JTF (just the facts): A total of 21 photographic works, variously framed, and hung against white and light grey walls in the main gallery space, in the entry area, and in a smaller front gallery. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 3 camera obscura Ilfochrome photographs, 2024, sized roughly 21×18, 24×19, 28×25 inches, 1 in a series of 3 unique photographs, 1 of 2 unique prints+1AP, 1 in a series of 2 unique photographs

- 2 camera obscura Ilfochrome photographs, 2024, sized roughly 32xx30, 11×9 inches, unique

- 6 camera obscura Ilfochrome photographs mounted to aluminum, 2018, 2021, 2023, 2024, 2025, sized roughly 48×43, 44×42, 36×47, 35×27, 31×28, 26×24 inches, 1 in a series of 4 unique photographs, 1 in a series of 3 unique photographs, 1 in a series of 2 unique photographs

- 2 camera obscura Ilfochrome photographs mounted to aluminum, 2024, sized roughly 31×30 inches, unique

- 1 set of 3 camera obscura Ilfochrome photographs and photograms mounted to aluminum, 2021, each sized roughly 49×43 inches, 1 of 2 unique sets of prints+1AP

- 1 set of 2 camera obscura Ilfochrome photographs mounted to aluminum, 2021, sized roughly 35×35, 35×17 inches, unique

- 2 Fuji Crystal Archive contact prints mounted to Dibond, 2023, sized roughly 47×77, 48×77 inches, in editions of 7+2AP

- 1 gelatin silver contact print mounted to board and mounted to aluminum, 2022, sized roughly 54×50 inches, in an edition of 7+2AP

- 3 multi-layered pigment print and hand-applied gesso on canvas, 2024, sized roughly 60×60, 25×25 inches, 1 in a series of 4 unique prints

Comments/Context: For a well-established mid-career photographer like Richard Learoyd, especially one who works in several genres at once rather than on discrete sequential projects, a new gallery show is an occasion for an update rather than a fresh introduction. How has he evolved his approach to portraiture and the nude figure? Or to the still life? Or to vast landscapes made outside the confines of the studio? We have seen consistent excellence from Learoyd in all of these areas before, and this show of recent works offers a sense of methodical artistic evolution rather than revolution, with small but consequential refinements, adjustments, and innovations pushing the British photographer’s aesthetics forward.

Aside from the inclusion of his work in various art fairs, it’s been a handful of years since we last caught up more thoroughly with Learoyd, with New York gallery shows in 2016 (reviewed here) and 2019 (reviewed here) culminating in a retrospective at the Fundación MAPFRE (also in 2019.) This show bridges that gap, with works stretching from 2018 through to 2025.

The fundamentals of Learoyd’s photographic process are worth reviewing, as they are vastly different than that of most other contemporary photographers working today. Learoyd uses a camera obscura, a centuries old process whereby light passes through a small hole and projects an inverted image of what’s outside onto the interior wall. Learoyd has harnessed this phenomena with his own room-sized camera constructed in his studio, whereby portrait sitters and still life objects are staged outside the camera and the light passes through a lens and directly onto light-sensitive photographic paper without a negative (i.e. positive to positive.) The resulting photographs have astonishing image clarity – especially when paired with long exposure times and clear light, the pictures are essentially grainless, even when the images are larger than life-sized. The camera also produces a relatively narrow plane of focus, which Learoyd meticulously places and controls, creating tight areas of extreme sharpness surrounded by softer zones that drift towards blur.

Learoyd’s portraits and nudes have long been his signature subjects, mostly because his process lends itself so extremely well to bringing out the subtle evocativeness and tactile lyricism of his sitters. Four recent portraits have been included here, in gauzy visions of red, green, and black, and each finds its way to that sublime point of tension, where our attention to the focal plane interacts with the nuances of facial expressions and wisps of hair. Both “Agnes in Red” (from 2018) and an “Untitled Portrait” (a woman in green, from 2024) find the elusive point of expressive uncertainty and fragility that makes a Learoyd portrait durably intriguing.

The knockout image in this show comes when Learoyd turns his attention back to the nude form. In “Cecilia after Subleyras”, Learoyd channels a c1732 painting by the French painter Pierre Subleyras, capturing not only the general pose of the original but mimicking its tiniest details of light, shadow, color, and glow. It’s simply a gorgeously elegant photograph, seen with a timeless sense of tenderness and subtlety. In other recent nudes, Learoyd becomes more strictly formal, creating an echo of curvature between a reclining nude and a bowl of lemons, and paying homage to Alfred Stieglitz’s photographs of Georgia O’Keeffe with an intimate image of interlocked hands set against the model’s chest.

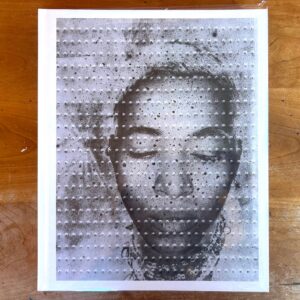

One of Learoyd’s newest approaches features fragments of earlier portraits turned into large scale heads printed on canvas. Apparently, this process of laying down pigment is decently precise, so the photographer can control the relative areas of light and dark in each pass; with sanding taking place between the layers, the painterly effect is something almost like dodge and burn in the darkroom, with Learoyd playing the image, amplifying and muting different areas as he goes along. The resulting works have a different textural quality than the standard photographs. Of course, printing the images on canvas gives them heft, but the printing process feels somehow softer and more burnished up close, with areas of blur becoming even more lushly indistinct. From afar, the oversized heads can be almost intimidating, but up close, they are altogether delicate and sensitive.

A number of still lifes are sprinkled through the show, as is Learoyd’s usual practice. A few use the thin lines of fishing wire or thread to truss up, extend, or hang the items in the air, as seen in a blue feathered wing and a grouping of three silver mackerel. This is an aesthetic approach he has used liberally before, which provides a way to get objects up off flat tabletops and into floating three dimensional space where Learoyd can then apply different light and focus choices. Elements of passing time activate several floral bouquets of tulips and poppies, with the individual blossoms in various states of bending, drooping, and decay; the brand new poppy image in particular has a somewhat hidden layer of playfulness, with glass eyeballs hovering in the water of the vase. Two other images make antique mirrors their ostensible subject, with misty scuffed reflections of eyes and candle flames reflected in the glass, creating a sense of misdirection or indirect seeing and watching.

A wall-filling triptych of elephant skulls finds Learoyd iteratively experimenting not only with positioning (the skull is rotated in alternate directions), but also with his thread line motif. In the past, the threads and wires have been largely functional, but in this work, they become more abstractly geometric, criss crossing in front of the skull rather than holding it in place. In fact, one set of the thread lines was actually made in camera as a photogram (with white threads appearing as black lines), with another layer of white threads seen in the exposure. Up close, it’s difficult to discern the difference in placement, leading to a netting of geometries that seems to divide and measure the hollowed out skull with angular precision.

When working outside making his large scale landscapes, Learoyd uses a different set of tools, including a portable camera obscura that creates a negative image (rather than a positive), which enables the landscapes to be contact printed (at sizes up to 80 inches wide) as editions. And while Learoyd has memorably ventured to Yosemite and elsewhere around the world, his new color images document the epic vastness of the Grand Canyon, like the 19th century survey photographers of old. Catching the scenes at the last light of the day, when a diffusing softness settles over the land, his works are astonishingly detailed from edge to edge, capturing the textures of dry mesas and rock canyons with precise fidelity, seemingly down to every last ripple of eroding sand.

Seen together, this show has the feeling of a mature photographer going in multiple directions at once, testing, extending, and refining approaches that have already proven successful in ways that only he can grasp. The connecting thread through them all is Learoyd’s use of the camera obscura to wrestle with the subtleties of light. When he finds just the right combinations of exacting stillness and luminosity, his works lift off from their typical photographic boundaries and start to feel intensely present. That he achieves this elusive magic not just once but a number of times in this show is reason enough to stop in for a visit.

Collector’s POV: The individual works in these shows range in price from $20000 to $100000, based on size and number of prints. Learoyd’s work has had only an intermittent secondary market presence in the past decade, with recent prices ranging in a relatively tight band between roughly $23000 and $60000.