JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by Stanley/Barker (here). Hardcover with debossed spine, 290 x 250 cm, 120 pages, with 55 monochrome images. Includes an essay by Albert Mobilio. Designed by The Entente. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: If you draw a blank at the name Paul McDonough, it’s more a reflection of zeitgeist than skill. The type of photography at which he excelled, black and white candids found afoot with a Leica and a pocket full of Tri-X, has long since faded since its seventies heyday. Its obsolescence has pulled many talented practitioners into the foggy realms. Simpson Kalisher, anyone? Jonathan Brand? They are far below the radar now, along with contemporaries Robert D’Assandro, Mark Chester, Michael Spano, Enrico Natali, Flo Fox, and countless others. McDonough might too have faded into obscurity if not for the dedicated efforts of admirers to keep his legacy afloat.

His 2010 monograph New York Photographs 1968-1978 was an initial stride toward recognition. McDonough was in his seventies by this point, but I’d never heard of him. After being bowled over by this book, I made it my mission to track down whatever I could on him. But there wasn’t much. He’d grown up in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and studied painting in Boston. After a move to New York in 1967, he’d fallen in with Garry Winogrand’s circle. Under his wing, the deeper plunge down Manhattan’s rabbit hole came naturally, its crowded corners gushing photographic permutations. Like many street photographers, he cobbled a subsequent career out of teaching (Yale, Pratt, Parsons, Fordham, Cooper Union), grants (NEA and Guggenheim), and freelance work, all activities in service to the primary goal: prowling sidewalks. But beyond the debut monograph, McDonough’s archive remained largely latent.

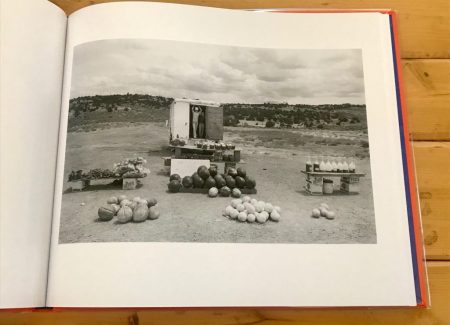

Sasha Wolf’s curation Sight Seeing (an exhibition in 2013, reviewed by Collector Daily here, and a book in 2014, reviewed by me here) introduced another batch into public discourse. Sight Seeing tracked McDonough out of his comfy New York environs, as he embarked on a series of cross-country car trips in the 1970s. The candid groupings and quirky nooks he found out west bore some similarity to Manhattan’s thoroughfares, but a less confined version. Under the spell of open road, McDonough’s innate curiosity bubbled to the surface. He was a born explorer, a car borne flaneur, and a crack sharpshooter regardless of locale. “This show broadens our view of McDonough, exposing a side of his work that we hadn’t seen before,” observed Collector Daily, before hinting at future possibilities: “Step by step, exhibit by exhibit, we’re working our way forward in time, his archive proving richer and more varied with every successive discovery.”

Eight years later comes the next (and potentially final?) career chapter. McDonough’s new book Headed West picks up where Sight Seeing left off, further mining material from his western adventures. Viewed in broad thematic strokes, it doesn’t expand his oeuvre much beyond its predecessor. But it does offer a measure of career resolution, boasting numerous winners in the process. The edit this time is by McDonough, with help from his wife and friend Andrew Borowiec, and spurred by the hapless drumbeat of McDonough’s Alzheimer’s. Their collective aim was to make this book while McDonough was still thinking clearly about his photographs. In Stanley/Barker, they found a publisher who knows a thing or two about recovered memories.

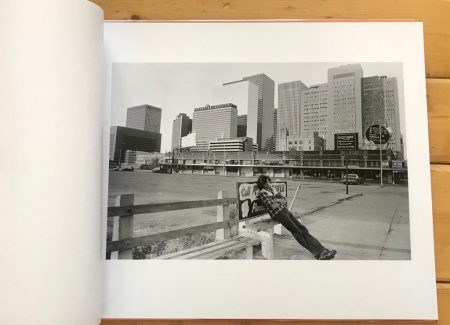

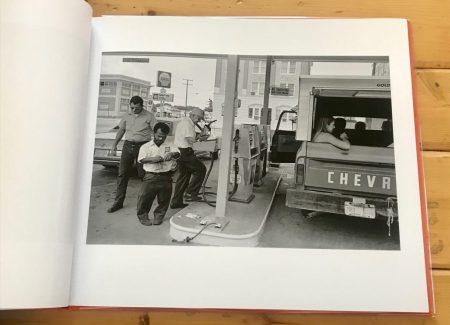

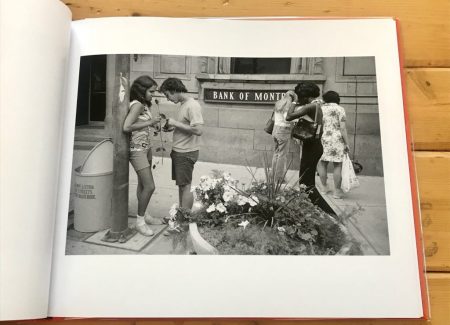

The first photograph in the book might be a proxy for McDonough tapping into the subconscious. It shows a man enjoying a moment of quiet meditation on a park bench in Houston, 1975. The city’s skyline behind him beckons with photographic potential, but the subject is content for now to dream inward. The scene is a portent of things to come. Although this is nominally a book of the open road, its photos primarily depict urban locations. McDonough made photo stops in New Orleans, Toronto, Austin, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Portland (where his brother lived), among other places. Technically all are west of New York. But some conjure the frontier better than others.

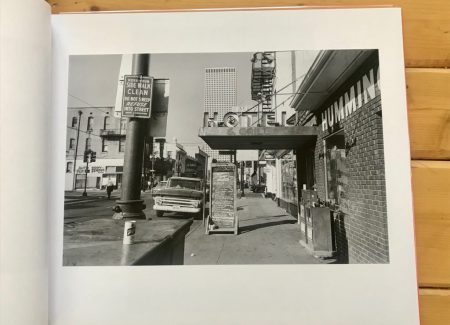

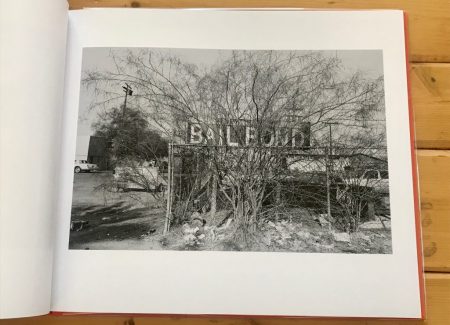

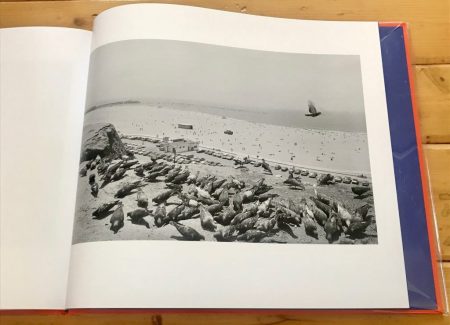

Judging by his pictures, McDonough beelined between these cities, bypassing the wide landscapes in between. Leave it to road-tripping contemporaries like Wessel, Friedlander, and Shore to document exurbs, vistas, and other cracks in the social firmament. Even Winogrand found brief muse in White Sands. But no such material appears here, apart from a few decrepit billboards. McDonough preferred bustle, tending to corners and promenades where pedestrian flows might intersect.

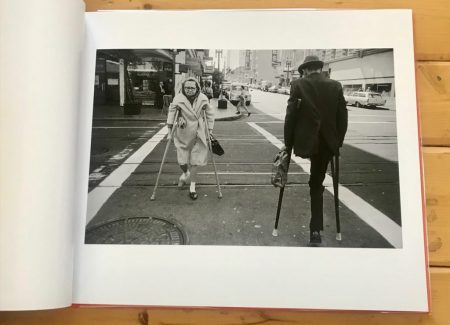

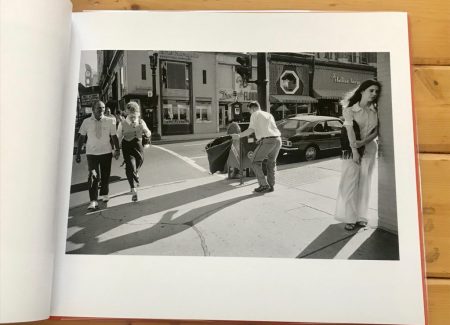

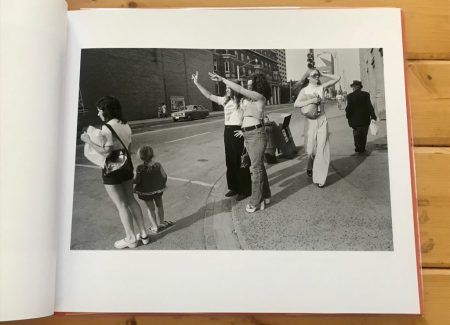

If he applied a Manhattan outlook to flyover country, that’s because his central concern was people—not so much their inner lives but how they expressed themselves physically to the outside. Strangers have inscrutable intentions. Their actions are fickle and fleeting, and aligning fluid behaviors into cohesive arrangements is a stiff challenge. McDonough was more than up to it. In fact I’d surmise it was his chief motivation. “Part of both the pleasure and the frustration [of photography] is not knowing just what you’re going to encounter and when,” he once told an interviewer. “You have to have the belief that you will see something on the contact sheet later that rewards your faith.” When asked, “Do you believe in the idea of happenstance with your work?” McDonough’s explanation was matter of fact: “Yes, I am entirely dependent on it.”

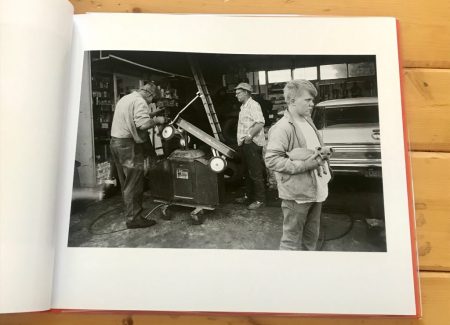

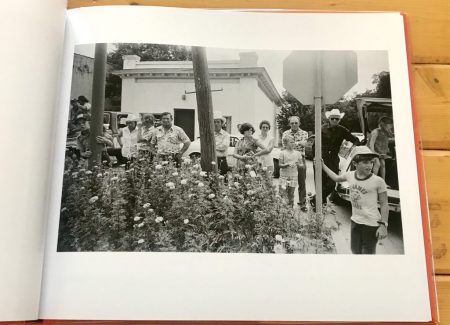

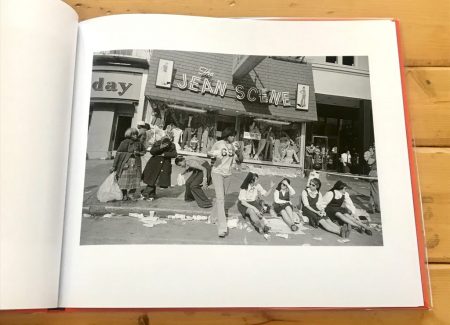

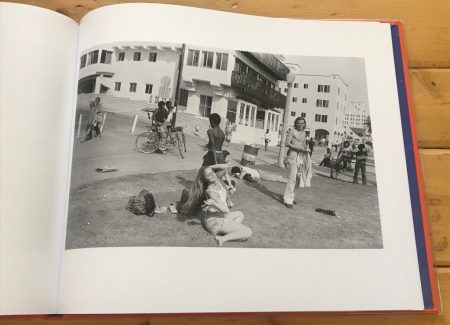

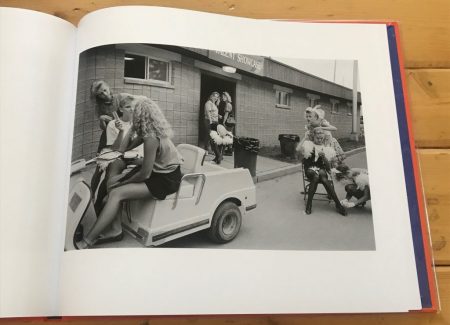

Chance coalescence was a lure, as were the questions his improbable exposures raised in the mind of the viewer. “His pictures describe the space between the truth and the fiction of public life,” wrote Hilton Als about Sight Seeing. It seems Headed West has only sharpened the verdict. Photographs of Texas spectators arranged into precise formation, garage workers jigsawed with their tools into still life, and a Portland street corner spilling over with light and pedestrians are so perfect they might feature actors on a stage. All were found in passing.

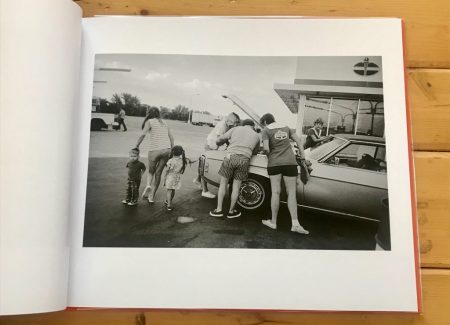

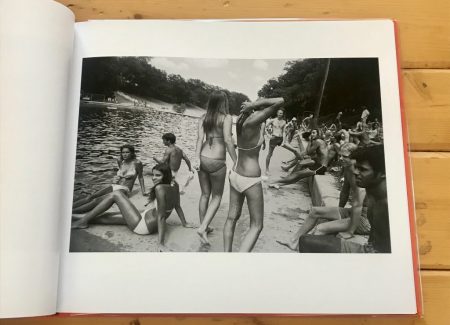

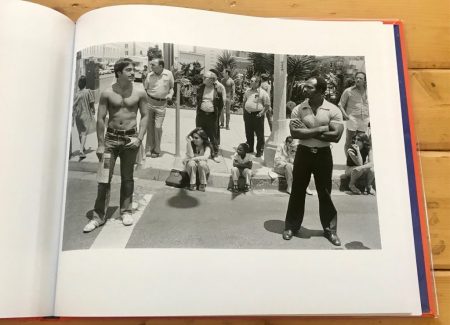

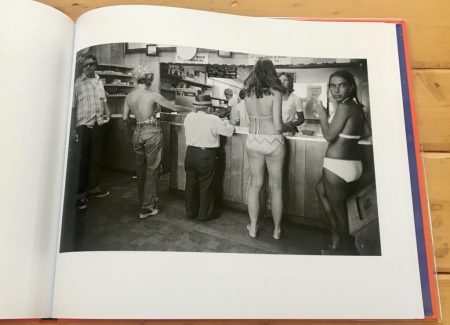

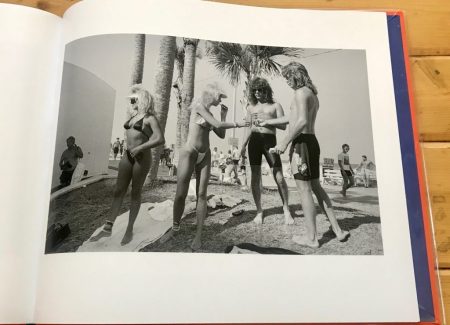

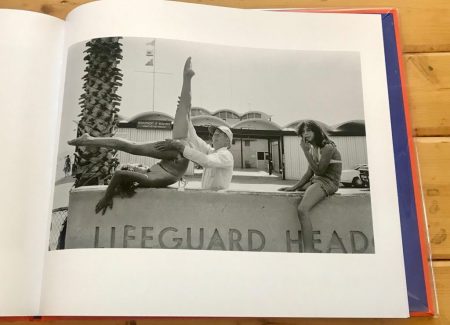

Many of McDonough’s trips happened in summer, between teaching duties. Headed West is stocked with sunbaked leisure scenes and plenty of bare skin. Scant wardrobes may simply indicate warm weather. But there are enough bikinis, bare chested men, and water play in this book to pry at deeper currents: body posturing, physical attraction, and exhibitionism. A photograph from Venice Beach, 1979, seems to capture a momentary lover’s triangle. A photo of scantily clad swimmers in Austin, 1974, has voyeuristic undertones. Winogrand was in Austin at this point and it’s likely they spent time together. Perhaps his unabashed leering influenced McDonough? In any case the swimmers are framed in Winograndian fashion, against a cockeyed horizon.

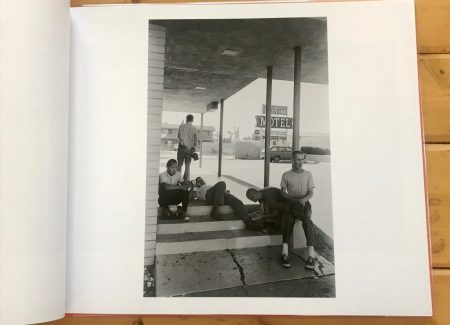

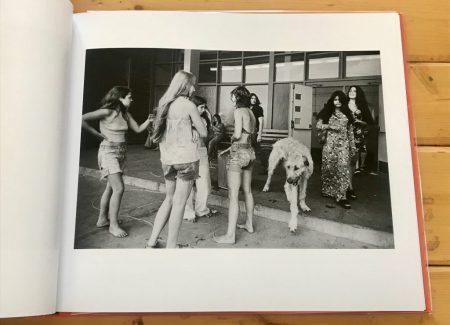

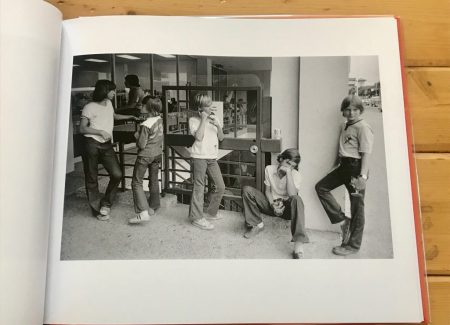

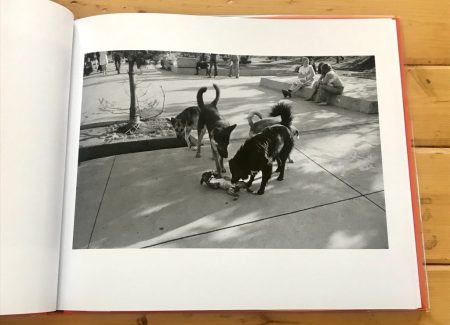

When he could, McDonough linked humans (and the occasional dog) into single file across the frame like silverware at a table setting. A photograph from San Bernardino, 1977, is typical, with men posed in unison near some steps. Another photo from Ohio, 1971, marshals two mechanics into formation with a waiting family. A picture from Austin, 1974, captures a cluster of five boys. They’re spaced so evenly they might be cordoned by invisible walls. A shot from Mardi Gras, 1975, separates a crowd of eight women into precise vertical octets. McDonough’s inner octogenarian must be smiling.

For an extra challenge, he liked to bookend many of these human chains with dreamy faces at their edges, a smiling boy perhaps, or a wistful teen. McDonough “infuse[d] quotidian scenes…with Caravaggio-like drama,” writes Albert Mobilio in the afterword. That comparison may be a stretch, but few photographers were as skilled at choreographing bystanders into chorus lines. Tony Ray-Jones and Alex Webb come to mind. Perhaps Helen Levitt or Viktor Kolář are comparable, or Winogrand on a good day. After that the trail grows faint.

This approach—found moments with the staged precision of fabrications—prizes individual candids over thematic conceits. Pictures come fitfully, at their own pace. Contact sheets always tantalize with the promise of undiscovered nuggets. Headed West unearths a few dozen first rate gems, and even includes a couple old favorites from Sight Seeing.

Sequencing this sort of work into book form can be troublesome, since the pictures do not fall neatly into projects. Rather than X book, then Y, then Z, they tend to arrive as an amorphous time dump, e.g. New York Photographs, 1968-1978. These are choppy curatorial waters, and Headed West attempts to navigate them with a classic device: the road trip. But it’s not clear to me the fit is seamless.

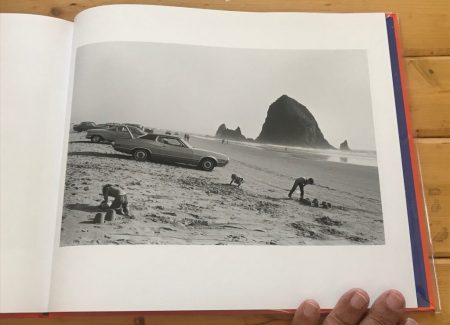

Nevertheless Headed West takes a stab at it. The title imposes a narrative arc, as does its oddly flipped sequence on the front and rear covers (“West Headed”, as if seen in the rearview). The journey west achieves some closure at the Pacific Ocean, with the book’s final few images of Cannon Beach, 1971 (where “the great American road trip has run out of road,” according to The Guardian’s Tim Adams), and Santa Monica, 1972. It all works out fine in the end, but the plot feels forced. McDonough’s photos were less about any particular destination than the journey itself. The only through storyline was observation. For fans of that approach, and of pure candids captured in the wild, this latest offering is a treat. Hopefully it will keep McDonough’s name on the radar a while longer.

Collector’s POV: Paul McDonough is represented by Sasha Wolf Projects in New York (here). Gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

I was so moved by this piece; thank you, Blake Andrews for your discerning eye and eloquent expression.