JTF (just the facts): A total of 43 photographs and sculptural works, variously framed/displayed, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space and the office area. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- Auguste Rodin: 1 bronze, 1884/cast 1910-1918, sized 20x26x12 inches, in edition of 32; 1 carbon print mounted to board (by Jacques Ernest Bulloz), c1906, sized roughly 10×14 inches; 1 gelatin silver print (by Jacques Ernest Bulloz), 1900, sized roughly 12×15 inches

- Barbara Morgan: 1 gelatin silver print mounted to board, 1943/c1943, sized roughly 16×19 inches; 1 gelatin silver print, 1940/1980s, sized 11×14 inches

- Aaron Siskind: 1 set of 4 gelatin silver prints, 1956-1960, each sized roughly 11×10 inches; 1 gelatin silver exhibition print flush mounted to board with wooden stretcher, 1954, sized roughly 50×40 inches; 4 gelatin silver prints mounted on masonite with original cleats, c1940s/c1950s, 1948, c1940s, sized roughly 9×6, 9×4, 9×7 inches; 1 gelatin silver print mounted on masonite, 1950, sized roughly 5×9 inches

- Imogen Cunningham: 1 gelatin silver print, 1933, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- David Smith: 1 gelatin silver print, 1951, sized 8×10 inches; 1 accordion book with gelatin silver prints, 1948-1949, sized roughly 8×8 inches; 1 steel, cast iron, bronze, 1953, sized roughly 25x6x5 inches

- Frederick Sommer: 1 gelatin silver print mounted to board, 1946, sized roughly 10×8 inches

- Man Ray: 1 assemblage of croupier’s rake on bronze base, 1955, sized roughly 30x4x4 inched, in an edition of 10, with 1 gelatin silver print, 1955/c1960s, sized 9×3 inches; 1 metal spring, bronze ball, and ink on cigar box, c1961, sized 12x7x8 inches, with 1 gelatin silver print, c1961, sized roughly 7×5 inches; 1 gelatin silver print mounted in camera shutter, c1950, sized roughly 5x5x1 inches; 1 gelatin silver print, 1929/c1965-1966, sized roughly 21×16 inches; 1 photomontage, 1923-1924, sized roughly 7×4 inches

- Constantin Brâncuși: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1923, c1934, sized roughly 11×8, 10×7 inches; 1 gelatin silver print mounted on board, 1919/c1923, sized roughly 16×8 inches

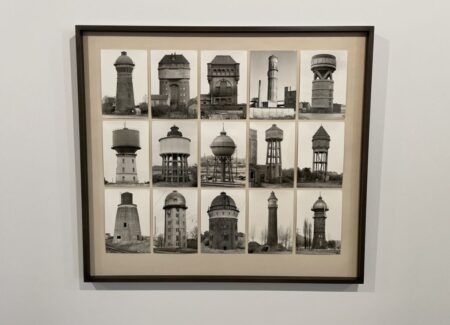

- Bernd and Hilla Becher: 1 set of 15 gelatin silver prints, 1959-1969/1970s, sized roughly 29×34 inches overall

- Karl Blossfeldt: 1 gelatin silver print, 1915-1925, sized roughly 12×9 inches

- Edward Weston: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1924, 1936, sized roughly 8×7, 8×10 inches; 1 palladium print, 1925, sized roughly 10×7 inches

- Bill Brandt: 1 gelatin silver print, 1956, sized roughly 9×8 inches

- André Kertész: 4 SX-70 Polaroid prints, 1979, sized roughly 4×4 inches; 1 gelatin silver print, 1930, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- Josef Sudek: 1 pigment print, 1951, sized roughly 9×7 inches

- Henry Moore: 1 bronze, 1930, sized roughly 6x8x3 inches; 1 gelatin silver print, 1934, sized roughly 10×8 inches; 1 gelatin silver print mounted to board, 1956, sized roughly 16×20 inches; 1 bronze, 1957/c1976, sized roughly 8x5x6 inches; 1 bronze, 1945, sized roughly 5x8x4 inches

- Robert Mapplethorpe: 1 bromoil gelatin silver print, 1981, sized 40×30 inches

Comments/Context: In the life of a gallery, one of the potential moments for a transition in strategy comes with a change of physical space. A new location, a new arrangement of offices, and a new layout of storage and display spaces can catalyze a subtle shift in mission, direction, or staffing, allowing the gallery to both leave some things behind and step into its new reality with fresh eyes and renewed energy.

For Bruce Silverstein, the move from one floor to another in the same Chelsea building might not seem revolutionary, but the new space is a significant upgrade in size and styling from his more intimate previous rooms. Along with the move upstairs, the gallery has taken the opportunity to widen its artistic mandate a bit, extending its interests from a specialized focus on photography to include the varied interactions between photography and other mediums. With more middle of the room space to fill in this new gallery, we can expect to see more connections between photographers (both classic and contemporary) and painters, sculptors, filmmakers, installations artists, and performers of various types, pulling photography out of its narrow silo and into more consistent dialogue with other artistic approaches.

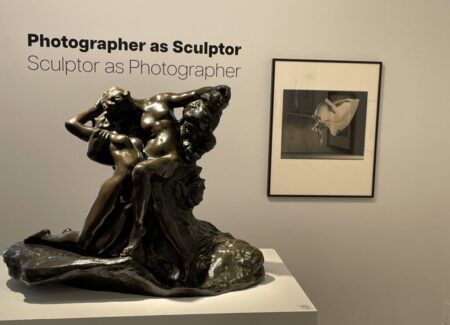

The inaugural show in the new space overtly signals this broadening of scope. “Photographer as Sculptor, Sculptor as Photographer” thoughtfully brings masterworks from various 20th century photographers who were particularly interested in form and structure into conversation with the work of a handful of sculptors who used photography to activate and reimagine their constructions. The result is a lively convergence of ideas and approaches, with plenty of plinths that bring the action off the walls and lots of visual echoes to discover, smartly mixing photographers thinking sculpturally and sculptors seeing with a camera.

Curatorially, care has been applied to the small rhythms of this show, creating pockets of works that speak to each other. One area brings together studies of bodies in twisting motion, including a bronze sculpture and photographs of sculpture by Auguste Rodin, dance photographs by Barbara Morgan, and airborne images by Aaron Siskind. Each of the artists is considering bodies in three dimensional space, with Rodin creating specific viewing angles to amplify the fluidity of his bending forms, and Morgan and Siskind capturing the related energy of active motion, in form of elegant kicks, sweeps, and floating falls seen from underneath.

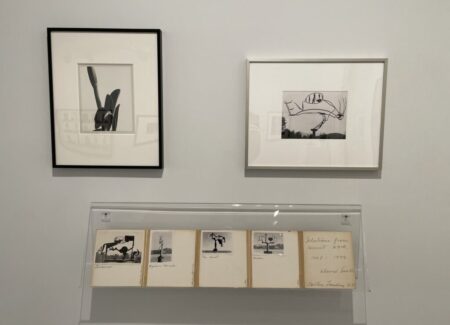

In another corner, a David Smith metal sculpture (made in 1953) hangs from the ceiling, creating an array of formal shadows on the nearby walls. It is paired with a rare book maquette filled with a selection of photographs made by Smith of his sculptures set against outdoor backdrops. His dark silhouettes are then matched by a classic Imogen Cunningham photograph of an amaryllis (from the 1930s) which plays with similar contrasts of light and dark, creating an unexpected aesthetic meeting of the minds.

The duality of the photography/sculpture thesis is given more heft by a run of three powerhouse proofs: Man Ray, Constantin Brâncuși, and Aaron Siskind. The gallery has unearthed two superlative Man Ray examples, where a Man Ray sculpture is paired with a vintage Man Ray photograph of the same sculpture, offering a clear sense of how he was interpreting and re-imagining one with the other. Sadly, there is no similarly astonishing 3D/2D Brâncuși pairing, but the trio of Brâncuși photographs included here shows how he used light and motion to deliberately rethink his sculptures via photography. And in the case of Siskind, we move out onto a plinth, where photographic objects capturing the abstract lines of seaweed and wire take up space, their tactile gestures enhanced by the physicality of their presentation.

The show then moves back to the wall, with a run of works by 20th century master photographers whose eye for their chosen subject turned it into something resolutely sculptural. The powerhouse hit parade includes water towers (by Bernd and Hilla Becher, who called them “anonymous sculptures”), plant forms (by Karl Blossfeldt and Edward Weston), and female nudes (by Weston again and Bill Brandt), each enlarged, cropped, or abstracted to the point that its shapes (and negative space) become primary, thereby turning the photographic observation of the subject matter into a flattened formal exercise.

The last mini-section of the show brings the British sculptor Henry Moore into the conversation, via three small sculptures and two photographs made by Moore of similar works. Again, the photographs show the sculptor reimagining the spatial dynamics of his own art, rethinking how highlights and shadows change the moods of the pieces. Perhaps the most inspired pairing in this show starts with a photograph Moore made of three abstract forms (in 1934), the edges of the stone objects softened into planes, holes and rounds. This has been elegantly paired with a Josef Sudek still life (from 1951), where faceted water glasses and eggs create a surprising compositional back-and-forth with the Moore image. It’s a wildly sui generis kind of connection, that feels strangely right on the mark.

In many ways, this show feels like the placing down of a marker or the restating of first principles for this gallery – a message that this is the kind of thing we are interested in and will deliver going forward. Given the rarities collected here, and the thoughtfulness with which they have been sequenced and arranged, the evolution of the gallery’s focus feels altogether natural. It’s growing outward from its center of strength and challenging itself to make inspired links out beyond its comfort zone. I like that message – it says we’re continuing to celebrate the photographic connoisseurship we have previously worked hard to build, but we’re refreshing it with artistic ideas that won’t always be comfortable or predictable. A Rodin sculpture intelligently included in the center of a photography exhibit? That’s an idea we haven’t seen too often before, and just might get a few collectors (and institutions for that matter) thinking in new ways.

Collector’s POV: Given the wide range of work on view in this group show, we will forego our usual artist by artist price discussion; in general, the works are priced between $7500 and POR, with the Rodin sculpture unsurprisingly at the top of that range.