Contemporary photography has got itself tied in knots, struggling with a definitional crisis that seems intractable – in this new digital age, we can’t seem to agree on which artworks are photographs and which ones aren’t, and this messiness is causing confusion and misunderstanding. In the past, I have tried to employ a clear bright line that said a photograph was an artwork whose end product was a photographic print. It was an ends versus means kind of argument; however the artist got there, whatever methods were employed (particularly whether they used a camera or not), if we ultimately stood in front of a physical photographic print, then it was a photograph, plain and simple; if we were looking at a painting, or a sculpture, or a video, then that wasn’t a photograph, as anyone could plainly see. But this kind of simplistic in or out logic has become outdated, made obsolete by the rise of the inkjet printer.

Inkjet printing technology has now become deeply embedded in the art world; it’s not just t-shirts, coffee mugs and mousepads anymore. (For the purposes of this discussion, I’m going to use “inkjet” to encompass all of the digital printing technologies, including archival pigment and other approaches; this is not to underplay their artistic nuances or the real importance of those details to artists, but simply to make the analysis clearer.)Extremely high quality, commercial scale printers have become physically wide enough (nearly 4 feet in some cases) to handle large artworks (especially in pieces), and the underlying substrate has quickly moved to support not only variants of photographic paper but canvas, linen, vinyl, and an astonishing array of even more arcane materials like wood, leather, wool, and plastic; the advent of 3D printing will take this kind of repeatable, mechanical processing into a whole new realm. Not surprisingly, a wide variety of artists, who might previously have identified themselves as painters, sculptors, textile designers, or photographers have embraced these technical advancements and used them to generate new and innovative artworks, and this has only just begun.

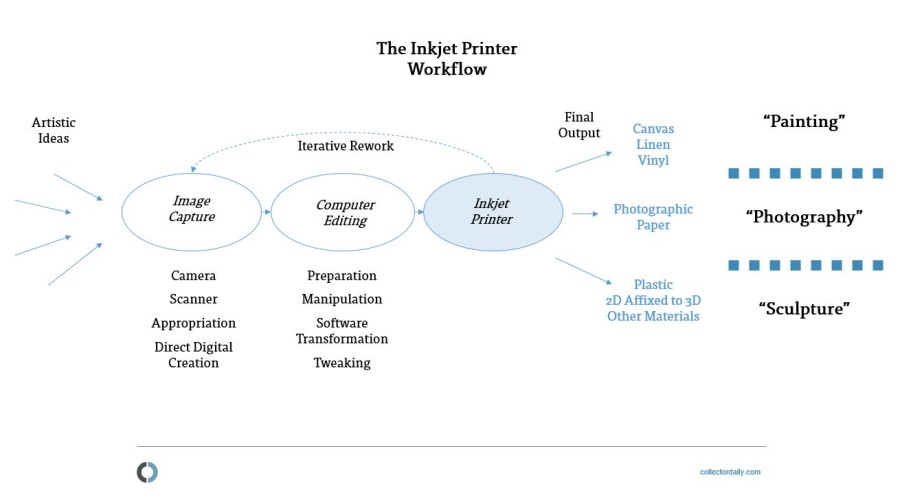

The diagram below is a simplified view of the process of creating an inkjet printer artwork, a flowchart of the steps that begins with artistic ideas and ends with outputs in various media, often with multiple looping or recursive steps in between. The important point here is that regardless of whether we start with a camera, a scan of a pastel drawing, or a native, in situ digital creation and end with a “painting”, a “photograph”, or a “sculpture”, the interior, under the hood image management process is relatively similar.

For those coming from an analog photography mindset (and who have recently moved to digital), this diagram will seem altogether obvious, the substitution of digital for analog and “dry” darkroom for wet already well internalized. But for other artists from adjacent disciplines adopting (or thinking of trying) this new process, the implications are more transformational. While both painting and sculpture long ago incorporated lithography and screen printing into their aesthetic vocabularies, this new workflow is much more deeply rooted in photographic thinking – it’s still a capture, process, output progression, but now it’s readily applicable to other artistic disciplines. By embracing this approach, adjacent artists are not only bringing true mechanized reproducibility to the table (a painting or sculpture need no longer be unique), they are also opening the door to the easy incorporation of all kinds of available image material that was previously somewhat difficult to absorb.

Lest this analysis seem overly reductive and predeterministic, this contemporary inkjet revolution actually frees up artists to go in all kinds of new and different directions – the artist’s role has become even more open ended. While the framework might seem rigid, it has opportunities for improvisation, hand crafting, and chance at almost every stage. Like Lucas Samaras’ manipulations of the Polaroid SX-70 developing process, one only need look at the recent success of Wade Guyton’s inkjet paintings to see that the precision and specificity of an inkjet printer can undermined and altered; it some level, it can be played like an electric guitar, with the equivalent of distortions, howls, and reverbs possible with the right physical interventions, glitches, and chance occurrences. More broadly, the power of this framework comes from its openness – the artistic inputs on the left of the diagram are of course infinite, and the intermediate steps and iterative reworking process in between allows for the underlying system to adapted to an astonishing variety of uses.

The two definitional challenges that current photography faces are seen in the works that are output on photographic paper but otherwise employ few (or no) traditionally photographic techniques, and their corollary, those artworks that are steeped in photographic activities, but are ultimately executed in non-photographic materials. Both sets of works are giving us fits, as they don’t fit into any neat box. And the real wildcards are those works that are simultaneously pushing both limits (no cameras and non-traditional materials at the same time).

Let’s consider a few examples. Gerhard Richter’s recent stripe “paintings” started with a scan of one of his squeegeed abstracts, which was then meticulously manipulated via software; the resulting images were ultimately printed out on photographic paper and made supremely glossy via Diasec facemounting, but resolutely called “paintings”. Alfred Leslie’s recent works were created inside digital paint programs – delivered as large scale photographic prints, he calls them “pixel scores” to reinforce the lyric quality of his handmade (but digital) work. Artie Vierkant has played with software generated color gradients and overlapping geometries, outputting them as wall hanging sculptures in thick Sintra. Kelley Walker has brought appropriated pop culture imagery and software effects to end result inkjet paintings, further decorating them with gestural chocolate. And Thomas Ruff’s zycles began with mathematical algorithms, which were then plotted as swirling lines and displayed as painted canvases. This short list is easily expanded, simply by noting those exploration minded artists traveling down the unseen byways of printing on perforated vinyl (see Peter Sutherland in today’s Daybook here), or moldable plastic, or making iterative collages of disparate digital elements, or further unpacking inks, powders, and paints in new ways.

What I think we can conclude is that digital photography is influencing adjacent artistic mediums in ways we hadn’t expected or even considered; the interconnectability of digital imagery is one piece of the puzzle, but we largely had that (in less mutable forms) back in the days of Warhol or Rauschenberg or photocopied zines. What’s different now is that the changing output options of inkjet printing have allowed the encroaching photographic beast to peel off more and more converts, in the process changing, at least on the margin, what it means to be a painter or sculptor. This leaves us with an excitingly murky definition of photography. If I make a pencil drawing, scan it, morph it using software, print it out, draw on it some more, rescan it, and print it out on burlap sacking, how is that a photograph? Maybe it isn’t, but that artwork has been executed using a fundamentally photographic workflow and has more in common with “traditional” photography than we are currently giving it credit for. Read Jerry Saltz’ appropriately gushing review of Wade Guyton’s recent Whitney show (“brave new paintbrush” here), but notice that there isn’t a single mention of photography as any kind of antecedent. I find that surprising. We need to come to better grips with this new inkjet printer world, and realize that photography is expanding so quickly that it is revolutionizing nearby artistic mediums without even being noticed.

What we need now is a robust, engaged discussion (and/or a well curated show, hint hint) of exceptional “photographs” that don’t have a physical endpoint on photographic paper, and an acknowledgement of the growing acceptability of this approach in contemporary art, without getting lost in avoiding the taint of the photographic ghetto. Like an insidious melt river underneath a glacier, this photographically infused inkjet methodology is quietly undermining the foundation of painting and sculpture, and it won’t be long before big icebergs start to fall away. The goal here isn’t some digital for digital’s sake nonsense – that kind of process-centric analysis doesn’t get us anywhere and we’ve all seen it lead nowhere before; I think we need a more careful examination of current hybrid examples to draw the end point definition of “photography” or perhaps we need to introduce some new transmedia art word that encompasses the new results – either way, my bet is that photography will be encroaching further into the jungle of adjacent artistic disciplines that we could have ever imagined.

I think this inkjet workflow revolution lies at the root of 21st century contemporary photography, and its underlying uncertainty and potential are manifesting themselves in the new work of this moment we are seeing in our risk taking galleries. But we find ourselves in a place where the critical thinking is meaningfully lagging the action – we have some fundamental definitional leg work to do to wrap these innovative artistic changes in a more robust analytical framework, and until we embrace what is happening, we will constantly be fighting over where these new “photographs” fit or if they are photographs at all.

You seem to dump all printing as coming out of an inkjet printer and that’s incorrect. There are light jet prints which still use chromogenic paper going through chemistry and coming out a set of rollers. This is the traditional C-print medium, the difference being that with a light jet a laser exposes the paper. These papers have a different substrate and resolve color/tonality differently than inkjet printers. This process can also be used to produce B&W prints either on color paper or on B&W fiber paper. So your diagram would have to have another branch which would be light jet printing on photographic paper.

Also your inkjet to photographic paper line is misleading because inkjet printers do not print on traditional papers which is what your notation suggests. They print on papers made for inkjet printing. Traditional printing is paper interacting with chemistry and inkjet is ink sprayed on to a paper surface. This is probably the locus of some of the dialogue around “photography” being in one domain or another and in some ways makes digital printing seem more like painting. The input for either form of these printing methods can obviously be either film photography scanned or digital capture downloaded or anything scanned or created in a computer since both methods print with a digital file.

You should talk to the guys at Laumont Photographics on 52nd street. Those guys know it all.

I often think that digital capture and ink jet printing is something fundamentally different than what we had previously called photography. It has a different malleability and vastly expanded capabilities and it’s own output. I think your article is useful to point out that we should think through some of these categories and there’s no rush to change things but different processes do have different meanings but nobody has to marry a process. An artist creates art, no matter what form or medium that takes.

I’d suggest that defining photography by the physical form of its end product broadly misses everything that’s unique and interesting about photography.

Even in the 19th century we had a number of non-light-sensitive printing methods that fell under the umbrella of photography: photogravure, rotogravure, gum prints, oil prints. We’ve had transparencies for nearly a hundred years, where arguably the final product is a projection, and not a print at all. You may not want to get into a Socratic argument about fundamental differences between a projected image and an image on a screen.

Here’s an unoriginal thought on the true nature of photography: it has to do with how the image was captured. It has to do with light. And it has to do with semiotics. A photographic image is a semiotically similar to a fingerprint, in that it not just resembles the thing it points to, but was actually caused by it. This makes a photograph an indexical sign, as opposed to a painting, which has no causal link to what it depicts. A photo-realistic painting of a person would be considered an iconic sign, because it refers by resemblance, not causation.

A photograph can of course be both. But it may not. And we have always had images that poke at the boundaries. What about manipulation in the darkroom, the studio, the computer? To what degree has that causal link been broken?

This is a very big topic, and much has been written on it. But I think you’ll find it a deeper and more interesting well than worrying about the chemical nature of a print.

Well said!

Thank-you for this perceptive description of a change in artistic direction.