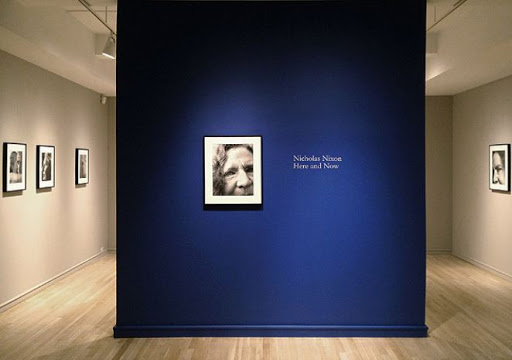

JTF (just the facts): A total of 25 black and white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung against blue and almond colored walls in the entry and two main gallery rooms. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, made from negatives taken in 2011 and 2012. The prints are sized either 11×14 (contact prints) or 16×20 (enlargements) and are available in editions of 10. (No photography is allowed in the galleries, so the installation shots at right are via the Pace/MacGill website.)

JTF (just the facts): A total of 25 black and white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung against blue and almond colored walls in the entry and two main gallery rooms. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, made from negatives taken in 2011 and 2012. The prints are sized either 11×14 (contact prints) or 16×20 (enlargements) and are available in editions of 10. (No photography is allowed in the galleries, so the installation shots at right are via the Pace/MacGill website.)

Comments/Context: Nicholas Nixon’s newest photographs are measured and deliberate, slowed down to the point where attentiveness can overcome everyday distraction. They express interest in the cycle of life, from babies to centenarians, and consider the wearying effects of aging with warmth, curiosity, and affection. They are evidence of a photographer confident in his craft and unhesitant to contemplate the changing stages of his life.

In his previous show, Nixon had already begun to turn the camera on himself, making fragmented self-portraits of his rugged, bearded face. New images take that idea one step further, bringing his wife Bebe into the frame. Up-close pairs of eyes and mouths, the photographer’s bristly whiskers pushing against her skin, his face buried in her long hair, the pictures revel in personal detail. More importantly, they deftly capture a sense of shared intimacy, of genuine caring and closeness built over a lifetime. They function equally well as masterful exercises in photographic texture and as love letters.

In his previous show, Nixon had already begun to turn the camera on himself, making fragmented self-portraits of his rugged, bearded face. New images take that idea one step further, bringing his wife Bebe into the frame. Up-close pairs of eyes and mouths, the photographer’s bristly whiskers pushing against her skin, his face buried in her long hair, the pictures revel in personal detail. More importantly, they deftly capture a sense of shared intimacy, of genuine caring and closeness built over a lifetime. They function equally well as masterful exercises in photographic texture and as love letters.

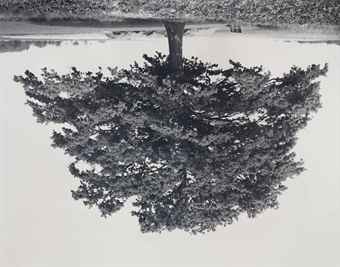

Nixon’s images of mothers and their babies, flanked by centenarians and their loved ones (wives, husbands, sons, and daughters), center on the contrast of young and old, the opposite ends of the human spectrum. These photographs are all about embrace, about touching, holding, hugging, and supporting with the kind of fondness and emotion that is impossible to fake. In a certain way, both sets of images feel a little like commissioned portraits, but they are executed with such grace and good will that is hard not to admire them. The other images in the show capture humble nature scenes from Massachusetts and France, snowscapes and apple trees, meadows of long grasses and hollyhocks in bloom. They are quietly observant, catching and capturing the often overlooked details of changing seasons.

As he ages, Nixon’s work is moving farther and farther away from the conceptual fastidiousness and the art school irony that is now so prevalent in contemporary photography. It’s as if that stuff couldn’t matter less when compared to the nuanced questions of life, of the passing of time and the maturing of love. His pictures are nurturing, and thoughtful, and subdued in a way that is entirely out of step with the whims of fashion. Their gentle authenticity is refreshing and encouraging, like one of the reassuring caresses shared by his subjects.

As he ages, Nixon’s work is moving farther and farther away from the conceptual fastidiousness and the art school irony that is now so prevalent in contemporary photography. It’s as if that stuff couldn’t matter less when compared to the nuanced questions of life, of the passing of time and the maturing of love. His pictures are nurturing, and thoughtful, and subdued in a way that is entirely out of step with the whims of fashion. Their gentle authenticity is refreshing and encouraging, like one of the reassuring caresses shared by his subjects.