historians have yet to reconcile with the standard view of that “revolutionary” decade.)

Prince would have been in his early twenties during the mid-60s when Italian movie directors Sergio Leone and Sergio Corbucci revived the Western for hipster Europeans and Americans, launching Clint Eastwood as a movie star after his stint in the TV Western Rawhide—a period evoked last year in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood. (In a notorious legal imbroglio that Prince must know something about, the Italians borrowed without credit from the Japanese and got into trouble for it. As a result of acknowledging that his Fistful of Dollars (1964) was a rip-off of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961), Leone had to relinquish the Asian rights and 15% of international royalties to the Japanese director.) The avant-garde Westerns of Sam Peckinpah, The Wild Bunch (1968) and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), added further respectability to the genre.

But by the time Prince was making his first cowboy re-photographs (1980-84), the Western had disappeared from American television and movie screens. The financial disaster of Heaven’s Gate (1980) had killed it off in the minds of executives at the major studios. Most of the Western stars from the ‘50s (Gary Cooper, Randolph Scott, Lee Van Cleef) were either dead or inactive. John Wayne had been a hated target of the counter-culture since the ‘60s for his right-wing politics and remained a pariah despite Joan Didion’s affectionate attempt to salvage his reputation. Cormac McCarthy’s apocalyptic Western, Blood Meridian (1986), now widely regarded as one of the great novels of the 20th century, was read at the time by almost no one. The marketing behind movies such as Silverado (1985) and Young Guns (1988) stressed that the producers, directors, and actors were offering a revisionist take on an honorable form that the college-educated public regarded as moribund, reactionary, and irrelevant. Only the directorial vision and lean budgets of Eastwood kept Westerns alive, a faith rewarded when Unforgiven (1992) won the Oscar for Best Picture.

The one constantly visible Western icon during Prince’s adolescence and adulthood was the Marlboro Man. In 1954, the image of the cowboy on the open range was chosen by the Leo Burnett Agency as the focus of an ad campaign and, with minor tweaks, this masculine loner appeared on TV, billboards, store displays, and especially in magazines until his retirement in 1999. The longevity of the Marlboro Man, both domestically and internationally, and its success as a marketing vehicle, is unrivaled in the annals of advertising. In his opening essay to the catalog, “Way Out West: On the Frontiers of Appropriation with Richard Prince,” Robert M. Rubin notes that by 1972 Marlboro was the most popular cigarette brand in the world—thanks to the cowboy and his terse slogan (“where the flavor is”)—and it still is.

The model for the first Marlboro Man was an actual cowboy named Clarence Hailey Young. A photograph by Leonard McCombe of his weathered face and Stetson, tightly cropped, had branded the cover of Life on August 22, 1949. Years later, Burnett saw (or remembered) the photo, which shows Young staring into the distance, a cigarette between his lips, and oversaw a series of ads featuring a solitary, rugged figure in a cowboy hat atop a horse, riding around vast unpopulated Western landscapes. Prince has—perhaps only half-seriously—identified how his own life has intersected with these images by noting in a 2015 Instagram post that the date of Life‘s publication was “16 days after I was born.”

A fateful, hands-on encounter took place in the mid-‘70s when Prince got a job in Life’s cutting department that required him to tear out stories from old issues. What was left after the vivisection were the ads. As he began to photograph these photographs—of cigarettes, pens, watches, hands holding cigarettes—the compositions were, in Rubin’s words, “more Kazimir Malevich than Marlboro.” They had no resonance. Only when he began to re-photograph the cowboys in the Marlboro, entering the badlands of Western mythology, did Prince strike gold.

Rubin’s impressive catalog has two main purposes. The first is to demonstrate the ubiquity of Western tropes in American life and the many weird pathways they have taken. The book intersperses examples of Prince’s work over four decades with a myriad of quotes from authors across the literary spectrum: pulp writers (Eugene Cunningham); canonical novelists (McCarthy, Larry McMurtry, Annie Proulx, Jim Harrison, Barry Gifford, Sherman Alexie, Oakley Hall, and the late Charles Portis); cultural critics and journalists (Didion, Robert Warshow, Geoffrey O’Brien, J. Hoberman, Nick Tosches.)

He includes Prince’s Instagram shots of American icons in cowboy hats (Bob Dylan, J Hus, Barack Obama, James Turrell); screenplay excerpts from Westerns (David Webb People’s script for what became Unforgiven; Walon Green’s for The Wild Bunch; the last page of The Searchers); cover illustrations from paperback Westerns; and lyrics for cowboy songs by C&W writers such as Marty Robbins.

“It’s reductive to describe Prince’s work as a taxonomy of subcultures,” asserts Rubin. “It’s a taxonomy of America.”

Part of the fun for the reader is sensing what a blast it is for Rubin to display his erudition. He and Prince are both students of Americana, amateur sleuths who enjoy running down obscure leads and proposing connections between, say, the cowboy’s impact on gay culture, on American soldiers during the Vietnam War, on outlaw bikers, on songs and movies, and on presidential politics. The editing is less haphazard than a flip through would suggest. For example, by reproducing a Prince Instagram photo of Ford Mustangs fresh off an assembly line and arrayed in a parking lot, Rubin slyly (without text) aligns the cowboys with Prince’s car hood sculptures. (The book design is by Nicole Jedinak and COMA, whose layouts are as intricate and allusive as those found in an earlier Prince-Rubin collaboration, American Prayer (2011). Despite its girth and density, the catalog is a pleasure to handle and easy to use.)

Rubin’s second purpose is to absolve Prince of any artistic felonies or misdemeanors for reproducing the images of others without permission. “If Prince is a thief, his is a victimless crime—at worst, petty larceny, like taking soap home from a motel,” writes Rubin. “Not the bathrobe, mind you, just the toiletries. Who’s the injured party here? Philip Morris? Public domain may be a legal term, but for Prince it’s just what’s out there.”

To support his case that any controversy about appropriation is silly, Rubin reproduces an Instagram photo by Prince of a man on a bucking horse at Madison Square Garden in 2015. It bears the artist’s caption: “TOOK IT MYSELF. Big fucking deal.”

The abundant testimony of quoted and reproduced material in the catalog serves to buttress Rubin’s exculpatory verdict: by presenting just a tiny sample of the images and words about the West that we have been exposed to as Americans during the 20th century, he wants to prove how much is out there. Like the air we breathe, the myth of the West circulates deep in our brain, and it got there because we appropriated it from thousands of sources without thinking too hard about their origins.

That pictures are made out of pictures, however, is a given and beside the point. The audacity of Prince’s appropriations was not the act itself. After all, artists had been repurposing printed matter made by others and collaging it since at least the Victorian era. The brazenness derived from his means: Prince not only re-photographed cigarette ads, about as “low,” politically reviled, and commercialized a subject as one could imagine, but he also refused to disguise the pilfering or to pretend that he needed any photographic talent whatsoever to commit the robbery. He left intact the rips in the tear sheets and let us see the murky grain that resulted from blowing up a magazine photo taken with a 35 mm.

Prince described his process in a 2003 interview for Artforum. “I had limited technical skills regarding the camera. Actually I had no skills. I played the camera. I used a cheap commercial lab to blow up the pictures. I made editions of two. I never went into a darkroom.” Like certain punk and new wave musicians at the time who were proud to show off their lack of instrumental skills—Prince immersed himself in this New York scene, too, during the ‘70s—he was only too happy to flaunt his disrespect for traditional craftsmanship. Even contemporaries such as David Levinthal, who began in 1986 to photograph cowboy dolls and prop lassos for his Wild West series, knew the capabilities of the 20×24 Polaroid camera. He had learned the fundamentals of lighting and focus in an MFA program. Prince displayed no interest in training or technique.

The witty cynicism of the gambit—a photographic take on Duchamp’s ready-mades—undercut any interpretation of the series as nostalgia for the Old West, which was dying or dead as a viable genre when Prince was making the work. His denatured Cowboys have commonly been seen as satires of Ronald Reagan, the first president in American history with a Hollywood background. The former B-actor understood that the broad-shouldered Westerner (even if born in Illinois) was a powerful image to project to the nation and the world. More likely, though, the apolitical Prince was skewering the self-seriousness of fine art photography rather the ideological illusions of rhinestone cowboy Republicans.

It was his slacker attitude that angered the photography community. As Rubin puts it, “the fainter the markmaking, the more strident the critical carping.” Some of the outrage was misplaced. Crappy though they were as prints, his Cowboys were nothing if not purely photographic, without any multi-media trappings. The outrage at the art world, though, was justified. No one would have cared about Prince’s appropriations of the Marlboro Man—almost certainly not the contract photographers who worked for Burnett—if, as Rubin argues, the prints had not begun to bring staggering prices. As he points out, no one had protested in 1992 during his Whitney Museum of American Art retrospective. It was only after an example from the Cowboys series sold at Christie’s in 2007 for $3.4 million, the most ever paid for a photograph at the time, that the law suits began to fly. And yet, even though Prince certainly can’t be blamed for what collectors and museums are willing to shell out for his work, it’s easy to understand why a advertizing professional or an art school professor would resent him and despair at the market forces that have elevated Prince above everyone in history who has ever taken a photograph.

Rubin is a good friend of Prince and a big fan of his work. Don’t expect the disinterested opinions of a curator or scholar in the catalog. He doesn’t hide his admiration for the nervy devilishness of Prince’s appropriations. (For instance, the artist once hired an Icelandic book publisher to produce copies of Catcher in the Rye, replacing J.D. Salinger’s name on the cover and title page with that of Richard Prince. He then sold these “fakes” (or were they “originals”?) on the street for more than list price.)

Encyclopedic in his enthusiasms, Rubin nonetheless might have touched on the appeal of Western artists like Frederick Remington and Charles Russell for right-wing collectors such as Texas oilman Sid Richardson. Nor are there any excerpts from the writings of Karl May, the late 19th century German adventure writer whose stories of cowboys and Indians found a fanatical readership among the Nazis and are popular to this day through the Karl May Museum and annual festivals. More could have been said, too, about the cultural contradictions of the cowboy, working class but vehemently non-union, willing to trade low wages and the precariousness of being at the mercy of their employers for the freedom to ride off at any time to another job.

Today, the Western is a viable genre again, its nuances and subliminal messages studied in film and literature classes. The 1989 CBS broadcast of McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove was a surprise hit and saved the mini-series from extinction. Tarantino has made two critically sanctified Westerns, Django Unchained (2012) and The Hateful Eight (2015). He and Eastwood have inspired a wider appreciation for the career of Budd Boetticher. Following the success of McCarthy, young authors such as Téa Obreht, Paulette Jiles, and Sebastian Barry have felt comfortable setting novels in the 19th century American West, staking out new territory for gunslingers and pioneer women. Prince has played an unlikely role in this resurgence. His recent series of large digital landscapes depicting an empty Monument Valley (2016-17) suggest he wants to keep a hand in the game.

Perhaps Rubin shouldn’t be so quick to dismiss as venal or clueless the photographers who have taken Prince to court for copyright infringement. Even the humblest scribe, snapshooter, or art director has a right to feel violated if someone is making millions off your work without asking for your blessing. There is a reason no manufacturer of urinals, shovels, or bottle racks sued Duchamp: no one’s contribution of labor or finesse was disrespected when he put these utilitarian objects in a gallery or museum.

If by remaking Yojimbo as A Fistful of Dollars, Leone had to compensate Kurosawa monetarily for not seeking permission, why shouldn’t Prince have to make good to Philip Morris and the photographer Sam Abell for an even more direct act of thievery? In the Old West, someone who stole something from another and resold it for a profit would be at the mercy of frontier justice. Prince’s Cowboys have either proved definitely that we are living in a different era, where any image or words can be freely quoted, or he has pulled off the greatest robbery in art history.

Collector’s POV: Richard Prince is represented by Gagosian Gallery (here). Prince’s photographic works are ubiquitous at auction, with dozens of lots available every season. Recent prices have an extremely wide range, from as little as a few thousand dollars for large edition prints to as much as roughly $4 million for icons and rarities.

That was certainly a thorough round-up : )