JTF (just the facts): Co-published in 2024 by Dalpine (here) and Kutxa Fundazioa. Hardcover slipcase (29.7×21 cm) with hardcover folder and five softcover staple-bound zines, a total of 180 pages, with 24, 18, 32, 22, and 32 color reproductions respectively. Design by Tipode Office. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: While a formal hardcover photobook monograph is the desired format for publishing work for most photographers, there is something altogether artistically freeing about the zine as mode of visual communication. Not only is a zine relatively inexpensive to print and distribute, it can often be put together quickly, with less constraints on design and production, allowing smaller projects to get out into the world much faster. In some cases, a zine can be autonomously shot, edited, and produced dynamically, even in the span of a single day, opening up wider possibilities for experimentation and risk taking.

In the past decade or so, in addition to making several notable photobooks with his longtime publishing partner Dalpine (including TOT in 2022, reviewed here, and Estudio elemental del Levante in 2020, reviewed here), the Spanish photographer Ricardo Cases has also been using photozines as a way to bring freshness and responsiveness to his photographic practice. In walks around his hometown of Valencia, Cases has made photographs of his visual discoveries in various neighborhoods, turning them into single subject zines on everything from a massive ficus tree situated at a gas station to the patterns in an underwear shop window. In this way, his improvisational zines have become a rich vehicle for photographic exploration, something like essays, meditations, or visual journaling, where he can quickly organize his reactions and finds into tightly-edited gatherings of imagery.

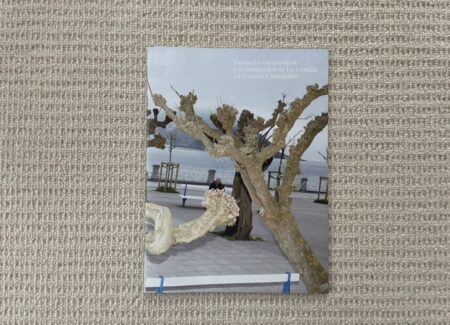

Los tamarindos de La Concha is a hybrid publication of sorts, part monograph and part zine. Five separate zines, made by Cases in 2024 in the city of San Sebastián during an artist residency with the Kutxa Fundazioa, are presented in a hardcover folder, which is then housed in a hardcover slipcase. The combination design is a convergence of ideas, successfully preserving the immediacy of the zine format, while wrapping the zines in a much more durable and protective package more conducive to wider book-style distribution methods.

As with any artistic residency, Cases was able to step out of the everyday rhythms of his home life and drop himself into an unfamiliar (but inspiring) place, hopefully creating the conditions for new ideas and connections. And like any photographer transported to a new location, he had to find a way to adapt his own unique visual style (and artistic vantage point) to the possibilities found in the local surroundings. So Cases wandered the streets of San Sebastián, responding to the city, with the intention of making a series of zines.

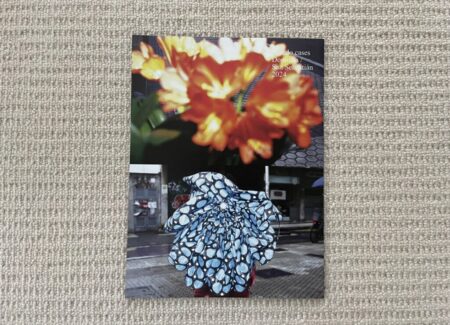

Two of the zines in Los tamarindos de La Concha are essentially up close studies of single subjects, with Cases then creating typology-like presentations of repeated forms that can be compared. One zine pairs blurred floral blossoms set against the backdrop of the city with open umbrellas (with similar urban surroundings) seen head on. Both provide splashes of central color against the greyness of city sidewalks, and they generally share a radial structure, with flower petals and umbrella segments arrayed around a central axis. When placed together in visual dialogue, the forms feel interchangeable (even when the umbrella patterns feature spots, stripes, camouflage, or animal prints), decorating the city with blasts of bright color.

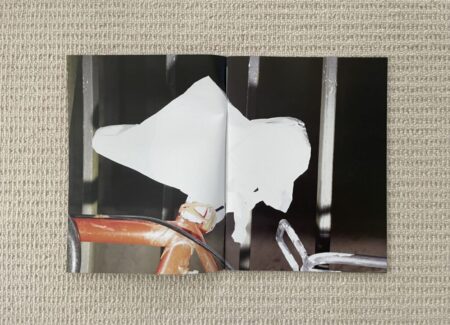

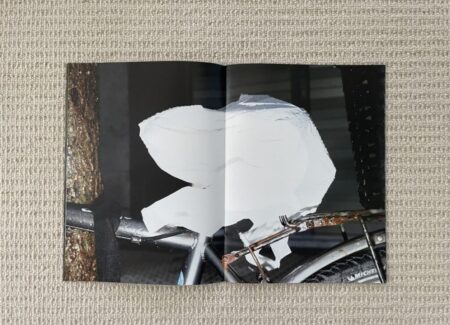

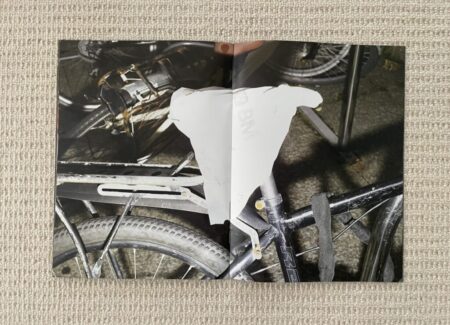

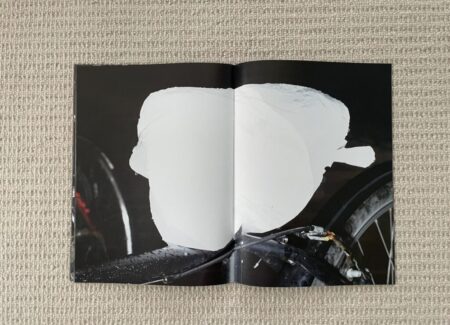

The other zine features the white plastic shopping bags people place over their bike seats to keep off the rain when the bikes are parked somewhere. Cases gets up close to these covered seats, bathing them with blinding flash and amplifying their formal qualities. While such wrapping might be a ubiquitous (and therefore overlooked) trend around San Sebastián, Cases’s attentive eye makes the covered seats almost ghostly, like bleached heads. Bike frames, handlebars, and wheels provide come visual context, with sidewalks generally blurred in the background. The resulting images are presented full bleed across the spreads of the zine like portraits, creating a one-after-another parade of mysterious covered whiteness, each one identifiable but still altogether secret and unknown.

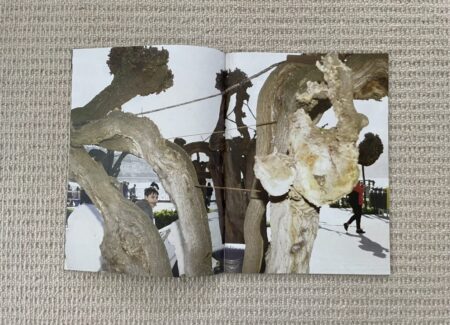

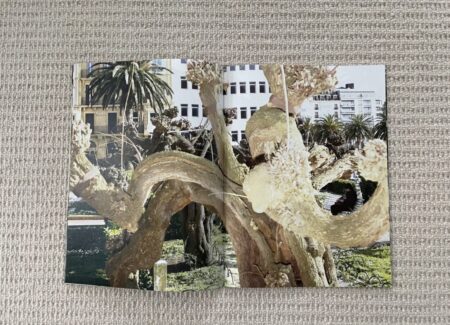

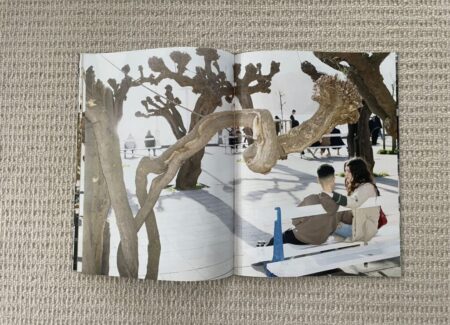

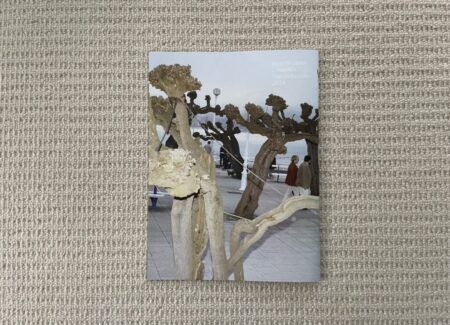

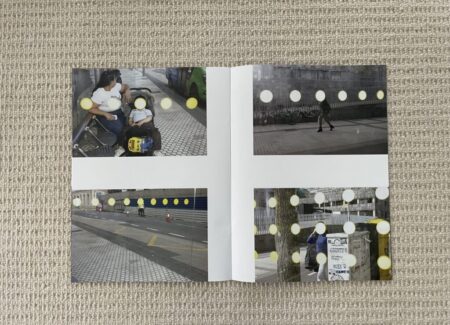

Another two of the zines use clever visual misdirection as an artistic strategy. One employs the signature tamarind tress on the boardwalk near the beach of La Concha as a screening element, placing pedestrians, passersby, and people sitting on benches within the twists of their branches. Again, Cases adds artificial flash to the available sunlight, giving the nearest branches and pruned stumps an invasive washed out blur. Cases then carefully situates his subjects amid the curves, each image becoming a kind of guessing game of where the people might be hidden. Some compositions capture two or even three groups of people inside this natural framing, transforming the typical tourist views of the boardwalk into scenes of orchestrated interruption and intrusion.

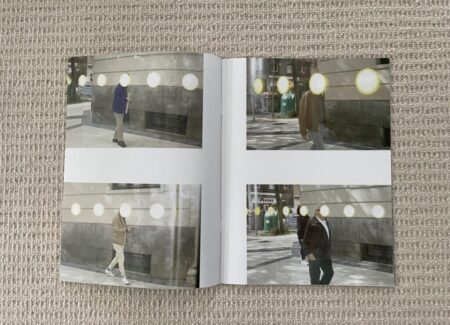

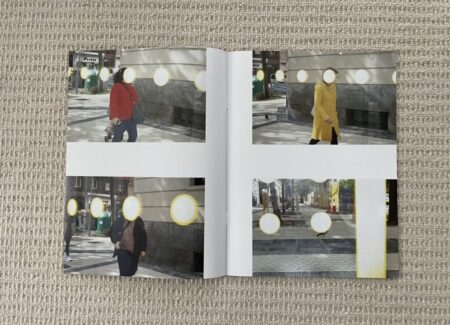

The arrays of yellow spots on the walls of San Sebastián’s bus stops provide Cases with another unexpected opportunity for misdirection. Shooting through the sides of the shelters and back toward the sidewalk, he aligns the spots to block the faces of the people nearby, in a manner similar to John Baldessari’s use of colorful spots. In a display of exacting compositional control and precise timing, Cases gets the right sized spots over faces again and again, the people (and even one pigeon) going this way and that, creating a kind of comic anonymizer. As the pages of the zine turn, the spots bounce along and obscure faces, like a rhythmic pulse or a resolutely analog overlay.

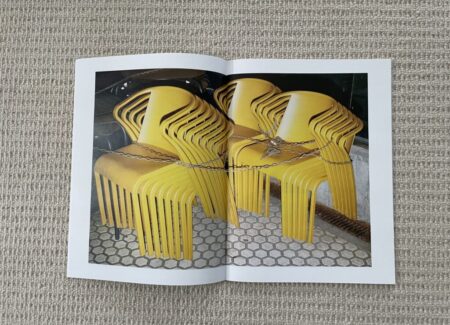

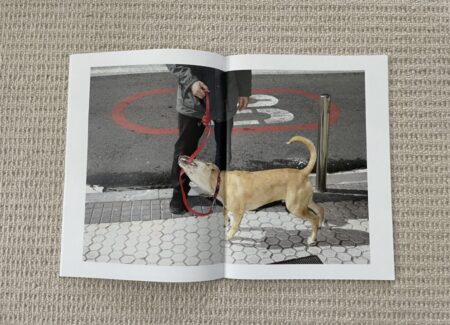

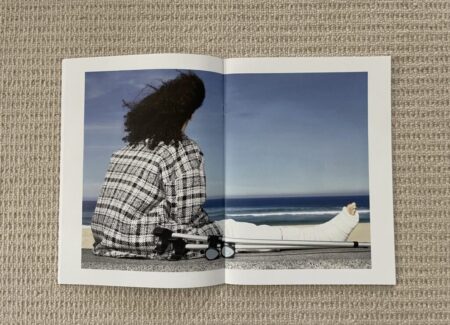

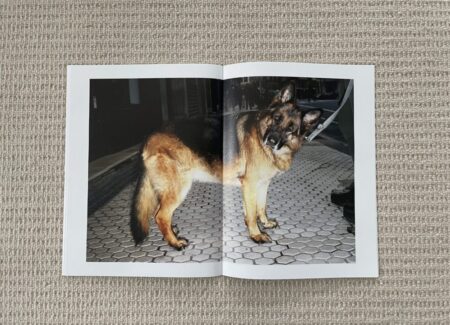

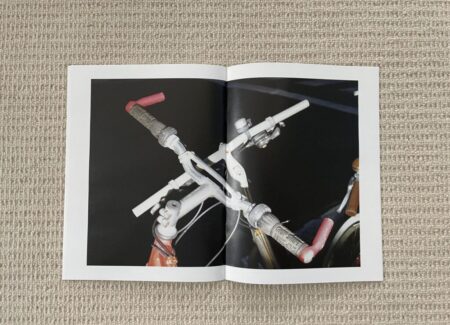

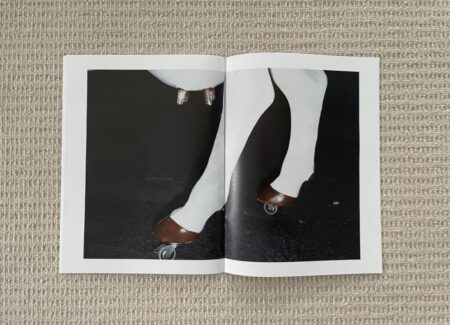

The last zine in the photobook is titled “D salia” (or D series) and gathers together an eclectic group of Cases’ observations from around town. Thematically, the images included in this zine jump around a bit, many experimenting with bright white and patterns of black and white. Cases notices a thicket of white flowers, the spots of a Dalmatian dog, the long blowing hair of woman dressed in white, the black-and-white plaid coat of a woman with a broken leg, the white legs of what looks like a cow on wheels, a man in a white robe on the beach, as well as various white cars, white railings, white stairs, white silhouettes, and white stripes. He then balances these whites with a few blasts of primary color, in the form of a man in a blue track suit near a blue ship, a red scarf, a red dog leash near a red circle on the pavement, a red sweater, and some stacked yellow chairs. Other found oddities include several quizzical dog expressions, beer foam that looks like crashing waves, pairs of crossed bike handlebars, and various peek through setups using trash cans, barriers, and the underside of a dog. Seen as a continuous flow of observation, this zine finds Cases playfully interacting with the city, finding plenty of visual interest hiding in plain sight.

Seen together, Los tamarindos de La Concha feels like an actively multivalent study of someplace new to the artist, like a self-imposed test of his creative problem solving skills. The intimate library (or family) of zines format is wholly successful, making each idea Cases has explored in San Sebastián discrete but integrated into a larger thematic and stylistic whole, as enclosed in the hardened slipcover. With a layer of project curation on top of the image editing, his approach makes testing and trying any particular line of artistic thinking less risky, thereby encouraging even more outlandish or marginal ideas to be explored more fully; a project no longer requires fifty (or more) “good” images to be valid – even a dozen intriguing pictures on a small theme might make for a compelling zine, especially if it riffs on the aesthetics of other zines in the collection. In this way, Cases may have opened up a new way of working for himself (and the others who may follow his lead), with a flexible structure that inherently makes room for experimentation.

Collector’s POV: Ricardo Cases is represented by Angeles Baños in Badajoz (here) and EspaceJB in Geneva (here), among others. His work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.