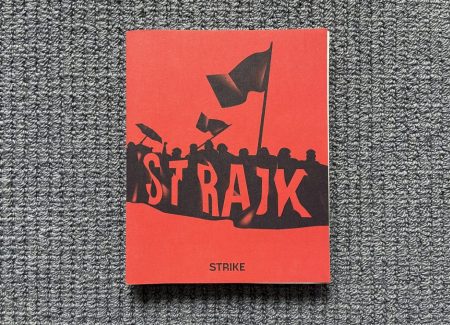

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by Jednostka Gallery (here). Softcover (165×207 mm), 256 pages (unpaginated), with color photographs throughout. Includes essays in Polish/English by Iwona Kurz, Karolina Gembara, and Aleksandra Boćkowska. Cover graphic design by Ola Jasionowska. In an edition of 2000 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

A special edition is also available, with a signed and numbered book by the artist with the graphic by Ola Jasionowska (signed and numbered by Jasionowska). In an edition of 50 copies.

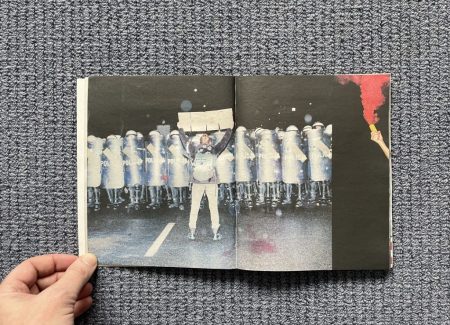

Comments/Context: Crafting a photographic narrative that documents a politcal or social protest can often fall into a surprisingly familiar set of visuals. We typically start with two opposing sides, physically separated (at least to begin with), with large crowds of generally peaceful marchers ultimately coming into confrontation with uniformed police or military forces that have been placed there to control or disperse them. The protestors (and their leaders) are often shown as individuals, with expressive faces, bold gestures, and clever signs, while the police are almost always faceless representations of monolithic power, clad in helmets and riot gear. When conflict occurs, the visuals inevitably become more extreme, with nighttime flames, clouds of smoke, and physical violence filling the photographs with chaotic emotional intensity, and in many cases, a symbolic visual of a lone protestor resisting a larger force is either staged as a provocation or emerges on its own. In the aftermath, we are reliably offered the imagery of arrests, bloodied faces, injured bodies on the ground, and broken debris strewn everywhere.

The reason that this particular photojournalistic framework has become so prevalent is that it works – out of the confusion and disorder of a protest that turns into a confrontation, it creates a simple us-versus-them (or David-versus-Goliath) narrative that can be quickly and easily understood by even the most uninformed viewer. And across the history of photography, we’ve seen plenty of examples of this form being used to compassionately and incisively document events around the world, generally taking shape as a multi-image photo essay (for a newspaper or magazine) or as a zine or photobook. Even in the digitally-dominated 21st century, protest photobooks still shape our understanding of social and political movements both near and far, from the recent Black Lives Matter and police brutality protests in the United States to the protests against politcal changes imposed by China in Hong Kong, among many others.

But not all protest, rally, and march stories need to be told in the same way, and over the past few years, the Polish photographer Rafal Milach has been thoughtfully experimenting with the protest photobook form, searching for alternate ways to create visual narratives. In the broadest sense, Milach has taken the ongoing transformations in the post-Soviet states as his subject, but of late, he has narrowed down to exploring the nuances of events in his homeland. His 2018 photobook Nearly Every Rose on the Barriers in Front of the Parliament was made in response to protests in the summer of 2017 against judicial reforms promoted by the right wing Law and Justice party. But instead of showing us the kind of protest scenes we have come to expect, Milach documented the white roses protestors attached to the crowd-control barriers in front of the Parliament buildings, and then crafted an accordion-style cardboard photobook that unfolded to replicate that barrier, with anonymous halftone images of uniformed men on the back side. It was a less literal, more symbolic approach to depicting the split taking place.

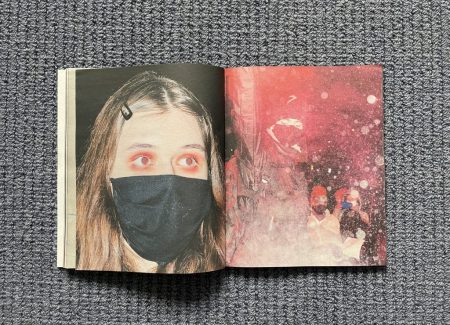

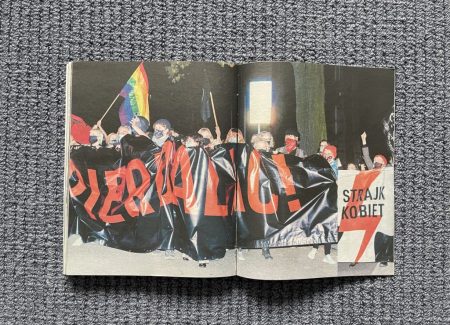

Over the subsequent years, the political situation in Poland has gotten more extreme, with stricter controls being incrementally placed on a range of social freedoms, including a near-total ban on abortion in 2020. This ban, as well as other discriminatory restrictions and regulations placed on LGBTQ citizens and other minorities, led to a series of protests in a number of cities that became the larger Women’s Strike, which Milach has documented in this photobook. But again, he’s taken an unlikely approach to telling his story, which meaningfully alters our perception of the dynamics of the situation.

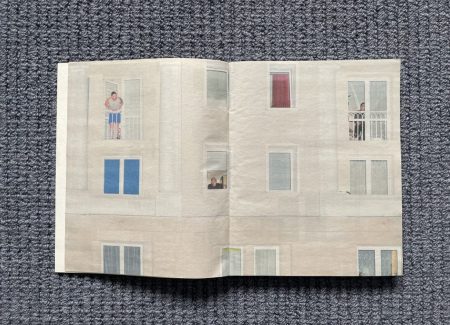

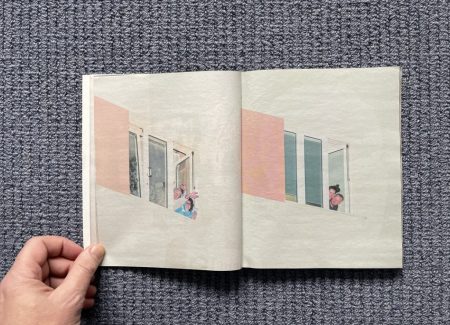

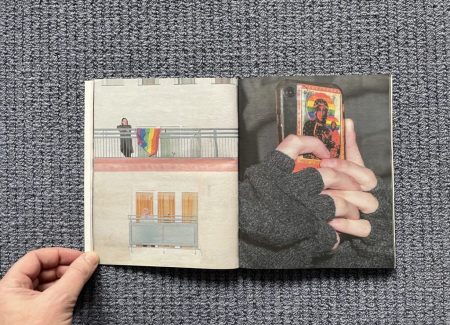

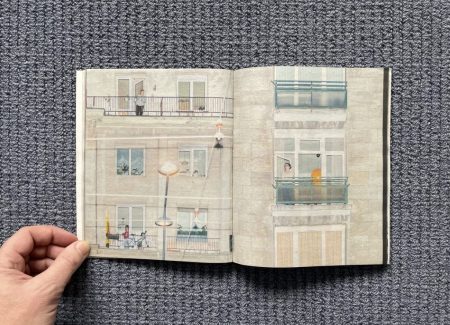

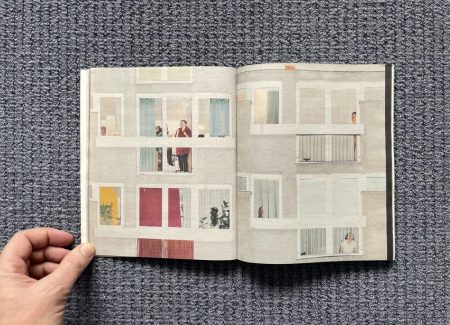

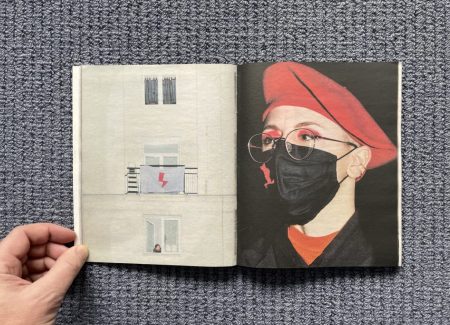

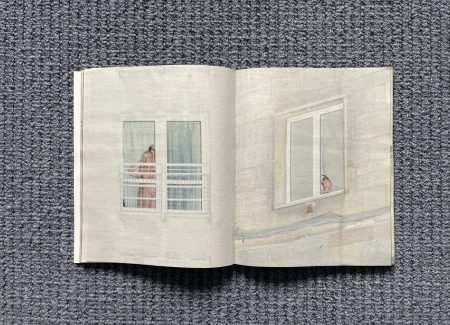

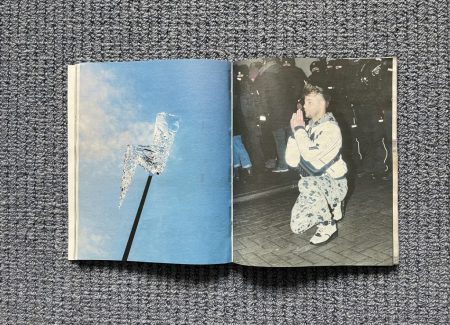

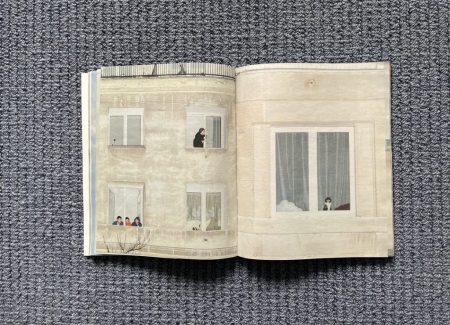

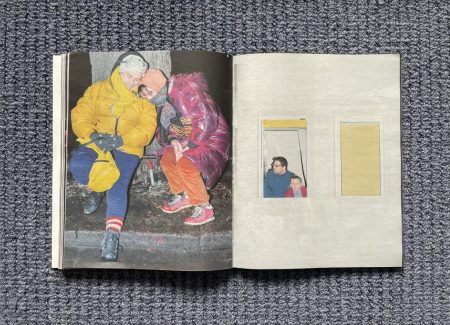

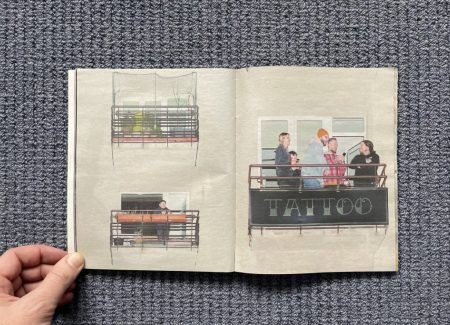

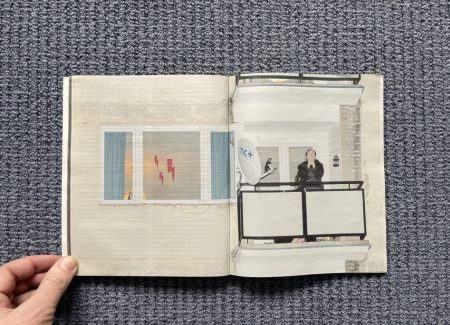

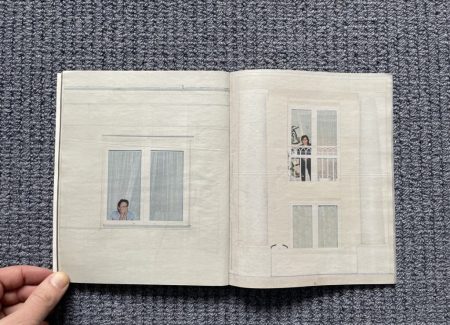

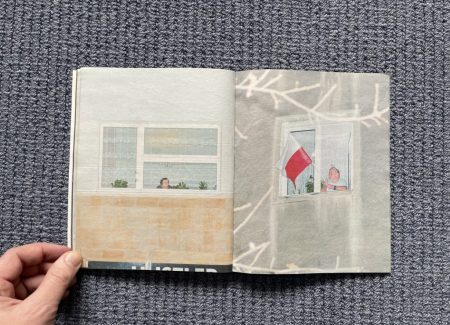

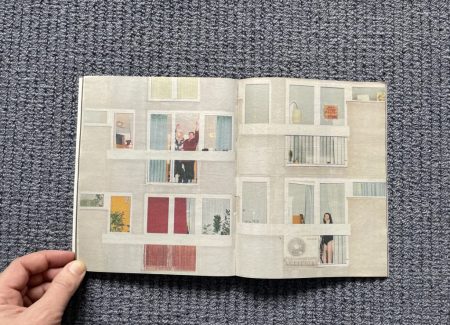

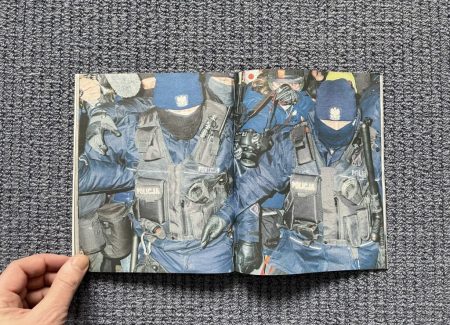

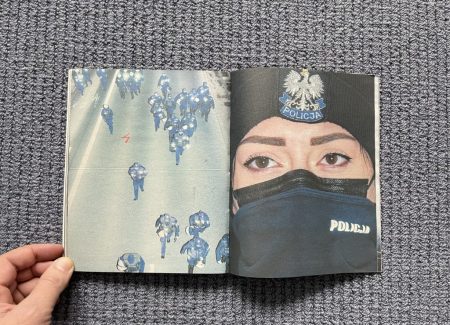

For the most part, Strike has very few traditional protest pictures. There are a couple of overhead views of marching crowds (seemingly all at night), and a few more of gathered police, but these photographs feel like atmospheric scene-setting and backstory rather than critical or propulsive documentation. Instead, Milach has opted to visually describe the Women’s Strike as a combination of two primary forces: those marching in the streets and those watching from their windows and balconies.

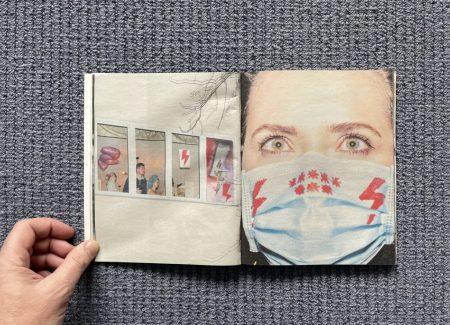

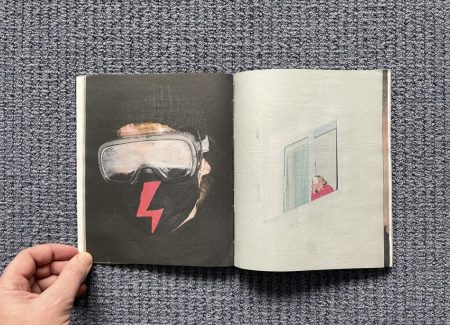

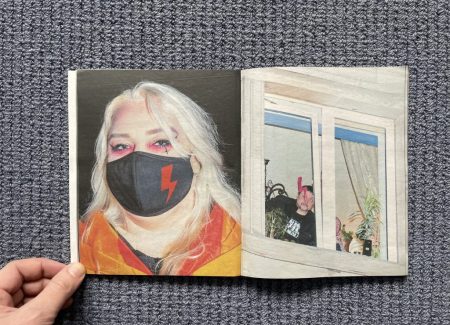

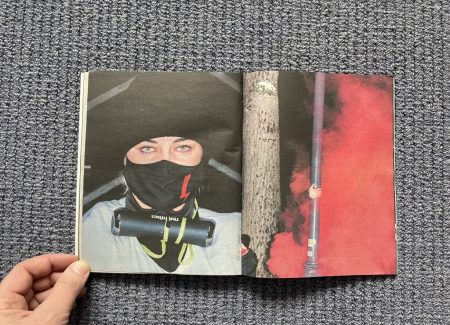

Since these events took place in the middle of the pandemic, they are set against a very real context of lockdowns, quarantines, and health concerns. All of the participants in the streets (both protestors and police alike) are masked, and not just to avoid the surveillance cameras, and those who stayed home may have wanted to be in the streets, but had the government mandates and potentially valid health constraints to consider. Going out to protest was a doubly risky endeavor at that particular moment, and both participants and witnesses seem to fully understand that reality.

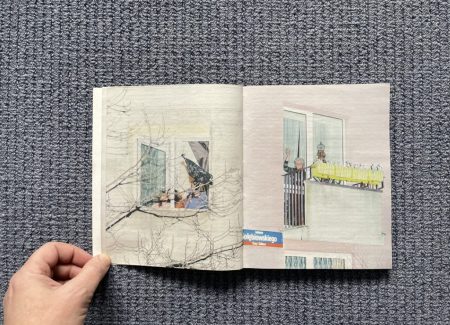

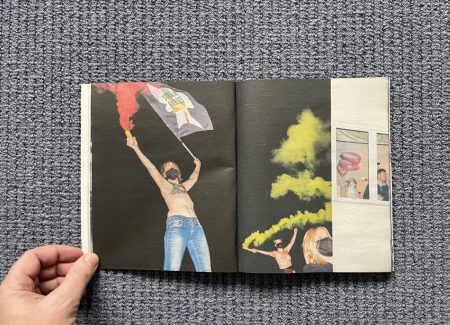

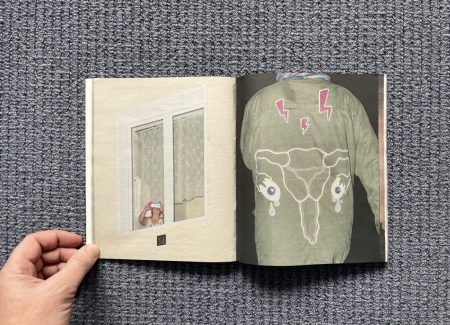

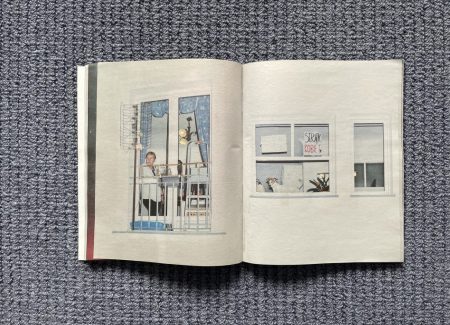

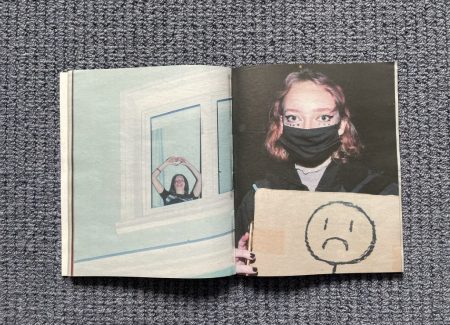

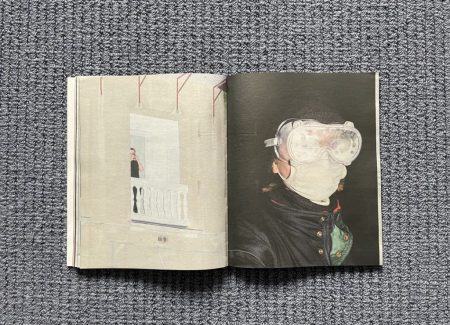

The reason we can guess at the mood of the larger society is that Milach has shown it to us, via images of people watching the protest marches from their windows. Strike is filled with flash-lit looks upward at windows and balconies, where people from all walks of life (families, couples, individuals, groups, children, old and young alike) peer down at the momentous events below. Some carry signs, banners, and flags, and wave and cheer with obvious enthusiasm and approval. Others look on with more anxiety, animated by clasped hands, anguished faces, or wary trepidation. The shy but curious peek out from behind curtains, while the expressive laugh, have parties, and get naked. And everyone is taking pictures, recording their own version of the unfolding events. In a few cases, Milach has captured grids of apartment block windows with most of the available vantage points filled with onlookers, as if the entire city was watching and participating from afar.

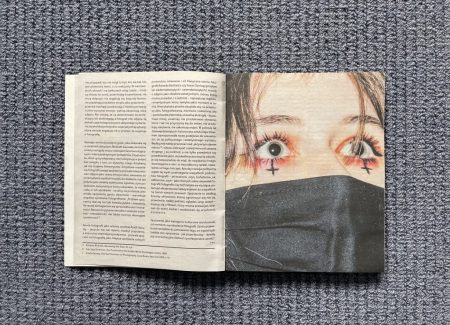

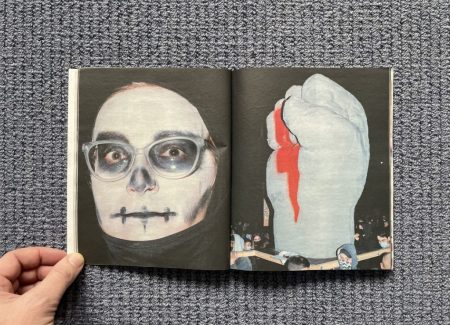

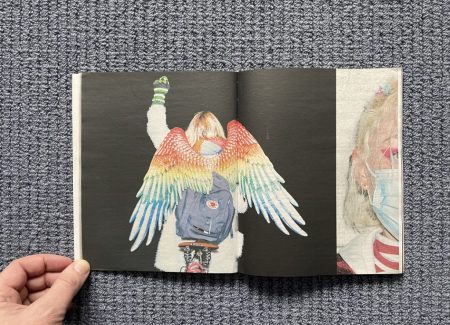

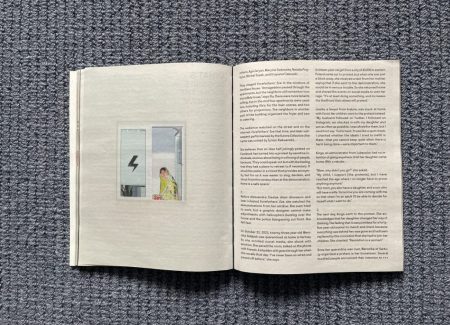

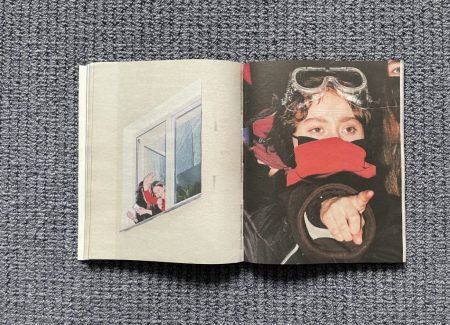

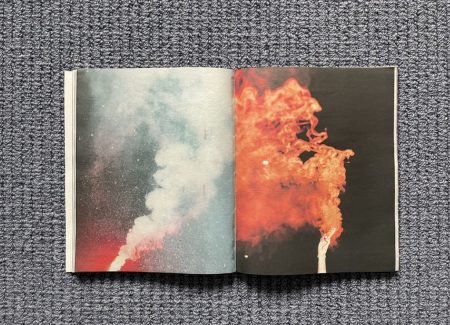

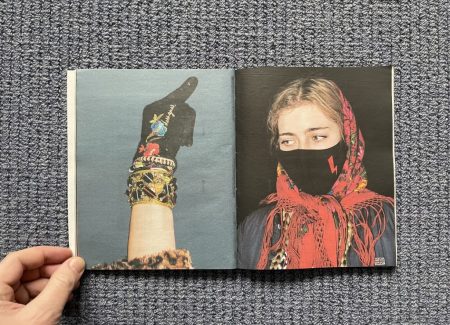

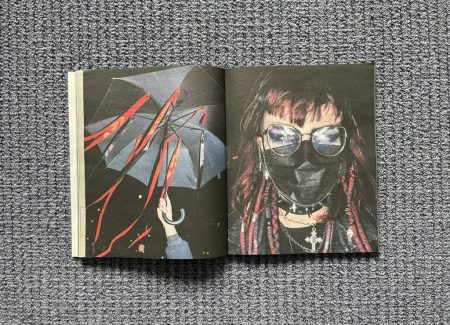

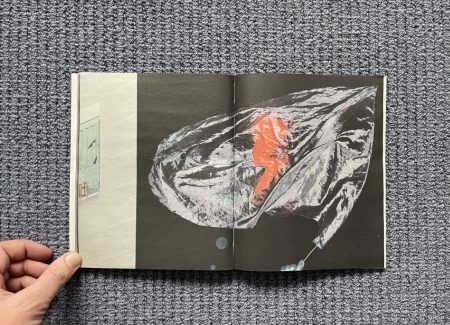

Down at the street level, Milach doesn’t sit back and observe from a distance; he gets right up close, making tightly cropped headshot portraits of the individual protesters. Between the pandemic masks and the symbolic makeup, many of the faces take on a performative angry Goth quality, with the movement’s red lightning bolt emblem featured prominently. This energy evolves toward spectacle in images of topless protestors holding colorful smoke torches and a bike-riding woman wearing rainbow angel wings, but Milach doesn’t drift too far from the faces, where pink ski masks, safety goggles, and black tears complete the exaggerated looks, and raised fists and middle fingers punctuate the shouts and cheers. In this parade, each face is both a specific individual and an anonymous character in the fight.

What’s most fascinating about Strike is this visual duality – between seeing and being seen, performing and observing, or exhibitionism and voyeurism, depending on how we define what’s going on. Most notably, Milach’s photographs point to the complex dynamics of group participation, and the ways in which a city (or a nation) communicates with each other and itself, and gathers consensus around important ideas. When framed this way, it’s almost as if the protest is a powerful method for engaging with (and galvanizing) the rest of the citizenry, almost more than it is overtly fighting the oppressors.

One of the other delights to be found in this photobook is a clear understanding of how to make an effective low-cost publication. Strike is being sold for €20 plus shipping, and has been printed in an edition of 2000, so it was deliberately designed to be widely circulated. But it isn’t “cheap”; it’s filled with some 250 color reproductions, is thoughtfully designed (with some images that wrap around the page turns to pull the visual narrative along), and includes three scholarly essays. And while it is printed on thin paper and in a more diminutive size than many books, it feel right-sized, and appropriately improvised to match the content. In fact, if the book had been hardbound, on luxurious paper, with perfect reproductions, all the rebellious energy of the book would have been drained away by such decisions.

In the past decade, Milach has proven himself to be both a rising star photographer and an innovative photobook maker, and Strike should be seen as an important step in that larger artistic trajectory. In boldly rethinking how to photograph a protest, he’s opened up a range of new insights into both the particular protests themselves and how we generally record them. From a photojournalistic perspective, he’s delivered the required first-hand evidence, but he’s done so from an unexpected vantage point that seems to freshen the analysis. He shows us protest as an expression of mutual visibility and responsibility, where demonstrator and spectator both have roles to play and lessons to learn. This unconventional view is at first unexpected and almost disorienting (why are we looking at the watchers?), but turns out to offer subtleties we would have missed if we had simply followed the “action”. By looking away from that seductive display, Milach has shown us something richer and rounder, where a strike in the streets can turn out to be more inclusive (and broadly supported) than we might have initially understood.

Collector’s POV: Rafal Milach is represented by Jednostka Gallery in Warsaw (here), and is also an associate member of Magnum Photos (here). His work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.