JTF (just the facts): A total of 111 photographic works, in black-and-white and color, exhibited on the entire second floor of the museum. Divided into eight rooms, the presentation of the artist’s prints is roughly chronological, from 1967 to 1997. Most of the prints are vintage, although 23 are not. The photographs made by others date from the 19th century to 1992.

The photographic breakdown of the exhibition is as follows:

- 80 chromogenic prints

- 11 gelatin silver prints

- 6 offset lithographs

- 7 dye transfer prints

- 1 gelatin silver print with applied color

- 3 albumen silver print from glass negative

- 1 albumen print from paper negative

- 1 inkjet print

- 1 work of gelatin silver prints mixed with chromogenic prints and oil enamel

In addition to photographs, the exhibition also includes:

- 2 opaque watercolors on paper, 18th century India

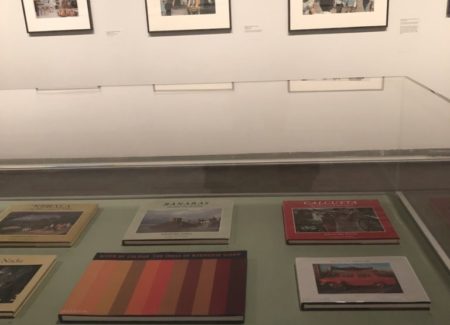

- 14 books

- 15 etchings

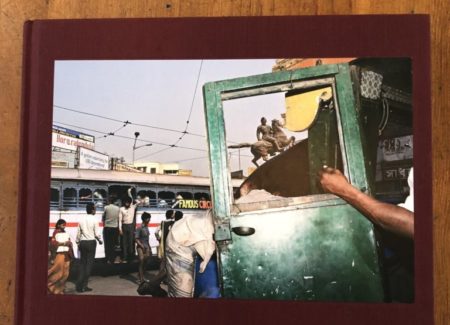

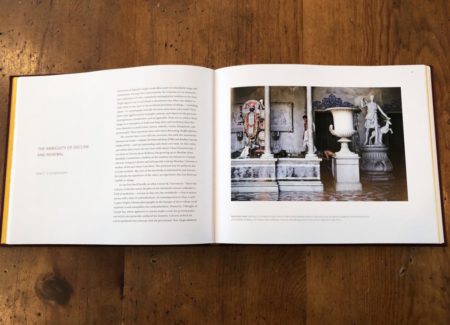

A companion catalog is published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (here, 176 pages, 134 color illustrations, 11 ½ x 9 ¼ inches.) Mia Fineman has written the main essay and edited contributions by Amit Chaudhuri, Shanay Jhaveri, and Partha Mitter. $50 hardcover. (Installation and catalog cover/spread shots below.)

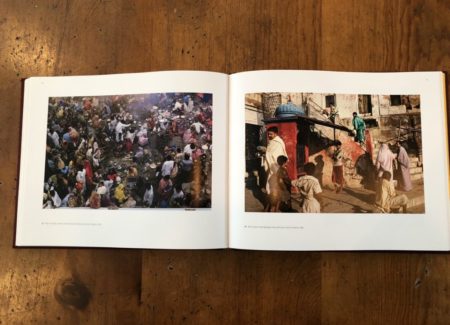

Comments/Context: To photograph a place in depth, with an eye for nuance and detail, and not vacationer cliches, one should be familiar with the history of its representation in words and images as well as the customs and daily routines of its people who live there. No one was more aware of these obstacles when confronted by the motley panorama of India—or prepared himself better to overcome them—than Raghubir Singh (1942-1999).

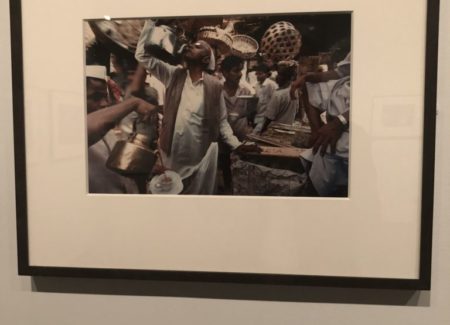

Absorbing the modernist aesthetics of European and American street photography, exemplified by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Lee Friedlander, Singh was more scholarly than either of them. As he learned to apply swatches of color to their dynamic compositions of life-on-the run, he also seemed to question if their quick-draw reactions to a scene were sometimes insufficient when photographing in strange places. As in the U.S., the religious and cultural diversity of India can be overwhelming to an outsider. The obvious seems everywhere in front of you, enticingly so. Singh minimized the challenge by being born there and by studying the writers, artists, and photographers who preceded him to a particular locale.

His 14 books and numerous magazine articles explored his native country from north to south. Self-taught as a historian as well as a photographer, he was versed in the Mughal miniaturists as well as the British colonial photographers John Murray, Samuel Bourne, and Linneaus Tripe. When he worked in a sacred place, such as the holy city of Benares or along the tumultuous Grand Trunk Road, he photographed with the words of Naipaul or Kipling in his head.

And yet he was perhaps more enchanted by the romance of India than by the petty aggravations of daily life there. After adulthood, when he was not offered a position running the family tea plantation, he preferred to visit for long periods, choosing instead to make his homes in Hong Kong, Paris, London, and New York. He remained split in his existence for practical reasons. After the 1970s, his modest income depended on freelance assignments from magazines and teaching photography in universities. India offered almost no opportunities at the time in either profession. He shot Kodachrome and the film could neither be bought nor processed there.

Even so, such legitimate concerns don’t tell the whole story of his conflicted relationship with his home country. The Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray, one of Singh’s cultural heroes, endured worse difficulties getting his films made locally and yet never became a nomad or émigré. Among the outstanding street photographers of the late 20th century, perhaps only Singh and Josef Koudelka were quite so transient.

Born into an aristocratic family in Rajasthan, Singh carried himself as one suited to commune with those of the same intellectual caste. He had high standards and was quick to dismiss those who in his mind didn’t meet them. His fiery temper burned many bridges. He had a long and contentious rivalry with Raghu Rai, more popular with segments of India’s art and photo community but without Singh’s reputation in the upper reaches of the U.S. and Europe art world.

Modernism on the Ganges builds upon the excellent 1998 retrospective, River of Color, which Singh lived long enough to help select. The Met’s curator Mia Fineman includes a number of images from the earlier show, such as Waiting Out the Floods, Banaras, 1983, but has added many just as vibrant that did not make that cut. Above all, she wants to set him within a wider context as an artist with a unique European-Indian sensibility.

I am not convinced by the suggestion, proposed by Singh and Max Kozloff, that Mughal miniatures informed his eye for color. Walking through the show, the formal and social elasticity of Cartier-Bresson feels like the dominant force shaping most of the imagery, sometimes eerily so. The multi-focused complexity of his compositions has more to do with the ungrounded perspective of the handheld camera and the de-centered optics of the wide-angle lens than with Indian painting or textiles. But I am open to persuasion and grateful for the essays in the catalog by Amit Chaudhuri, Shanay Jhaveri, and Partha Mitter that broaden the perspective we have known.

Singh first attracted the attention of editors in the U.S. and Europe for his 1967 photographs of riots in Jaipur. They would turn out to be anomalous in his oeuvre. During the ‘70s he rebelled against the strictures of photojournalism and his projects thereafter were never newsworthy. Social conflict is often not far below the surface in his images, but it’s rarely overt. The bedraggled men grotesquely swathed in black, red, and green powder, in a 1990 photograph, aren’t victims of an explosion; they’re revelers at the festival of Holi.

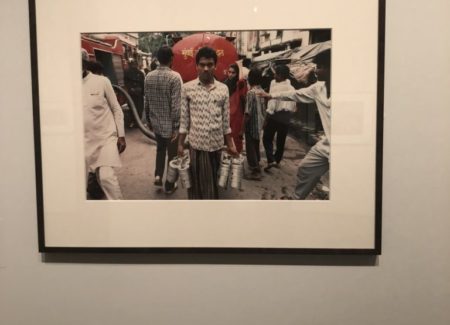

Is it a sign of Singh’s upper-caste attitude that the only people named in his portraits—Satyajit Ray, Dr. Mahir Mitra, the actress Aparna Sen, the poet Sakti Chattopadhyay—are artists or professionals? When he photographed individuals further down the ladder, they are usually anonymous and often defined by their function in India’s intricate and rigid hierarchy: A Porter in a Zaminar Mansion, Calcutta, Bengal, 1971; Dhabawallah, or Professional Lunch Distributor, Bombay, Maharashtra, 1992; Fruit seller and a Boy with child at Zaina Kadal Bridge , Jhelum River, Srinagar, Kashmir, 1979.

Or was Singh more like August Sander than we may have realized? He photographed India far more systematically than did Cartier-Bresson. What his friend Thomas Roma has done in Brooklyn, taking his camera around its many neighborhoods, Singh did on a sub-continental scale, going to more than a dozen states and publishing books on them, from Calcutta (1975) to Tamil Nadu (1997).

Fineman has integrated Singh’s photographs with ones by his friends and colleagues (Cartier-Bresson, Friedlander, William Gedney, Helen Levitt) as well as by precursors of either street photography (Atget) or Indian documentary (Bourne and Murray.) She has also included two examples of Indian painting from the 18th century.

This approach pays dividends in several instances. By placing a 1975 photograph by Singh of a village girl in Rajasthan riding a swing next to an 18th century watercolor of the same subject, Fineman isn’t suggesting the earlier one influenced the later but that deep waves of continuity roll beneath centuries of Indian culture and art. Friedlander’s fascination with reflections in glass, building pictures out of partial or fractured views, clearly had an impact on Singh.

Fineman’s East-meets-West idea might even have been improved with the presence of color street photographers other than Levitt (no Meyerowitz? no Eggleston?) It makes less sense, though, in the last section, which features a series of color etchings from 1996 by Anish Kapoor. As much as I appreciated knowing that Singh regarded Kapoor as “the greatest modern sculptor and painter that India has produced,” the inclusion, like that of a piece by John Baldessari, feels dictated by trends in museum politics: interdisciplinary shows are the ideal because they encourage the breakdown of insular departments. If Kapoor’s studies in abstract color had been hung closer to Singh’s photographs from the late ‘90s, which were moving in that direction, the ties between the two would be easier to assess and Kapoor’s etchings wouldn’t look so orphaned.

Singh’s last and greatest body of work, a series built around the Ambassador automobile, occupies a room at the back of the show. His affection for this stalwart and underpowered car, like the soft spot nurtured by East Germans’ for the Trabant, was shared by many Indians who saw the car as a symbol of independence. Manufactured locally, in West Bengal, from 1958-2014, the Ambassador also bore a colonial past in its parts and chassis. Hindustan Motors based its prototype on the British Morris Oxford series III. Its boxy shape and stodgily unchanging appearance earned it the epithet “bowler hat on wheels.” For decades, with the company safely protected from competition by Congress Party laws, the car was ubiquitous on the roads of India, as urban taxis and government vehicles. For millions of Indian citizens hoping to advance their status in society, the Ambassador was aspirational.

Two photographs from this series, the final ones in the catalog, are among the most daring and impressionistic that Singh ever made. In both, clouds reflect and refract in the car’s windows. In the first, taken in Karnataka (1994), the blue sky and piles of white cumulous stretch across the entire top half of the picture, landscape and machine dissolving into the empyrean of each other; in the second, from Gujarat (1997), the sun is low and hidden behind a skein of clouds. This piece of weather is further darkened by the purple, tinted sunscreen at the top of the windshield. Through the untinted central part, Singh’s camera looks toward a water tank (a pond and trees), and, on the horizon, what appears to be a shell of a house. The Ambassador’s hood protrudes like a snout at the bottom of the picture.

Recalling automobile photographs by Robert Frank, Dorothea Lange, Eggleston, Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand, Singh’s contributions to this long tradition were unique and, as they were imagined as part of a larger historical statement about technology, India, its people—about mobility, figuratively and literally—they are in my mind more profound than any of the others.

“The fundamental condition of the West is one of guilt, linked to death—from which black is inseparable,” Singh wrote in 1998. “The fundamental condition of India, however, is the cycle of rebirth, in which color is not just an essential element but also a deep inner source, reaching into the subcontinent’s long and rich past.”

The sense that life and death are inseparable is a distinct feature of India. The feeling is in the ground and air wherever you step or breathe in India, and it’s everywhere in Singh’s photographs. It’s why the crowd and the family, not so much the individual, animate his eye, whether in villages or cities.

Singh died as the digital economy was transforming India into a colossus of the information age. His images register the patience, suffering, ingenuity, perseverance, and beauty of more than a billion souls going about the gritty business of survival as a proud and independent people. No photographer pictured as clearly the inevitable clash of capitalism as it slowly eroded–and adapted to–millenniums of crushing religious and social norms.

My only complaint with this show is that Singh made many more superb photographs than the 80 hung here. Seek out his later books. You won’t be disappointed.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are of course no posted prices. Raghubir Singh is represented by Sepia Eye in New York (here), and a show of his work from Bombay is currently on view at Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York (here). Singh’s work has only an intermittent history at auction in the past decade, with too few lots coming up for sale to generate a consistent price pattern. As such, gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.