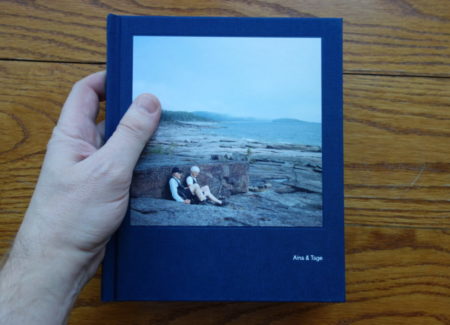

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2017 by Journal Photobooks (here). Hardcover, cloth bound, 72 pages, with 32 color reproductions. Includes a short essay (in English/Swedish) by the artist and a letter/caption by the artist’s grandfather (also in English/Swedish). (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: When photographers search for subjects, proximity and access are often important and in some cases even determining factors. Parents and grandparents can generally be counted on to be both somewhat nearby and at least minimally willing and supportive participants, and there is always a sense of mystery between the generations, as younger people try to understand the overlooked backstories, choices, and behaviors of their elders. So photographic essays documenting the lives of parents and grandparents are a common staple for amateurs and serious artists alike, to the point that even when they are done well, they can follow predictable lines (aging, bodies weakening and slowing down, sickness, the strength and weakness of relationships, loneliness, and sometimes even death). But the simple universality of human experience means that these visual stories still resonate with us, regardless of whether we have seen them before.

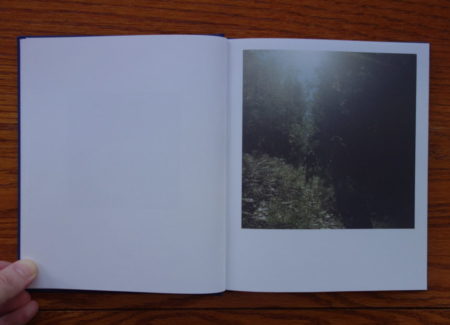

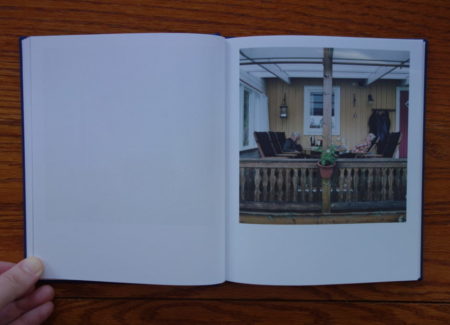

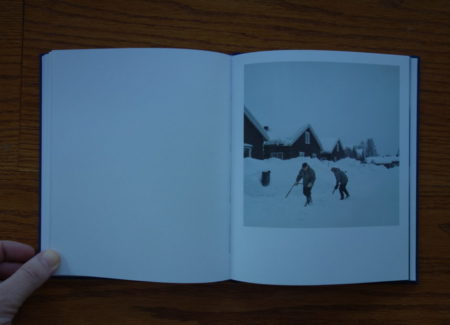

Rebecka Uhlin’s book length portrait of her grandparents Aina and Tage is affectionate and modest. It captures the pair at their house in the country, where nearby forests surround vegetable gardens and greenhouses, and the slower pace of life allows for clotheslines, transistor radios, workshops in sheds, and attentive hikes in the woods. There is no major drama to be found here, no shouting, or estrangements, or angry tears, at least as shown in this essay. What is captured is the quiet patience of everyday rhythms, where the wind rustles the blooming wildflowers and the snow covers the farmland in winter.

The first thing I noticed about Aina & Tage is just how smartly sized it is. It fits perfectly in my hands (see the picture above), not too small so as to feel overly precious and dainty, not too big to take on airs of importance or formality, but slender and drawn in enough to feel intimate and personal. This seems like a tiny unimportant detail I realize, but the size of this book is a design triumph to be celebrated – it feels exactly right, and the sizing sets the mood from the get go, encouraging the viewer to enter Uhlin’s narrative with just the right set of unpretentious expectations.

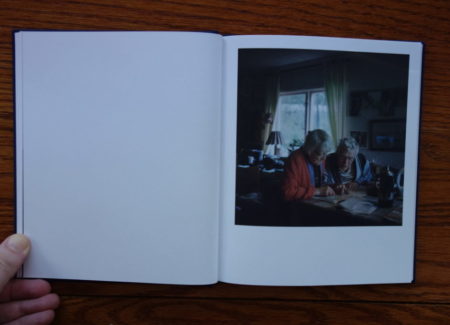

The tenderness that flows through this photobook comes on two levels, both from the subtleties of how Aina and Tage relate to each other and from how the granddaughter has made her photographs of them. The photographs are filled with understated emotions and easy going companionship. He digs up the plants she’s interested in. She holds the ladder while he puts up the Swedish flag. He helps her read a map. She gently removes something from his eye.

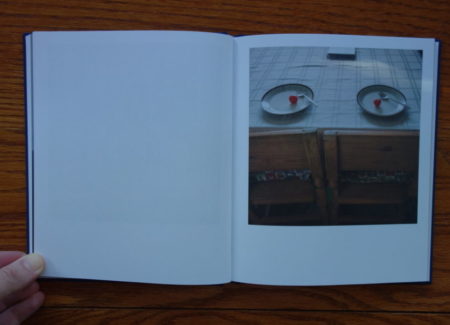

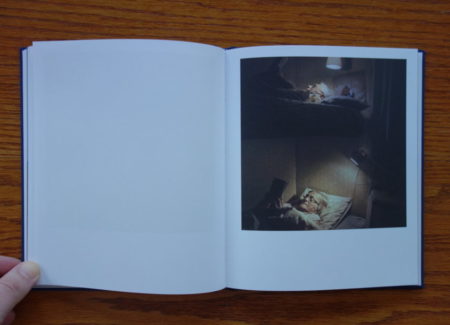

Uhlin’s photographs capture these overlooked moments of togetherness, and the many routines the two have built over a lifetime. They fall asleep in their chairs on the porch. They sit on the same side of the table at a diner. They read in their bunks, one atop the other, each with their own light. They gamely shovel the deep snow in matching grey parkas. They cross country ski together in the woods, and go hiking on the seaside rocks, resting now and again. Perhaps the best picture of this sympathetic co-dependent caring is one where the two protagonists are actually absent, their places set at the lunch table, each plate holding a fork and single ripe cherry tomato.

What Uhlin’s pictures document with so much grace is the comfort the two have built together. In single portraits of one or the other, they both look at ease, each comfortable in his or her own aging skin. Tage goes shirtless in the workshop, in the greenhouse, and out among the plants in the summer, his bright eyes undaunted by his sagging skin. Aine washes her feet in a bucket, hangs up the rugs on the clothesline, and dons a smock dress, her hair in a messy swoop. Their lives together feel practical, and full of healthy work, and still decorated with small shared joys.

It isn’t easy to pull off this kind of genuine warm-hearted humanity without drifting into syrupy sweet imagery that feels forced. But Uhlin’s photographs never try too hard. She perceptively finds the moments when kindness, and unselfishness, and compassion come forth, and allows us to tag along and vicariously embrace that elusive authenticity.

In the end, Aina & Tage is a book many will discount, its content seeming too obvious. But its subtle emotions and quiet admiration are what durably resonate. This is the kind of overlooked photobook I can imagine pushing on friends and colleagues, urging them to trust me that its modest appearance hides something worth discovering. “Just hold this book in your hands for a second” I will say, and its invitingly unpretentious magic will do the rest.

Collector’s POV: While Rebecka Uhlin is starting to have her first round of solo gallery shows with this body of work, it isn’t entirely clear which of those will develop into representation relationships. As such, at least for the moment, interested collectors are likely best advised to connect directly with the artist via her website.