JTF (just the facts): Published in 2014 by Editorial Mal de Ojo (no website). French fold binding with cardboard covers, 226 pages, with 115 black and white and 16 color photographs (with additional thumbnail index). The photographs were made between 1954 and 2014. Includes texts in Spanish/English by Victoria de Stefano, Sagrario Berti, and the artist, along with quotes/captions from the 1999 Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. The book was designed by Ricardo Báez. Edition of 250. (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: When a talented photographer consistently points his or her camera at a notable city and tries to show us its complex, shifting nature, we often find ourselves adrift in a visual mix of nostalgia and hope – we aren’t surprised when the new roughly cannibalizes the old, but it leaves us both justifiably excited by the future and a bit sad about the good old days that have been left behind. Across the history of photography, truly great long term projects have shown us the changing faces of New York, Paris, London, Tokyo, and other major urban centers (think Marville, Atget, and Abbott just to start), and we have watched as familiar neighborhoods have been radically and permanently transformed by wave after wave of active and deliberate modernization. When these pictures are gathered together as grand sets, we can certainly appreciate their obvious documentary and historical value, but we can also begin to identify the tracks that mark the point of view of the artist coming through – regardless of the location, we’re not just being shown a parade of buildings, sidewalks, and people, but feeling the pulse of a particular city through a very specific set of eyes.

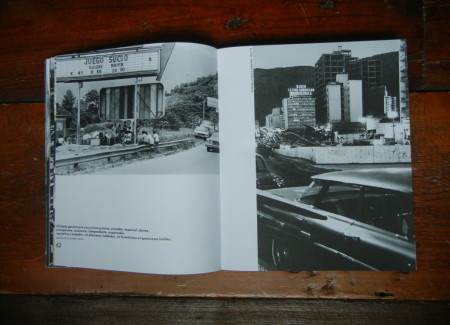

Paolo Gasparini’s undeniably brilliant sixty year portrait of Caracas, Venezuela, doesn’t travel the common pathways we have come to expect from such projects. For the most part, he’s not shown us identifiable landmarks and famous architecture, local festivals and representative citizens, or even quaint storefronts and vernacular traditions, at least as central subjects. His goal doesn’t seem to have been meticulous categorization or anthropological study, nor has the edit of his vast photographic archive been tilted by after the fact reinterpretation in search of evidence of sepia toned bygone ages.

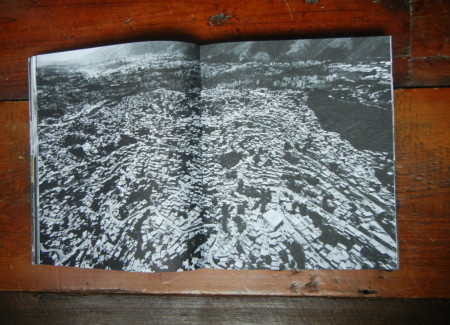

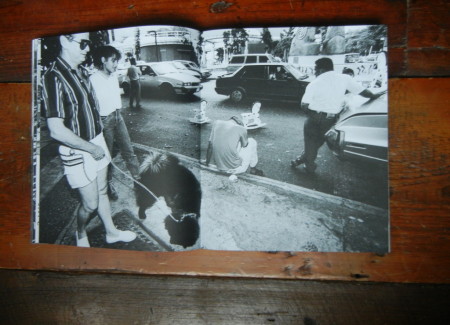

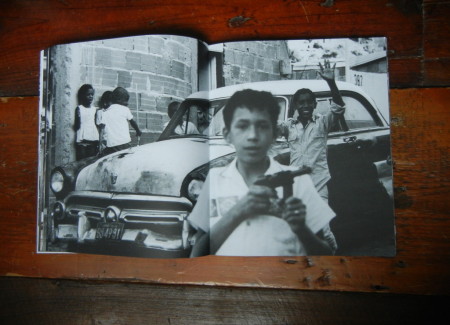

Instead, Gasparini has given us a dizzying, messy Caracas, rich in overt contradictions, despairing decay, and self destruction, a place that verifiably seethes in his poetic pictures. Time and again, his photographs are built on contrasts, showing us divisions, inconsistencies, and everyday travesties, and leaving us feeling estranged and restless, shaking our heads at the dislocations that have filled its streets for decades.

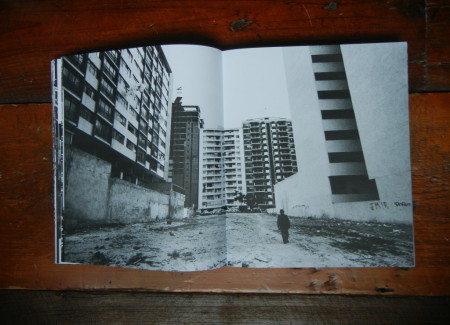

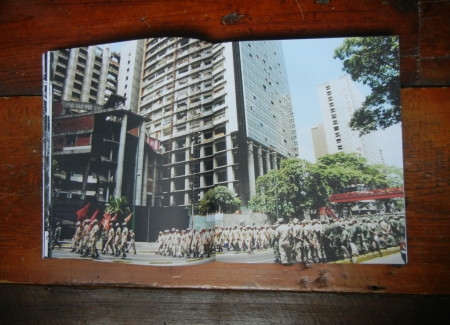

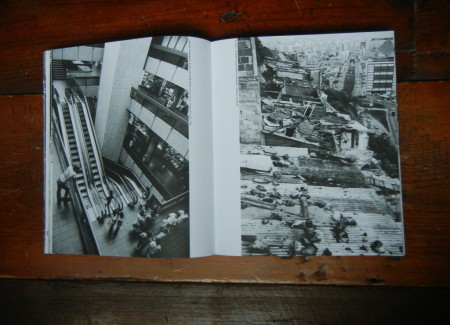

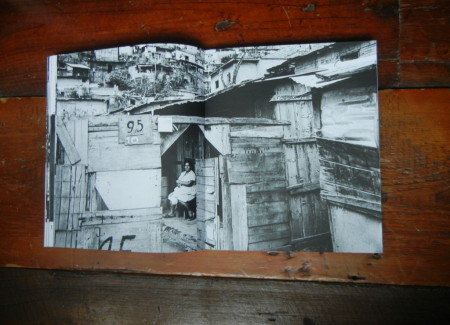

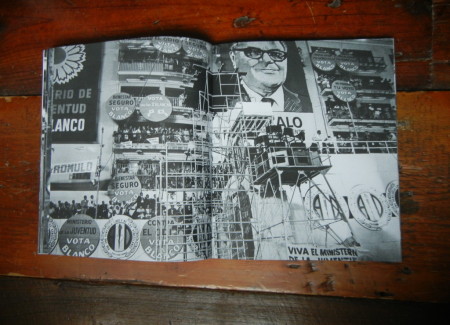

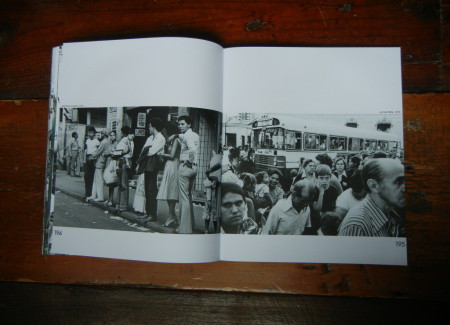

If there is a central visual theme to Gasparini’s energetic photographs of Caracas, it is the deeply rooted separation of rich and poor, and he often uses architecture as a metaphor for this contrast. Broad boulevards and highways lead to dense slums, towering steel and glass skyscrapers are guarded by armed military units, and fancy shopping malls abut abject poverty, with families huddling in hovels or vacant lots right next to the soaring (and often unfinished) buildings. Gasparini intersperses these images with selected quotes from the Constitution, reminding us of the egalitarian ideals of work for all, equality, transparent justice, and a nationally controlled economy; sequenced next to images of long lines in the streets, political protests, civil rights abuses, and crumbling neighborhoods, it’s hard not to feel the ironic sting of his not-so-indirect indictment of those in power. In many ways, his pictures are about a city that has repeatedly failed its inhabitants.

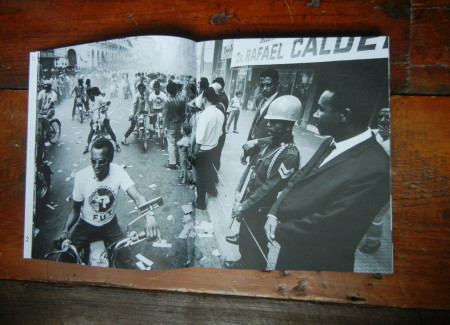

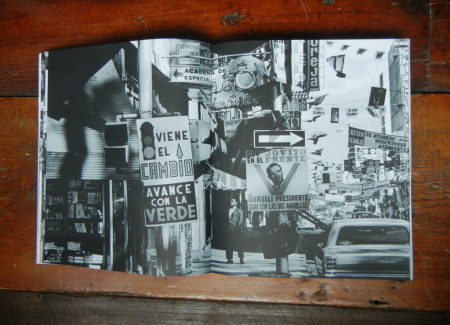

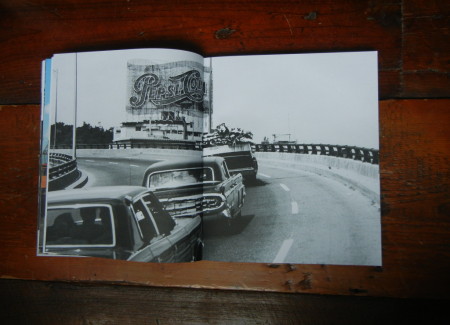

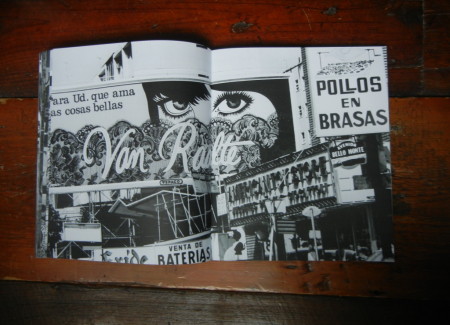

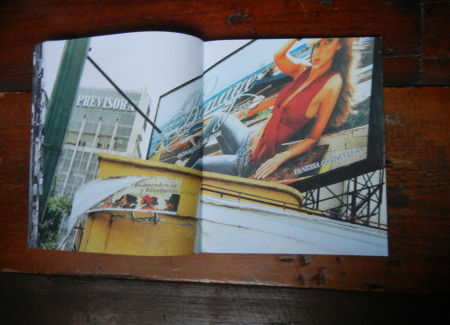

Other images capture the tense cacophony of the streets, where billboards and advertising shout at passersby in deafening layers and traffic piles up in dense thickets of tailfins and shiny hoods. Political rallies and teetering unrest are never far from view, as are guns, in the form of stoic police and army personnel parading or nervously keeping the peace. Trash fills up fountains, kids feed squirrels, and funeral processions carry coffins toward Pepsi-Cola signs – and when the military leaders finally come out in their dress finery, nothing could look more ridiculous. Recent images in color amplify the severity of the twenty first century Chávez-era contrasts further, with seductive come hither luxury models in glossy advertising peering down at a city pockmarked by slow grinding destruction.

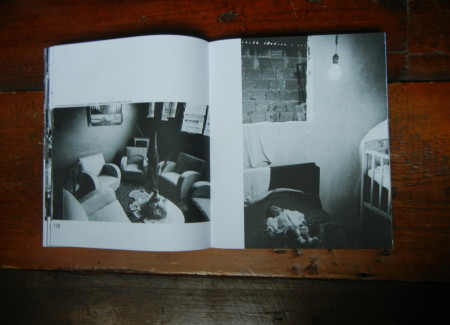

While Gasparini’s photographs do discover a few glimmering moments of hope (a boy selling balloons, a pair of hands furtively held, a ballot box, a determined but peaceful crowd, laughing kids in a traffic jam), that idealism is quickly undercut by nearby images of social optimism unfulfilled or out of reach – an endlessly long public bus, a shimmering bank building paired with a hollowed out blank billboard and a cluster of weary migrants, an art museum put together with a sad open door mortuary (complete with casket), a sleek leather seating area placed next to an unattended baby under a bare lightbulb, a poor woman climbing stairs near a dazzling array of cool sunglasses. One Gabriel Garcia Marquez quote early in the book calls the city “unhappy Caracas”, and as Gasparini’s images pile up, it’s hard not to agree with that conclusion.

In the hands of a lesser photographer, this kind of critical urban portrait laced with political undercurrents might have turned into a shrill discouraging screed, but it’s a testament to Gasparini’s enduring talent that across some six decades of work, his eye for compositional complexity and grace never wanes; even though some of the subject matter can be quietly bleak and disheartening, the pictures keep us looking for secondary and tertiary connections that we may have missed the first time through. Gasparaini’s Caracas is vibrantly challenging, and not without subtle resiliency; with all its visible and invisible flaws and its stubbornly intractable problems, it’s still a place that resonates with authentic life and energy.

Collector’s POV: Paolo Gasparini is represented by Toluca Fine Art in Paris (here). His prints have very little secondary market history in Europe/America, so international gallery retail likely remains a the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

As for the book itself, since the publisher of this photobook does not appear to have a website, I can only offer that I acquired the book from Anticuaria Poema 20 (from Buenos Aires, Facebook page here) while at Paris Photo; it is unclear whether they have any additional copies available. As a footnote, I think that the limited print run (250 copies) and expensive price ($400) of this volume will undeniably choke off the number of people who ultimately see and enjoy this superlative photobook (especially here in the US). I realize that we are in an age of artisanal publishing, but this is a photobook that could have been (and still might be) highly and durably influential if it could find a wider audience. We need to see much more work from South American leaders like Gasparini, and it is my hope that by featuring Karakarakas here, we can spark some persistent souls to go looking for this thoughtful artistic statement, even though such a search will likely seem daunting/annoying from the get go. I know that advocating for such a book has a ring of unfairness (why write about a book that almost no one will be able to acquire?), but I think its artistic merits outweigh the obvious challenges of procuring a copy.