JTF (just the facts): Co-published in 2024 by Aperture (here) and Jesus Blue (here). Hardcover with dust jacket, 12.9 x 9.84 inches, 72 pages, with 61 color photographs. Design by Laura Genninger. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: The British artist Nick Waplington was barely out of high school in 1984 when he first began hanging around the Broxtowe housing estate in Aspley, Nottingham. He’d been drawn to the site initially to visit his grandfather Walter. He soon developed relationships with nearby neighbors and family friends. An aspiring art student, he began to make photographs during his sojourns, focused in particular around the frenetic domesticity of two young households of Broxtowe. He made regular visits over the course of several years, generally on Saturdays. As later described by John Berger, this was the “day for having fun. Day for watching football…Day for letting parakeets out of their cages…Day when Nick comes around.” Strung together, those days gradually extended throughout the second half of the eighties, all without much fanfare.

When Waplington’s Broxtowe photos were finally published as Living Room in 1991, they touched an immediate nerve. The book had arrived fortuitously at the nexus of several cultural currents. From a sociological perspective, it could be considered a verdict on Thatcherism and its effect on the working class. Stylistically, it dovetailed with the late eighties ascendence of documentary color photography in the UK. Subjectwise, it exemplified photography’s shift away from globetrotting adventurism and toward more personal and intimate projects. If Nan Goldin’s view of family was from the back seat, and Sally Mann’s from the back deck, Waplington’s perspective was from a hamster ball dodging toddlers in tight quarters: chaotic, grubby, disoriented, and freewheeling.

Bound into a tight edit and then published with the imprimaturs of photo heavyweights John Berger and Richard Avedon, the young upstart’s debut monograph proved irresistible. Living Room made Waplington’s name, and it still remains his most celebrated work (he has since transitioned from photography to painting). But alas, the original Living Room is long out of print. For the current book collecting generation, copies are generally rare and inaccessible. Meanwhile, social inequality and memoirist expression remain salient issues, but photographically and in society at large. High time for a reprint.

Aperture to the rescue. In collaboration with Waplington’s personal imprint Jesus Blue, they’ve republished Living Room. Photobook purists will be happy to learn that the 2024 version follows the original design nearly to a T. The essays by Berger and Avedon have been stripped out. Apart from that change, the book’s size, materials, palette, typeface, layout, dedications, colophon, and cover blurbs are virtually identical to the 1991 edition. The similarity is close enough to fool most casual readers, and a fair number of seasoned experts.

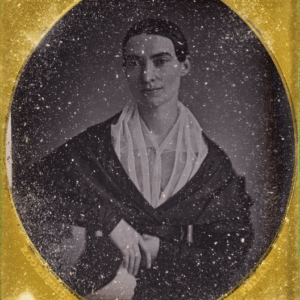

But hold on a moment. One book component has been altered in the new edition, and it is no minor detail. Every single photo is a surrogate. As explained in an enclosed flier, “this new work follows the same sequencing of landscape and portrait images as the original edition—replacing each of the 59 photographs with an as-yet-unseen work from the Living Room archive, often from the same roll of film as the original image.”

Say what? This head-spinning revision casts the book in a whole new light. What we had taken for a routine reprint is actually a bold experiment. But what exactly is being tested, and what is the motivation? Has Waplington grown tired of his old images? Is this a conceptual piece? An attempt at rebranding? A statement about the relatively importance—or unimportance—of editing? Or perhaps he just wants an excuse to revisit and share unseen work?

One can only guess at the precise motivations. But one thing is clear: The new Living Room remains a powerful body of work. In visual tone and voice, it is nearly as compelling and mystifying as the original. With his 6 x 9 camera and wide angle lens—and the occasional panoramic frame—Waplington leveraged in-your-face proximity and radically unpredictable vantage points to capture the energy, spunk, and mess of kid-filled spaces. Whether photographing a trip to the ice cream truck, an armful of squirming pets, or fleeting degrees of informal disrobing, his frames were direct and true. In Avedon’s words, they were “made from the center, inside out…All these cross-purposes create a hilarity of incident,”

Indeed some were hilarious. Some were tragicomic. All were frantic. The magic of the project is that any young parent could relate. Those parents—along with a general readership—will still be in familiar territory with the new edition. The cast of characters has expanded slightly, some new locations added, and some deleted. But Living Room’s essential warmth, humor, and humanity is intact.

For readers aesthetically biased toward stellar frames—which might include a majority of photographers?— the situation is more complicated. Among its 59 original images, Living Room included a handful of spectacular one-offs. Indeed, this is one aspect which lifted it above the contemporaneous photobook fray. Take Waplington’s photo of three performing kids and a ceiling lightbulb, for example, viewed from floor level. Or his panoramic of a late night party with its perfect horizontal swath of colors, roles, and expressions. A portrait of family members in a moment of reverie on the couch was penetrating and final, as was a gleeful dad stringing toddlers upside down like laundry. And what about the panoramic sweep from rabbit’s foot loafers through blurry torsos and magazine-strewn lazy boys, centered around an infant frozen in unforgettable milk vomit? These frames were killers. They laid the foundation for the entire book. Are they so easily replaced?

For some images at least, Waplington’s answer seems to be yes. There are perhaps a half-dozen new pictures here which are slightly different versions of the 1991 edit. Perhaps they were shot a split second before or after. In any case they’re from the same contact sheet. That’s certainly true of a new frame showing a man working under a car outdoors. It’s nearly identical to the original version, giving it a spot-the-difference quality in comparison. A new photo of a boy’s “Empty” belly split visually by a vacuum cleaner nozzle is almost the same as in 1991, separated only by expressions and stance. A two spread sequence in the original book, of parents playing grab-ass, is replaced not from the same situation, but with another sequence exhibiting the same whimsical spirit. These are among several direct substitutes. In a few situations pictures from the same contact sheet have been resequenced to other parts of the book. Waplington’s replacements are generally subtle and understated. They don’t seem to alter the book’s trajectory much, if at all. It’s enough to make one wonder, why go through the trouble?

One explanation: Perhaps Waplington is merely flexing? By sharing these outtakes now, Waplington hints at the depth and breadth of his archive. By all evidence, he was on a photo heater at the time, shooting and thinking constantly about Broxtowe. A mirrored selfie in the new book hints at his steady devotion. But before now, who knew the full extent of it?

That’s one take. A more tantalizing possibility is that the new edit questions the nature of documentary photography itself, and its traditional reliance on curatorial refinement. What does it mean to pick the “best” image from a situation? Perhaps Henri Cartier-Bresson’s precept was a fool’s errand? What if some photo-ops do not lend themselves to singular frames? Maybe sheets of negatives shouldn’t be mined for gems, but treasured as a holistic resource? In fact Waplington has already produced two other monographs from the same body of work, 1996’s Wedding and 2015’s Living Room / Work Prints. Each casts the Broxtowe families in a slightly different light, as does the current book. Which one is the definitive take? We may never know.

I can’t affirm or deny these shifting editorial paradigms, but they feel more applicable now than in 1991. Singular images seem to be in general retreat, while archival reassessment has the upper hand. As an artist who has transitioned to painting, Waplington might be only too happy to leave photography an indecisive knuckleball as parting gift. Photographic analysis flutters here and there. Good luck making any solid connections.

John Berger’s essay has been sadly excised from the new version. But perhaps the late critic should have the last word anyway: “And always there is that thing that he has seen, I think, unlike anybody else: Pleasure.” This is Berger describing the joy of Waplington. “These photos are not icons of poverty,” he writes, “but, rather, painted cupolas of play.” And then, this foreboding affirmation: “Here is what it means to live…here is what is reduced to dust when bombs are dropped on cities.” The book is called Living Room for a reason. Thirty-three years after its debut, there is life in the project yet.

Collector’s POV: Nick Waplington is represented by Hamilton’s Gallery in London (here), T.J. Boulting in London (here), and 1972 Agency in Brooklyn (here). Waplington’s work has little consistent secondary market history in the past decade, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.