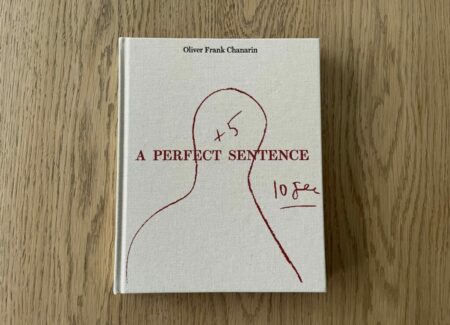

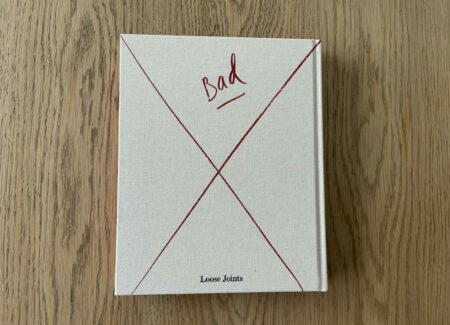

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2023 by Loose Joints (here). Silkscreened debossed hardcover (in three options), 200 x 250 mm, 240 pages with red edging, with 112 color reproductions. Includes an essay by the artist and an image list. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: As Oliver Chanarin tells it, when his multi-decade artistic partnership with Adam Broomberg ended in 2021, it wasn’t entirely clear what he should do next. Perhaps many well meaning cliches were trotted out – a fresh start, a clean break, a new chapter, do the things you’ve always wanted to do, etc. In many ways, as an artistic duo, Broomberg & Chanarin had successfully checked most of the art career boxes – a long inventory of important museum exhibits and gallery shows, several durably memorable projects (particularly War Primer and Holy Bible), and more than a dozen photobook projects, along with various other awards and accolades. But now Chanarin was back on his own, with a proverbial blank slate lying in front of him.

From afar, the answer to Chanarin’s dilemma seems so simple – just get out there and start making photographs again. But in the intervening decades, the context around making photographs, particularly the portraits that Chanarin was most comfortable with and best at, had shifted. Conceptual frameworks and strategies had evolved, and the issues of representation and privacy had become more sophisticated (and thornier) than perhaps they used to be. The result was that he felt a bit lost and paralyzed, saying that he “wasn’t sure how to be a photographer any more.”

Of course, Chanarin isn’t the first successful photographer to work through a mid-career reinvention of himself. Alec Soth recently went through a related process, ultimately coming out the other side with his excellent project A Pound of Pictures (reviewed here). But there is certainly something scary about essentially going back to artistic square one, and re-asking yourself all kinds of questions that you thought you already knew the answers to. And like Soth, Chanarin set out on the road, hoping that wandering encounters with real life might provide the spark of inspiration he was looking for.

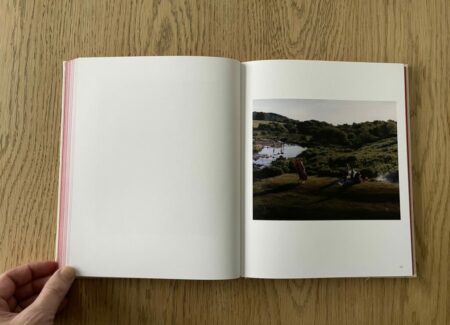

In Chanarin’s case, against a backdrop of self-doubt and inertia, the good news was that he was able to get a total of eight UK arts organizations to help fund his proposed meanderings, which helped him to set up teaching workshops, visits, tours, and other meetings around the country. His photobook A Perfect Sentence is the artistic result of those intentional journeys and accidental side trips, taking the form of a series of brief encounters with strangers. Depending on where you sit, the book is either an eccentric aggregate portrait of contemporary life in the UK or a mirror turned backward on an artist actively trying to renegotiate his relationship with photographic portraiture, or both.

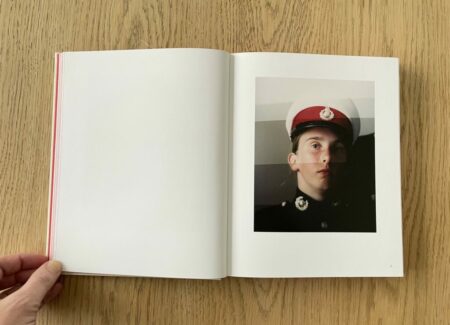

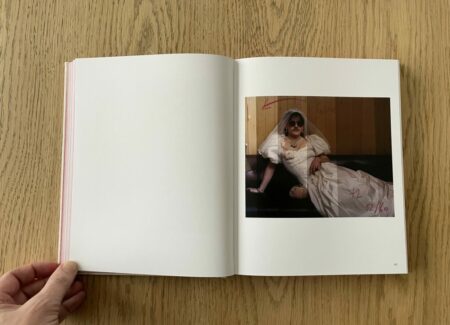

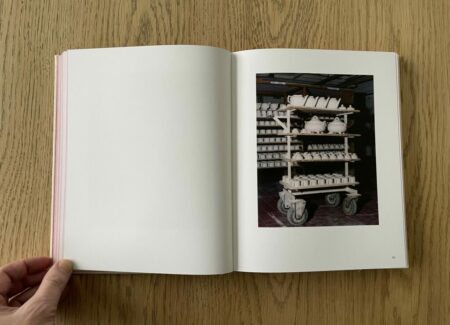

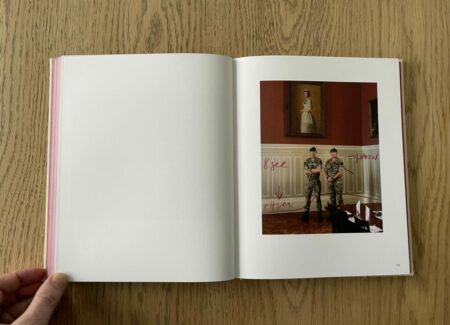

The stops along Chanarin’s itinerary turned out to be a diverse and seemingly improvisational grab bag – several homeless shelters, a local zoo, a West Indian carnival, some car and airplane engine factories, various art classes, an army barracks, a potato farm, a seaside location (in search of the Mayflower steps, which he didn’t find), and a gathering of Japanese rope bondage (and other fetish) enthusiasts, among various other locations and visits. The only link between these stopovers seems to have been Chanarin’s back-to-basics attitude of authentic openness to whatever he might find – each place or person had a story to tell (or be discovered), and Chanarin was seemingly a patient and quietly avid observer. An extended essay by the artist fills the back of A Perfect Sentence, offering an almost stream-of-consciousness recounting of his various encounters, intermingling the sometimes quirky events of the meetings and his searchingly thoughtful reactions to them.

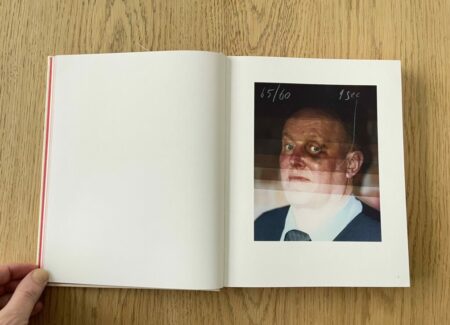

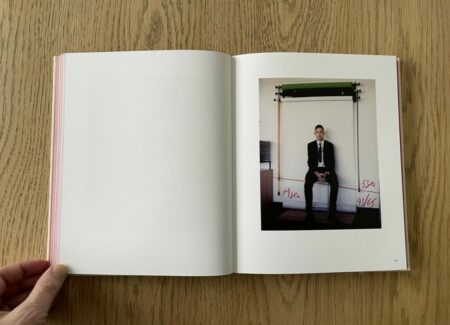

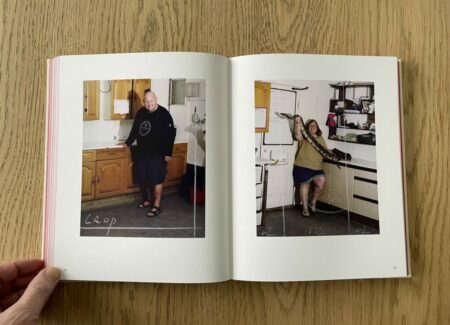

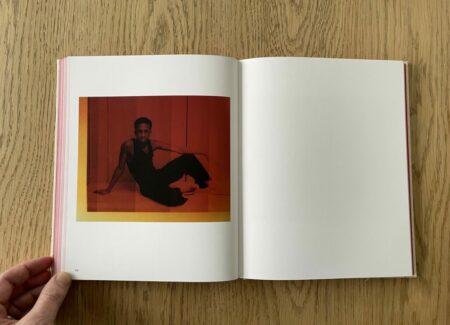

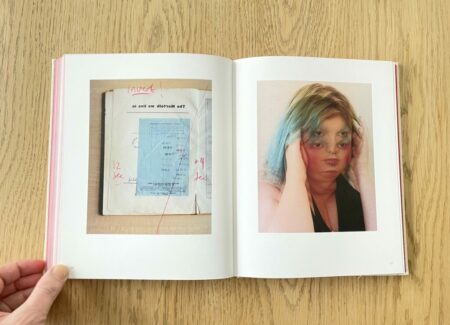

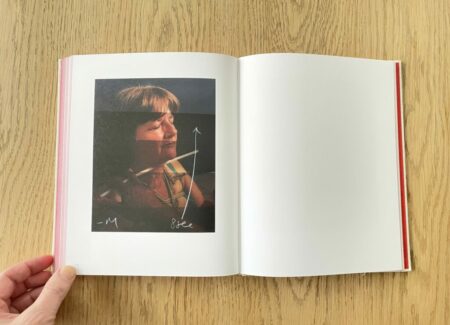

Starting with the very first image in the book, of an art class attendee with a black eye (which he apparently got during a rugby match but didn’t want to talk about), Chanarin’s aesthetic choices signal an overt discomfort with whatever he thought the old rules of documentary photography were. His photograph isn’t just a relatively straightforward head shot of Mark, but instead, the same image with various exposure strips and darkroom grease pencil markings included. These behind-the-scenes process details seem to call into question the “truth” of any one image that Chanarin might have produced, and offer a range of artistic variants, choices, and manipulations that the artist might have made. “Mark” could have been any number of these combinations, turning his single portrait into something more elusive and less definitive than we’re used to.

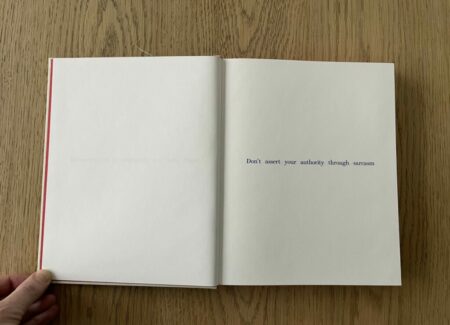

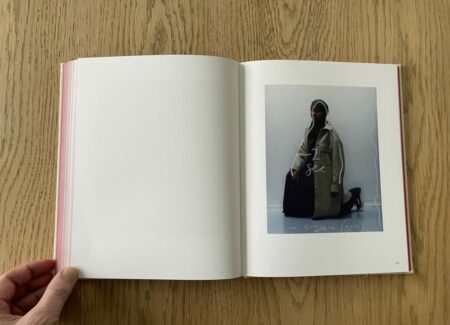

At least a third of the photographs in A Perfect Sentence offer this intentionally ambivalent view, seeming to acknowledge the complexities of the artist’s perception and perspective. A corner newsstand might be washed out or pop with vibrancy; a female cadet might look out from brightness or richer shadow; stairs to nowhere could be delivered in any number of color gradations; faces might be made lighter or darker in the darkroom, contrasts might be dampened or amplified, and multiple exposures might offer variant moments of the same scene piled atop one another. These images ask us to wrestle with these possibilities, forcing us to rethink our relationship with the photographs. Chanarin isn’t offering one truth but many, and perhaps the pictures reflect his front-of-mind uneasiness with the things he used to take for granted about image making.

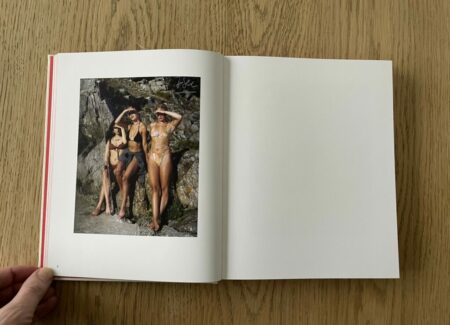

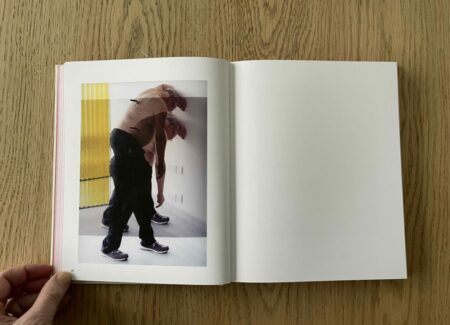

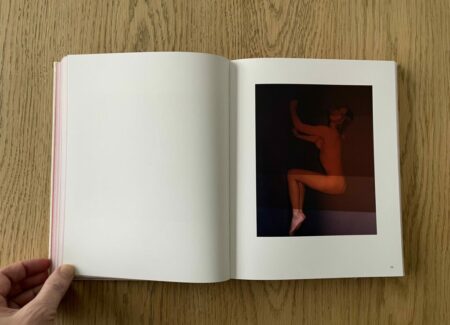

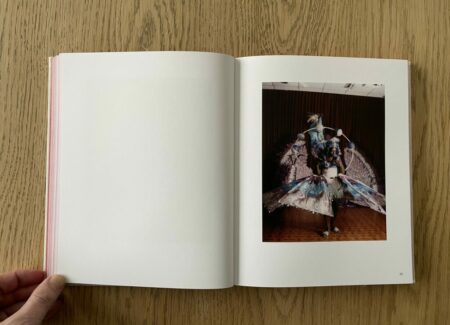

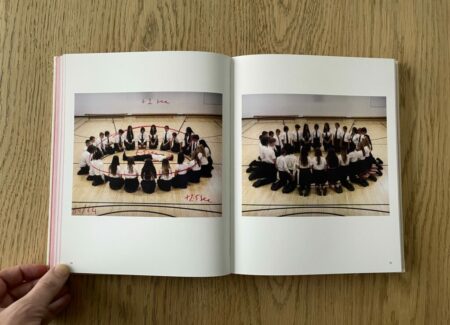

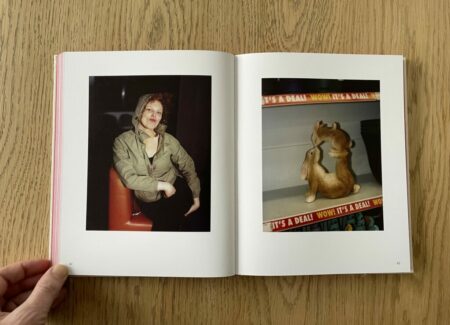

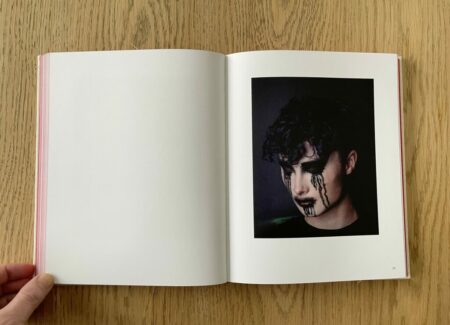

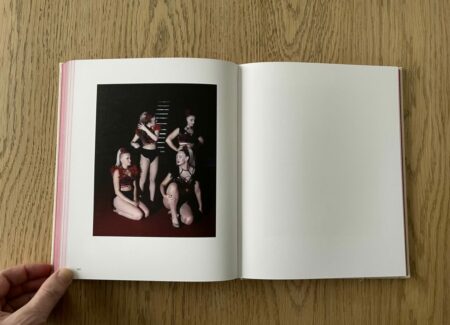

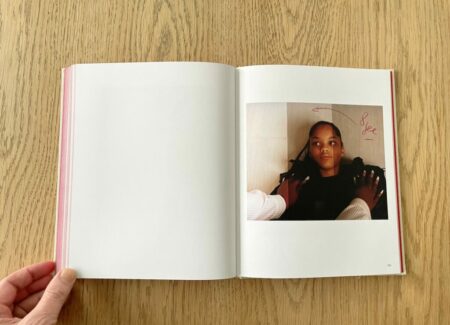

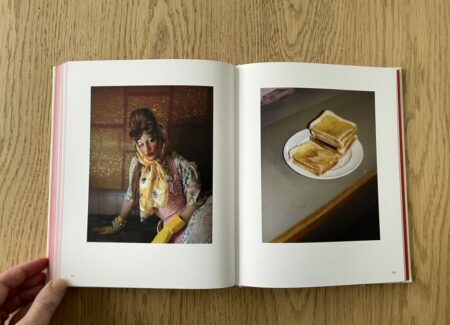

Many of the rest of Chanarin’s photographs, both portraits and still life discoveries, come at this uncertainty of vision from another angle, seemingly not selecting the “most perfect” or “most obvious” moments, but instead opting for images made before or after those kinds of scenes, where the framing is still being adjusted or the sitter isn’t quite settled. What this produces is a kind of slightly off kilter mood, where neither the photographer nor the subject has his or her best game face on. Three young women in swimsuits shade their eyes from the bright light and watch the photographer warily; a nude kneeling man picks at his teeth; a group of costumed dancers waits with hands on hips and fluffs their hair; West Indian parade participants pose awkwardly in some empty room and check their phones; a group of uniformed school kids perform some inexplicable circle ritual in a gym; and a nude woman poses on her hands and knees, with and then without socks.

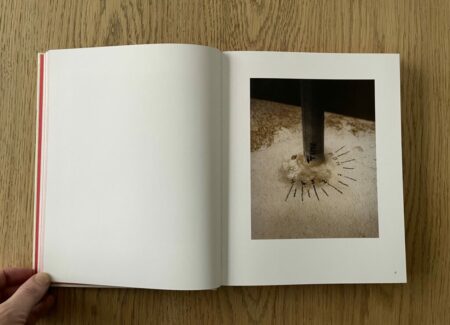

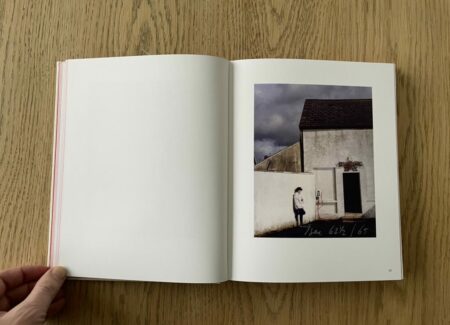

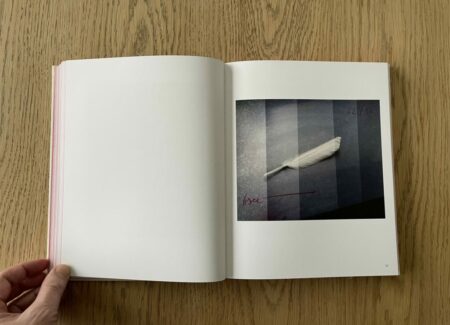

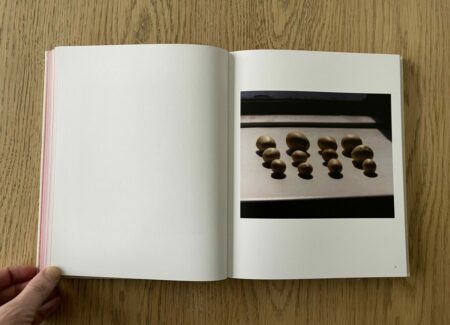

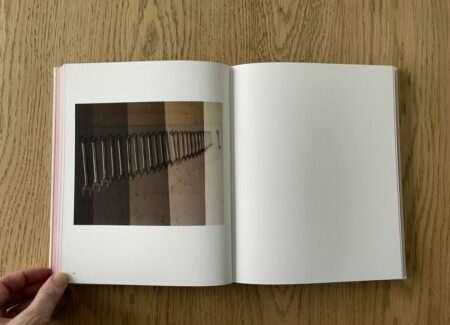

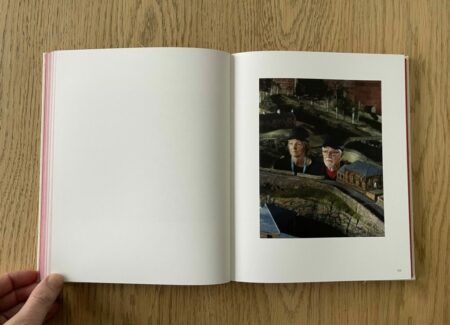

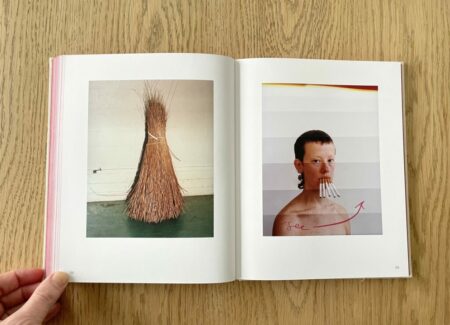

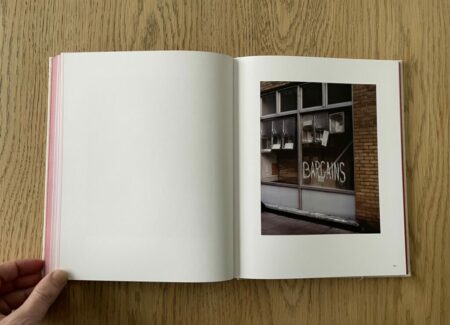

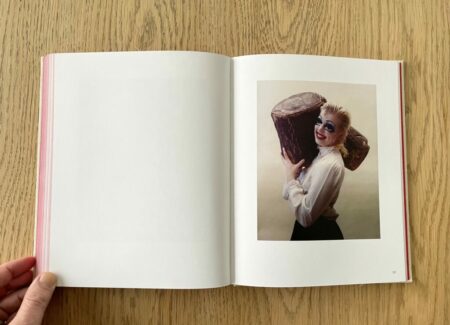

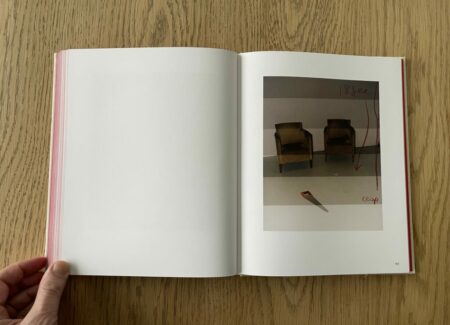

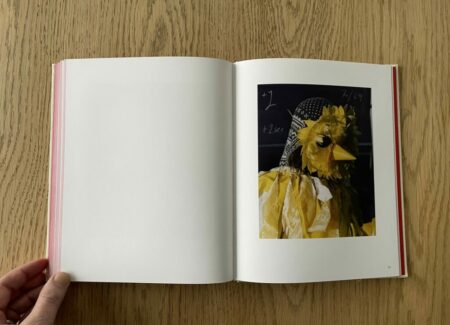

Still other images lean into photographic mistakes, or simply embrace a kind of found weirdness that defies easy explanation. The photographic misfires offer a sense of seeing and reseeing, where Chanarin examines his failures to capture what he wanted. The label on a ketchup bottle has been reversed, as has a book page of library stamps; the light on a building is washed out and overexposed, and resultingly marked “bad”; the edge of an inexplicable still life of two chairs and saw has an edge that needs to be cropped out; and the colors are wrong in various images, “too yellow” in one place, and needing to be yellow in another. In between, Chanarin offers us puzzling episodes with a protester wearing a chicken costume, a pile of buttered toast, a man with a fake stab wound in his back, a woman in clown makeup carrying a massive tree stump, a window display of “bargains” (in the form of aluminum sinks), a boy with half a dozen cigarettes in his mouth, a bundle of dry grasses, a bald man with a tarantula on his head, arrangements of potatoes and wrenches (by size), and two people poking their heads out from inside a model railroad display. Each page turn feels like a small adventure, with the overall flow coalescing into a feeling of consistently being unsure and unsteady, but reaching out to the world nonetheless.

A Perfect Sentence is certainly one of the most unorthodox photobooks of the year, but underneath its mystifying surface lies a genuinely thoughtful engagement with the medium. One of the last images in the photobook captures the lyrics on a karaoke machine “oh oh oh oh ooh, try everything”, which is then repeated. And while I can’t identify the song, as an intention, the words feel altogether appropriate to Chanarin’s state of mind. This is a book with conversations that don’t go as envisioned, encounters that didn’t exactly work out, and pictures that fail in one way or another, and yet, there are nuggets of ideas, insights, and learnings on almost every page, delivered with an openness (and lack of editorial protectiveness) that feels surprisingly novel. Gamely, Chanarin allows us to watch his thrashing and inward questioning, and there is an unassuming freshness to many of his photographic experiments that forces us to rethink some of our own assumptions about how the medium functions. I’m guessing that this is a photobook that many will not entirely appreciate, but it takes some risks (and creates some artistic chances) we haven’t seen before that are very much worth considering.

Collector’s POV: When Oliver Chanarin was working with Adam Broomberg, their joint gallery representation included Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg (here), but since their artistic split, their individual relationships seem more in flux. Chanarin’s individual work has little secondary market history, so interested collectors should likely connect directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar.)