JTF (just the facts): A paired show of the works of Tina Modotti and Edward Weston, framed in black and matted, and hung against white walls and linen partitions in the main gallery space. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the exhibit:

Tina Modotti

- 20 gelatin silver prints, 1924, c1924, 1925, 1926, 1926/1977, c1926, 1927, 1927/1977, 1927/later, 1927-1928, 1928, 1928/1970s, c1928, 1929, 1929/1970s, 1929/later, sized 2×3, 4×3, 4×5, 7×9, 8×9, 8×10, 9×8, 10×7, 10×8 inches

- 10 platinum prints, c1924, 1925/later, 1925-1927, 1925-1928, 1926, 1926-1928, c1927, 1929, c1929, sized roughly 4×3, 5×4, 7×9, 9×11, 10×7, 11×8, 13×10 inches

Edward Weston

- 14 gelatin silver prints, 1924, c1924, 1925, 1926, 1926/later, c1926, c1926/later, sized roughly 4×3, 7×9, 7×10, 8×9, 8×10, 9×6, 9×7, 10×7, 10×8 inches

- 2 gelatin silver prints mounted on board, 1931, sized roughly 4×3 inches

- 1 platinum print, 1924, sized roughly 4×3 inches

Carlos Romero Orozco (images of Modotti and Weston)

- 3 gelatin silver prints, 1923, sized roughly 2×2 inches

Comments/Context: More than a century since it first took place, the storied collaborative relationship between Edward Weston and Tina Modotti remains a milestone in photographic history. The two initially met in Los Angeles in 1921, with Modotti, who was a film and theater actress at the time, soon becoming a model and romantic partner for Weston, who was relatively early in his photographic career and already married with children. Then in the summer of 1923, in the heady times of social reform and artistic flourishing in the aftermath of the Mexican revolution, the two moved to Mexico together, based on a deal that in exchange for Weston teaching her about photography, Modotti would manage his portrait studio there (she already spoke fluent Spanish). The pair ultimately made pictures and lived together in Mexico until 1926, when he returned to the United States; she stayed on for another few years, eventually leaving in 1930, when her active political ties led to her deportation.

This show gathers togethers images made by both artists during their time in Mexico, and while not as extensive as a similarly themed museum exhibit at SFMOMA in 2006, it certainly offers plenty of rarities collected by the gallery over thirty-five years. Hung as an intermingled installation, the show encourages a direct comparison of how the two photographers tackled similar subjects, creating a robust side-by-side aesthetic dialogue.

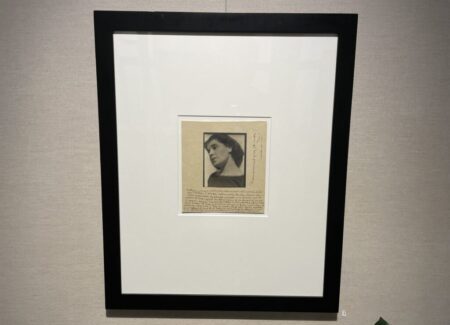

Chronologically, the story begins with three tiny images made by the painter Carlos Romero Orozco soon after Weston and Modotti arrived in Mexico City in 1923. While not much more than snapshots, they capture Weston in a suit and Modotti (ten years his junior) in a belted dress looking open and optimistic as they stand outside in the sun on a tiled patio.

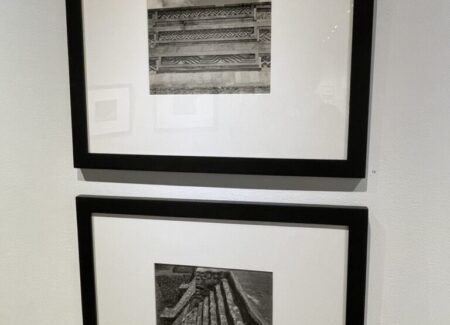

The images from a year later in 1924 are intriguing because they more clearly delineate the early collaborative situation. Modotti is seen as a muse for Weston, in a lovely head shot portrait in a boat neck dress and in a more seductive nude in an open robe. Weston’s other images from that year find him beginning to embrace a crisper Modernist eye, exploring Mexican folk art (in the form of a painted horse set against a woven rush backdrop) and ancient Mexican ruins (and the regular lines of stone stairs found there) as subjects. Modotti as a photographer, on the other hand, is learning to pare her compositions down to essentials, testing layers of textures and contrasts of light and dark; her early images of roses, the geometric turn of an interior stairway, and the darkened doorways of a convent all signal that she was a very quick study and was soon making images that rivaled her teacher’s.

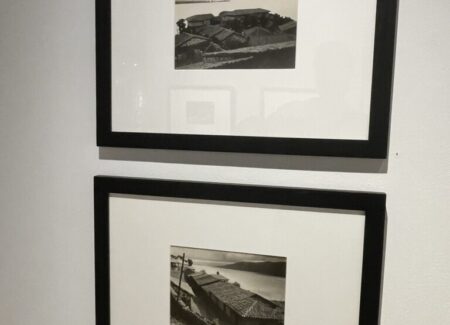

In the following year or so, Weston and Modotti follow similar aesthetic paths, particularly in terms of subject matter. They both make still life images of folk art and religious icons, as well as portraits of indigenous women going about their daily lives, walking through the streets, carrying things on their heads, and wearing traditional costumes. Local architecture is also a common subject, as seen in a side by side pairing of images of painted storefronts, one by Weston and the other by Modotti, both from 1926. For the most part, we might see the two as indistinguishable, as both are squared off, closely framed frontal views of buildings that feature painted signage and darkened doorways; perhaps the only clue to authorship comes with a few more local people to be found passing through Modotti’s composition, her commitment to photographing the lives of everyday Mexicans perhaps a bit stronger or more prominent than Weston’s.

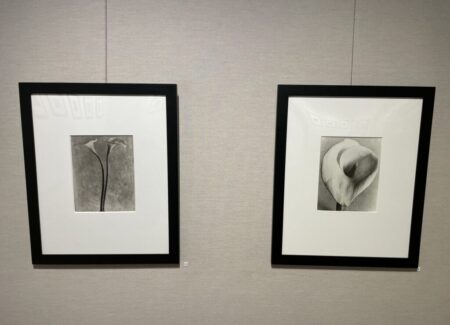

This show is a bit weighted toward Modotti’s work, which helps amplify how her activist interest in politics and social justice increasingly manifested itself in her picture making. Many of her photographs from this period celebrate the everyday work of women, including farming, cleaning clothes by hand, bathing, and caring for young children. Others push further to highlight the plight of workers, in images of weathered hands on a shovel, workers loading bananas, and men reading “El Machete”. And while she made several luscious images of isolated floral specimens during these years, these Modernist views are balanced by those same aesthetics as applied to seas of workers in wide brimmed sombreros and an elegant still life combining a sickle, a bandolier, and a guitar.

The show ends a few years later, with standout Modernist compositions of a typewriter and stacks of sugar cane by Modotti, then bookended by two portraits of Frida Kahlo (and Diego Rivera) made by Weston in 1931. At this point, the Mexican journey for both artists ends, the shortness of its length more than matched by the intensity and quality of the work made during that time.

The important art historical takeaways from an exhibit like this one are several. First, it’s clear that for Weston, Mexico was a crucial pivot point in his career, where his aesthetics turned more closely towards the pared down clarity and abstraction of Modernism; both in the sun blasted heat or the cool reserve of the studio, his eye became increasingly controlled and precise. Second, Modotti was not only a muse or an apprentice, she quickly established herself as a master photographer in her own right, and her images of Mexican life actually have more consistent engagement and personal empathy than Weston’s. For both, as seen here, there’s a very palpable sense of risk taking, adventure, and change, and that swirl of personal (and collective) awakening comes through again and again in photographs that durably thrum with revolutionary energy.

Collector’s POV: The works by Tina Modottti in this show are priced between $12500 and $200000. Modotti’s prints come up for auction fairly consistently, with a handful of works coming to market seemingly every year. Prices in the last decade have ranged between roughly $2000 and $690000 (in 2019.)

The works by Edward Weston in this show are priced between $12000 and $200000. Weston’s works are ubiquitous at auction, ranging from posthumous prints made by Cole Weston to rare vintage icons. Prices in the last decade have ranged between roughly $2000 and $1071000 (in 2024).

The works by Carlos Romero Orozco are priced at $3500 each.