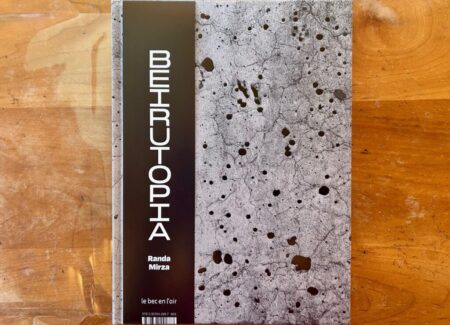

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by Le Bec en l’air (here). Hardback with movable belly band, 10.5″ x 8″ inches, 224 pages, with 279 color reproductions. Includes essays by the artist and Rahsa Salti, with excerpted texts by Ghada Assaman, Dominique Edde, Liliane Buccianti-Barakat, Samir Kassir, Sahar Mandour, Samer Frangie, and Ghada Sayegh. Texts in English/French/Arabic. Design by Hatem Imam, Studio Safar, Beyrouth. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Randa Mirza is a Lebanese multidisciplinary artist born and raised in Beirut. Although she now splits her time between there and Marseille, France, her photographic heart is still firmly anchored in her home city. The Lebanese capital provides the etymological root of her monograph titled Beirutopia, and its battered streets are the source material for all of its images.

A fascination with the security of home might be the natural outgrowth of a childhood rooted in strife and uncertainty. Mirza was born in 1978, in the midst of the Lebanese civil war and just before the second Israeli invasion in 1982. As she describes her formative experiences in Beirutopia’s opening essay, “I grew up in West Beirut during the civil war, right by the demarcation line that divided the city. During my childhood I lived through heavy indiscriminate bombings, shootings between neighborhoods and nearby homes…We practiced forgetfulness as a survival skill, living day to day, with no yesterday or tomorrow.”

In the context of deliberate amnesia, Mirza’s various photo projects might be considered a step toward reclaiming memories. She’s photographed in and around Beirut since 2000, using a range of approaches. The resulting images are partially targeted at the fine art world. But just as importantly, they document physical evidence of the city’s enduring post-war history.

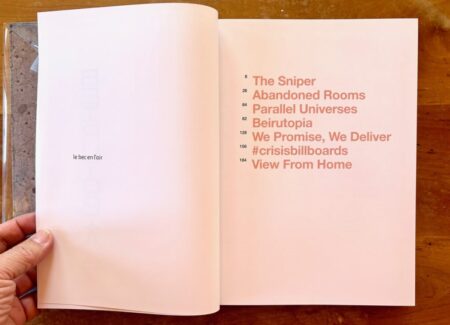

Seven photo series comprise the book. They are sequenced in chronological order, each one prefaced with an excerpt from a prominent regional scholar: The Sniper (2000-2002); Abandoned Rooms (2005-6); Parallel Universes (2006-2009); Beirutopia (the title series, shot 2010-2019); We Promise, We Deliver (2020-21); #Crisisbillboards (2020-22); and View From Home (2020). In addition to the monograph, Beirutopia was shown as a survey exhibition during the 2024 Rencontres d’Arles.

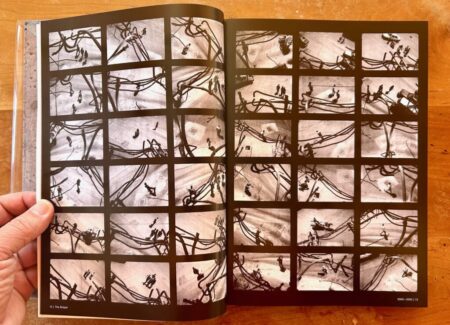

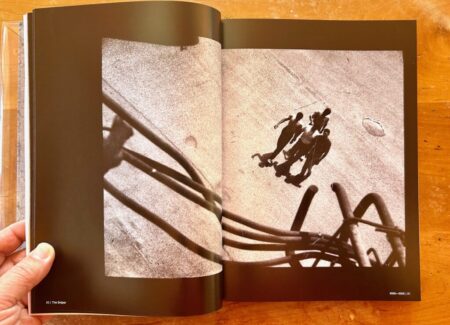

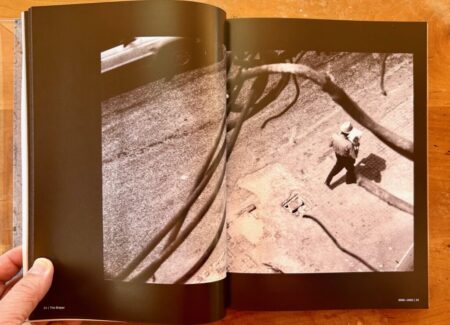

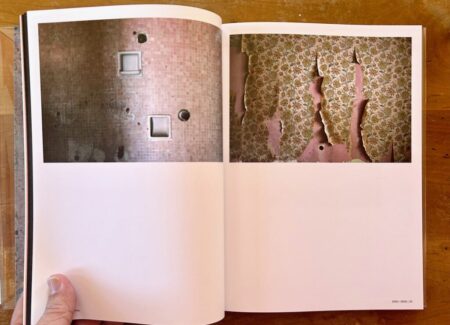

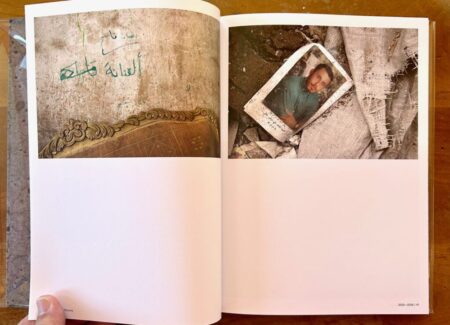

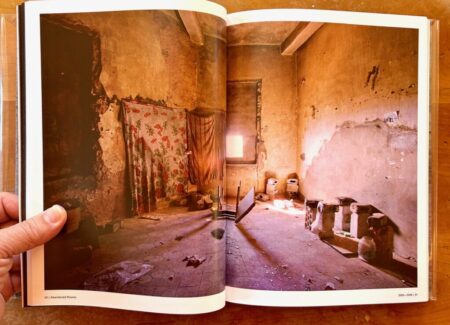

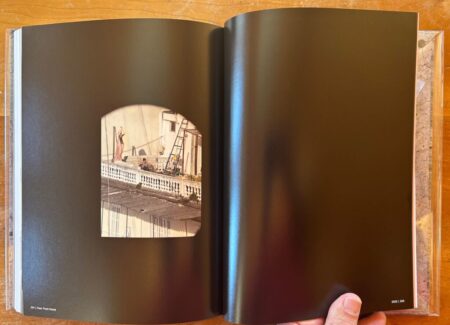

The reader feels the weight of war immediately in the book’s first two photo series, The Sniper and Abandoned Rooms. Mirza was still in her early twenties when she conceived these. With battle traumas still fresh in her mind, she confers her headspace directly to the viewer by making photos from, through, and of war damaged buildings. Sneaking into the upper stories of these places with her camera, “I could see without being seen.”

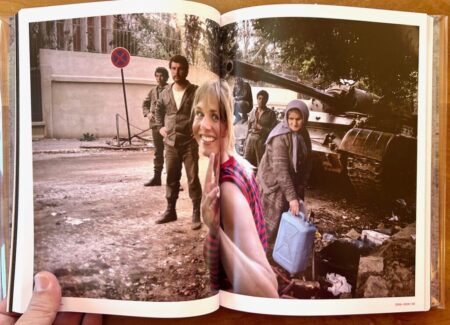

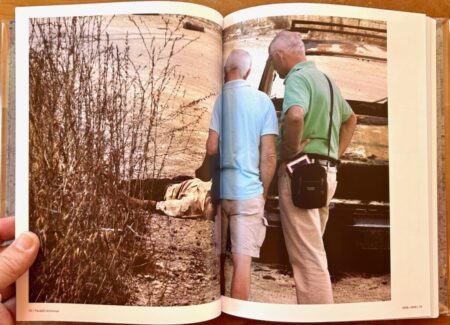

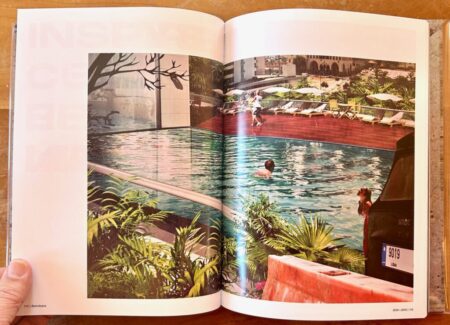

The Sniper surveils the city streets below with martial monochrome efficiency, while Abandoned Buildings documents artillery scarred interiors ravaged by years of conflict. If both series leave the viewer feeling unsettled, Parallel Universes pounds the psychic turmoil home. The series employs digital collage to juxtapose Beirut’s carnage with peacetime rituals. Two men sip Cokes near burning tires in one image, for example, while another captures a woman clicking her TV remote while seemingly ignoring a nearby combat casualty. Composited in the early days of Photoshop, these montages are not technically proficient compared to contemporary methods. But they make up for their rough edges with on-the-nose candor, which lands between black humor and blunt shock value.

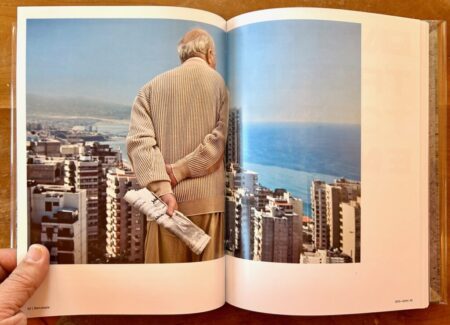

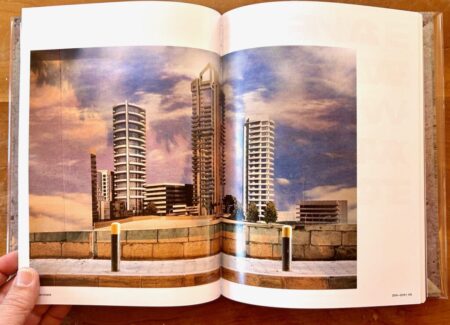

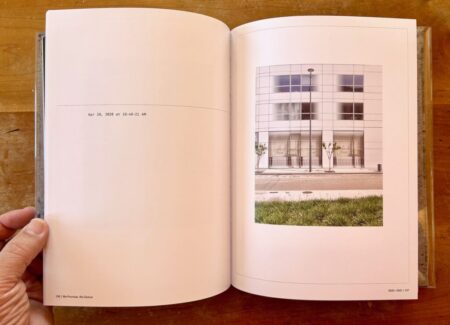

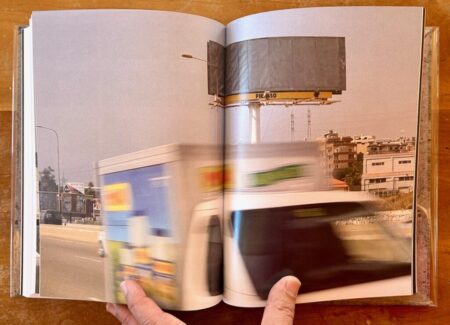

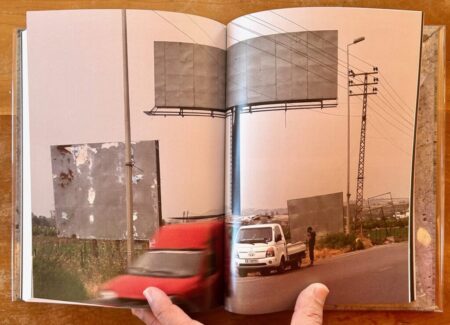

With the title series Beirutopia, Mirza finally settles into her mature groove. The photographs are straight documentary this time, not Photoshopped, but they mix disparate subjects with similarly jarring dysphoria. The pictures show real estate advertisements in Beirut, captured on billboards in the context of unimproved city streets. Mirza spent ten years on this project (2010-2019), and gradually honed a keen trompe l’oeil style of composition. The majority of space in her frames is taken up with ad content. We witness one aspirational fantasy after another, as the eye casually consumes a world of ritzy hi-rises and luxury furniture.

The initial effect is tantalizing, but it doesn’t last long. The photo edges send the viewer back to Earth by showing clumps of the surrounding world. The billboards are buffered by broken paving stones, construction cones, and worn bollards. It’s the epitome of banal, and a far cry from Beirutopia. City residents can day dream for a moment, it seems, but their waking reality remains the same as ever. Beirutopia is a clever real-world improvement on the discrepancies of Parallel Universes, and recalls the visual twist of Nick Relph’s book Eclipse Body and Soul Syntax (reviewed here), which also leveraged real estate ads for ironic effect. With the fantasy/concrete juxtaposition transferred now to a post-war zone, it becomes that much more powerful. In my opinion, this is the strongest series in the book.

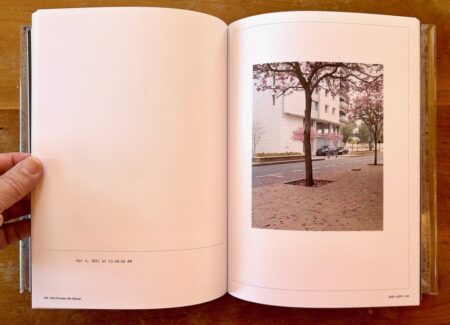

The final three series document aspects of post-2020 Beirut, in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic. As in the rest of the world, shutdowns and social distancing created a blank spot in the cultural fabric there. Photos of vacant sidewalks, unmaintained streets, and empty road signs signal a general malaise. #crisisbillboards drive the point home with serialized still frames of catatonic social scapes, a repetitious purgatory of non events.

With the last series View From Home, Mirza brings the pandemic full circle, by tying the malignancy of disease to the broken state of Lebanese government. Pictures zoom in on selected city scenes, captured both before and after the massive arsenal detonation which occurred in a downtown warehouse on August 4th, 2020. Buildings are shown intact, and then in ruins, divided by the knife edge of fate. The civil war may be long since over, but domestic turmoil is ongoing. By mimicking the view through binoculars, the photos reference both sniper surveillance and myopic leadership.

For Mirza, the August 4th accident was a physical manifestation of deeper dysfunction. In her opinion, the country’s leadership is inept and ineffective. “Lebanon has been sinking into a multidimensional crisis,” she writes. “Political, structural, moral, financial, social and sanitary all at once, affecting all sectors.” She doesn’t mention Hezbollah, Israel, Syria, or other regional actors, and she doesn’t need to. It seems Lebanon can beat itself up without any outside help.

Although it doesn’t document any actual real-time battles or violence, Beirutopia might be considered a book of war photography, or post-war as the case may be. Mirza’s subject is not tanks and guns, but instead war’s cultural impact and side effects. The book joins a slew of recent monographs in a similar vein, including An-My Lê’ On Contested Terrain (reviewed here), Debi Cornwall’s Model Citizens (reviewed here) and Necessary Fictions (reviewed here), Matthieu Nicol’s Fashion Army (reviewed here), Nikita Teryoshin’s Nothing Personal (reviewed here). Perhaps we have fully transitioned from the boots-on-the-ground war coverage of Capa, McCullin, and Natchwey, and into a brave new photo world?

I can’t answer that question. But there is one key difference between Mirza and her war-adjacent cohort. All of the contemporary authors above approached the topic as outside observers, while Mirza has experienced war first hand. No matter how hard she might practice forgetfulness as a survival skill, bomb blasts still reverberate in her work. Beirutopia will leave many readers shaken. It’s also a memorable lasting memento.

Collector’s POV: Randa Mirza is represented by Galerie Tanit in Beirut (here). Mirza’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.