JTF (just the facts): A total of 47 photographs exhibited on five gray-painted walls in the western room, on three walls in the small northeastern room, on two walls in the office, along the corridor, and in the easternmost room. Fifteen of the prints are gelatin silver vintage; the rest are contemporary archival pigment prints, of which 4 are in color. The 24 x 36 inch archival prints are in editions of 7+2AP; the 40 x 60 inch archival prints are in editions of 5+2AP; the vintage gelatin silver prints are either 11 x 14 or 16 x 20 inches (or the reverse). All the works are dated between 1972 and 1998. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: I first read the name Ming Smith more than 40 years ago when studying the credits on album covers by the jazz saxophonist and composer David Murray, to whom she was then married. Of the twelve LPs I still have by him, records dating from 1979-1985—so glad I never threw away my vinyl!—her photographs appear on ten of them, usually on the cover.

A name like hers is hard to forget—what conjunction could be more American?—and her images, especially the ones of figures and places dissolved into blurry patches of color, were artful counterparts to Murray’s skeins of sound. He is a ferocious and nimble free-jazz player who knows that the listener sometimes needs to be soothed by melodic lines and chord resolutions, one reason he is a peerless balladeer. She is a photographer who also wants us to perceive the forms behind what she’s representing, even if sometimes only dimly and within a whirlwind of energies.

Record covers were about the only place Smith’s work could be seen regularly in those years. She didn’t have representation in a gallery that I was aware of, although she belonged to the communal Kamoinge Workshop (the only woman) and was among the eleven members exhibited at ICP in 1975 (a show I didn’t see.) That year she also became the first Black woman photographer to have her work purchased by the Museum of Modern Art. This was not enough to sustain a career in the 1980s and ‘90s, fallow times for documentary, particularly for women of color.

Her fortunes have markedly improved over the last ten years. MoMA included her in its Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography in 2010 and the Steven Kasher Gallery gave her an 18-picture retrospective (only black-and-white) in 2017. About a dozen of her prints were featured in the traveling exhibition on Kamoinge organized last year by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond (reviewed here), and this year Aperture produced a monograph (reviewed here).

Her new show is her largest yet in a New York gallery. The title may have a double meaning: these photographs are the residue of what she has seen and how she has translated experience over some 35 years. “Evidence” is also the title of a Thelonious Monk composition, one of his simplest and trickiest, potholed with unexpected accents. First recorded in 1948, it was also known as “Justice” or “We Named It Justice.”

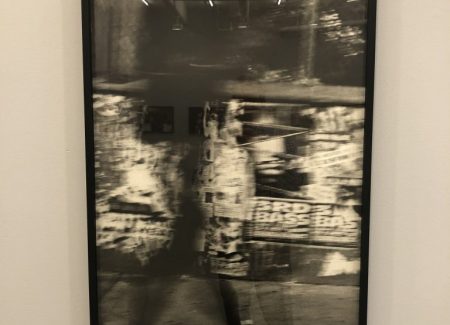

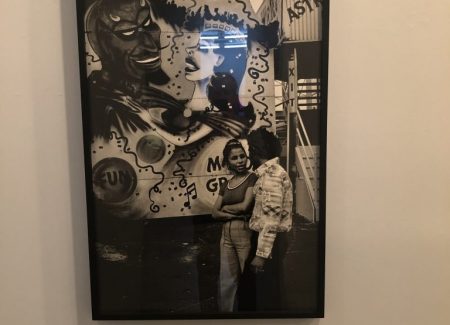

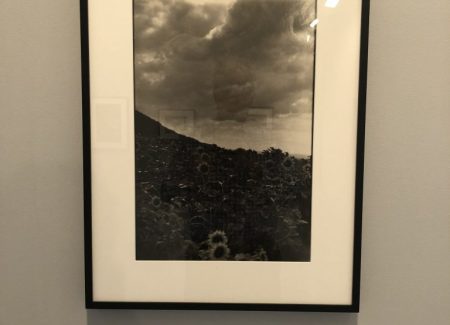

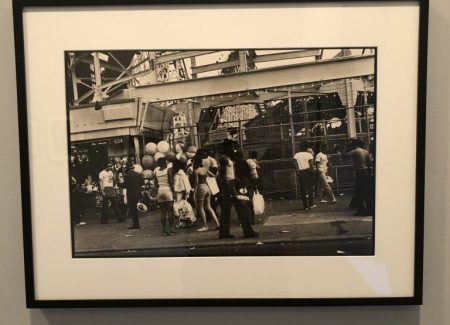

Smith’s work isn’t easy to categorize. Not a lot of her photographs are sharply descriptive. Her black-and-white and color palettes are dark and smoky. Shadows dominate, not in a threatening manner but as if for her they deserved equal weight to solid things and constituted a hidden reality of their own.

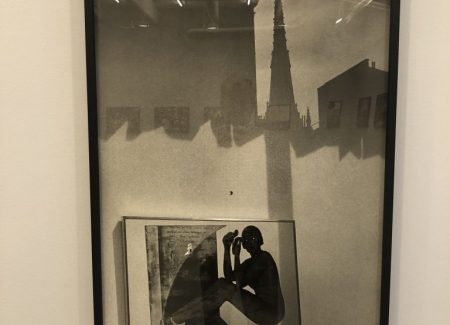

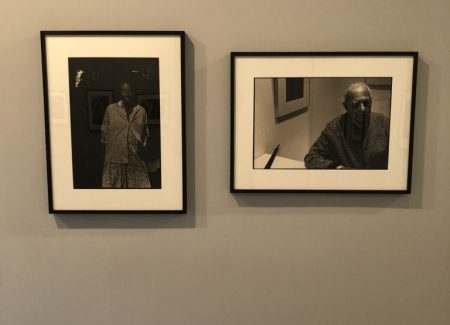

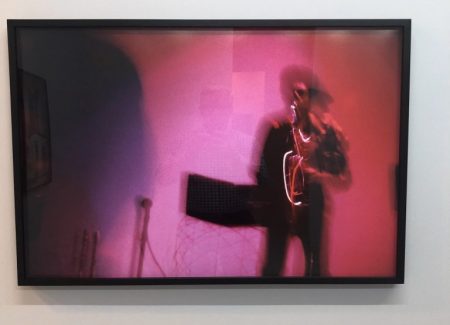

Most of the images here date from the 1970s and don’t adhere to a single subject or style. Her interests are wide and unpredictable: a close-up of a magisterial Grace Jones at Studio 54; cornfields in Columbus, Ohio (her hometown); a religious sculpture of Jesus and Mary in a Pittsburgh church (for a series on playwright August Wilson’s neighborhood); two middle-aged sisters wearing fancy hats and carrying fans on a Harlem street corner; a solo saxophonist rendered in frenzied red and pink; a distant flock of pigeons against a white sky in Trafalgar Square; a portrait of Brassaï; and a studio self-portrait in which she assumes the guise of Josephine Baker, complete with ball gown and a prop cheetah.

Smith was a successful fashion model in the 1970s and ‘80s and assignments took her to Europe, Asia, and Africa. Some of these photographs are among her least successful efforts and probably deserved to be edited out of the show: the Eiffel Tower with a Maillol sculpture in the foreground; flamingoes in a West Berlin zoo; and a man in silhouette looking at the ocean from a doorway in a Senegalese fort where slaves were shipped across the Atlantic.

Black music and musicians provide one of the through lines for the show. On the partition that faces visitors when walking into the gallery are four large black-and-white archival prints: two nudes cloaked in shadow (one male, one female) and two portraits of Sun Ra on stage at a club in NYC, the shimmer of his sequin robe and metallic headdress enhanced by a slow exposure.

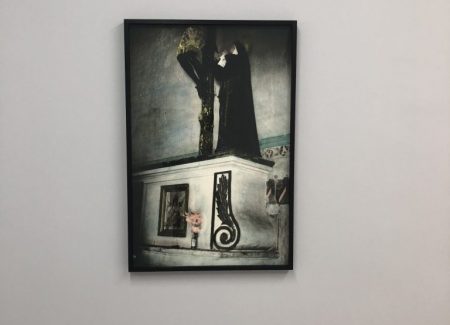

Blur for Smith is more about capturing the fluttery pulse of people and places than wrapping them in impressionist gauze. Acid Rain (“Mercy Mercy Me,” Marvin Gaye) is a street corner scene ca. 1977 showing four faceless young men in a smeary light, their heads silhouetted against a violet sky, a “Don’t Walk” traffic signal blinking behind them. (It was the cover of the David Murray Big Band Live at Sweet Basil, Volume 2 in 1988.) The Mexican church sculpture in My Father’s Tears (San Miguel de Allende) from 1977 show Mary Magdalene dressed as a Dominican nun and praying at the foot of the cross. It was the cover of Murray’s New Life, also released in 1988, the same year that his album Ming’s Samba appeared.

Even when documenting the ongoing movement for Black social justice, she doesn’t so much report on events as look for telling moments or gestures. In a pair of photographs from the 1998 Million Youth March in Harlem, she contrasts the raised hands of the speakers with the raised fists of the listeners in the crowd.

Smith’s photographs have been reproduced often enough by now that a few have become iconic. One of them is Dakar Roadside with Figures (1972), a sidelong glance à la Cartier-Bresson or DeCarava at a woman in a billowing shawl knotted to her dress, walking on a flat sandy sidewalk toward a tree bent like a bow. It could be called uncharacteristic of Smith if her oeuvre did not present so many angles that it’s hard to say what her photographic character is at its core.

A few words of praise and good wishes for the Nicola Vassell Gallery. The first Black-owned art space in Chelsea, it is making its debut with this show. Photography by Black men and women has been more plentiful in New York in the last few years than at any time in my life. With plenty of room and press materials that are a model of easy-to use information, this should be a place where artists who felt they had no place in the art world before will have a professional home.

Collector’s POV: Most of the archival pigment prints are priced at $30000, while the vintage gelatin silver range between $70000 and $90000, depending on size and rarity. Smith’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.