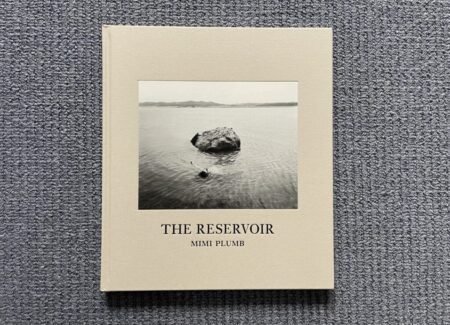

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2025 by Nazraeli Press (here). Hardcover, 11.5 x 13 inches, 68 pages, with 41 duotone plates. There are no essays included. In an edition of 1500 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

A special edition of The Reservoir is also available, with a slipcase, in an edition of 100 copies (here).

Comments/Context: One of the very real challenges facing photographers trying to highlight the wide ranging effects of climate change in the contemporary world is that so many of the changes taking place are slow and incremental. Photography is of course quite good at capturing discrete instants of time, but using it to document long term transformation is quite a bit harder – wildfires, hurricanes, floods, and other dramatic or destructive storms provide clear before and after scenarios to photograph, but other important shifts and alterations (like ocean temperature rise or species extinction) aren’t nearly as inherently photogenic.

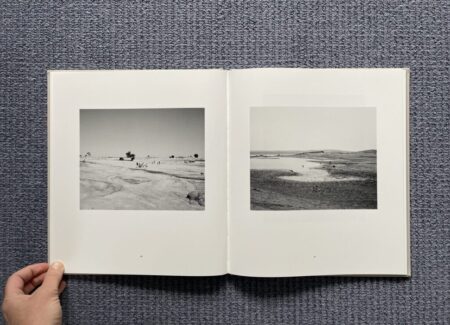

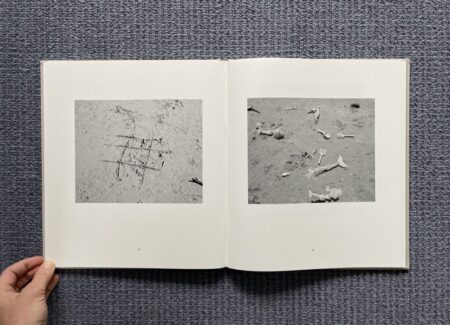

Drought is one of the tricker climate evolutions to photograph, if only because it is by definition an absence. A lack of water, or the slow drying up of available water sources, tends to be visualized by what has been left behind when the water goes – dry lake beds, docks and resorts that no longer reach the water, parched land, animal bones, and dead agricultural crops. Lower water tables, over pumped aquifers, and dry wells are even harder to visualize, aside from witnessing the trucking in of replacement water or the carrying of water in buckets or jugs across longer and longer distances.

The long term drought taking place in California’s Central Valley has now reached well into its second decade, putting increasing pressure on one of the richest and most developed agricultural regions in the United States. Typically fed by ample runoff from winter snowfalls in the nearby mountains, with annual snowpack levels falling year after year, the reservoirs designed to catch the flow are less full than normal, and drying out faster each year as temperatures rise and farmers (and nearby cities) pull out more and more water.

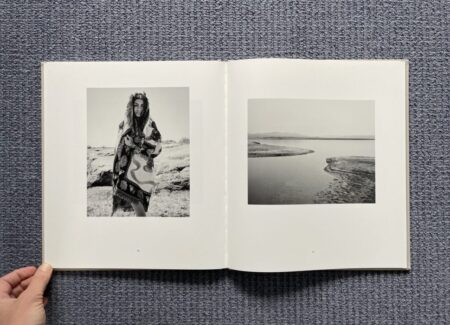

The Reservoir, as its straightforwardly descriptive title implies, offers a photographic survey of two reservoirs in the Central Valley, made by Mimi Plumb between 2021 and 2023 and supported by a 2022 Guggenheim Fellowship. A California native, who got her artistic training at the San Francisco Art Institute, Plumb has been riding a rising wave of attention for the better part of the past decade, starting with the rediscovery of her 1980s work via her 2018 photobook Landfall. This was followed in quick succession by a string of book projects, essentially rebuilding her back catalog: The White Sky in 2020 (featuring her earlier mid 1970s work, reviewed here), The Golden City in 2022 (images of San Francisco, largely from the early 1990s, reviewed here), Megalith-Still in 2023 (documenting a herd of horses, from the late 1990s through to the early 2000s), and Lookout on Highway 74 in 2025 (a smaller 1980s project.) The Reservoir is a new body of work, bringing us up to speed with Plumb’s current photographic interests and approach. It mixes arid black-and-white landscape images of the two reservoirs (and their receding lakebeds) with scenes of beachgoers and other visitors trying to avoid the heat, creating an intermingled and somewhat indirect portrait of the drought gripping the region.

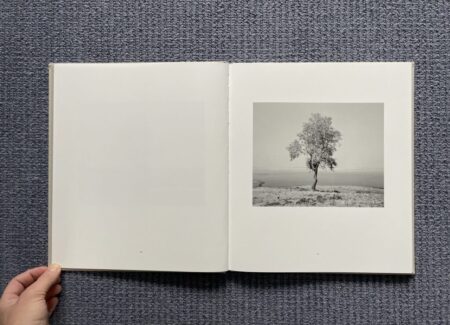

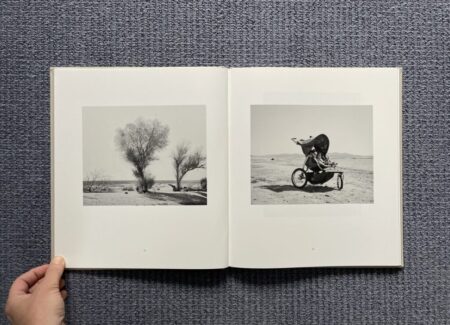

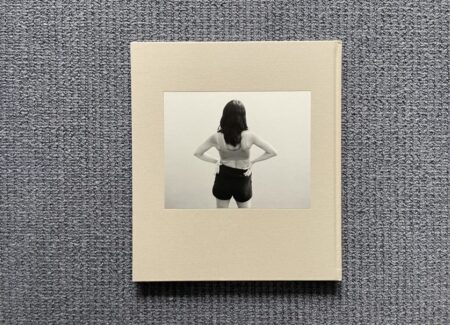

Plumb begins her photographic survey by trying to visually measure the drought situation, using three images of a lone tree as a yardstick. The first image (all of the photographs are undated) finds the tree submerged in the reservoir, the water rising several feet on its trunk and covering all of the nearby land. A few page flips forward finds the same tree, now just at the water’s edge, with the white froth of the waves at its base. The last image in the series is the most sobering, in that the same tree is now surrounded by rocks and grass with tiny figures walking on the sand in the far off distance – the water has receded a very long way, perhaps as much as a mile. The next page turn offers us a young woman standing with her hands on her hips looking out over a wash of indistinct grey, which after the step-wise series of trees feels like a gesture of frustrated judgement or resignation, the reality of the drought now altogether obvious.

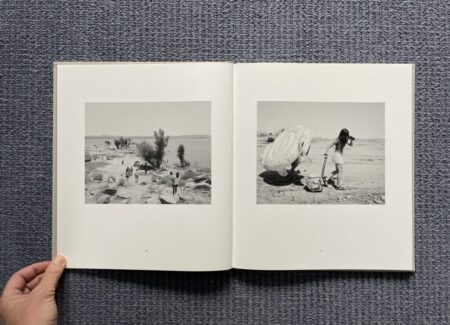

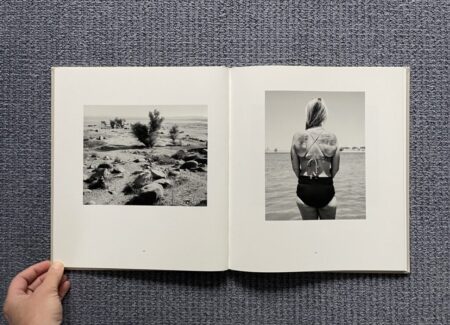

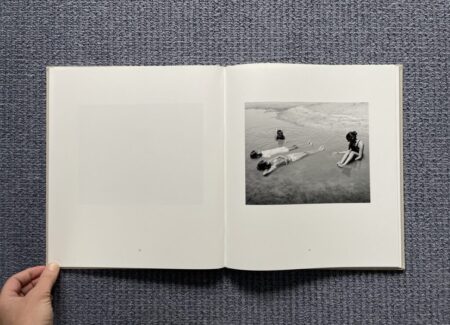

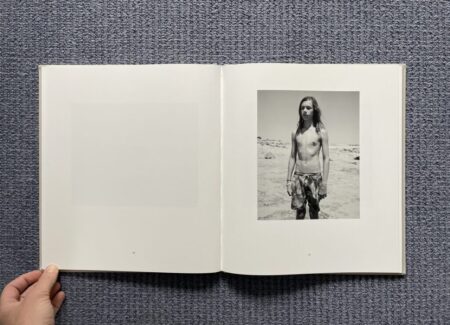

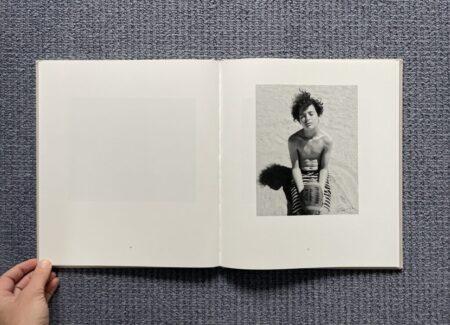

Many of Plumb’s images capture groups and families at the beach, in everyday scenes that feel familiar, like people wading and floating in the not-very-deep water, standing around in swimsuits, or talking and sunning themselves. Towels and backpacks are spread out in clusters, and bored kids play tic-tac-toe on the sand, bury themselves on the beach, or expectantly hold a football waiting for a game to come together. But the California sun is persistent and unrelenting, blasting each scene with blistering squint-inducing glare, leading the visitors to hide in the shade underneath the scraggly trees or to construct various improvised sun shields from towels, blankets, and tents.

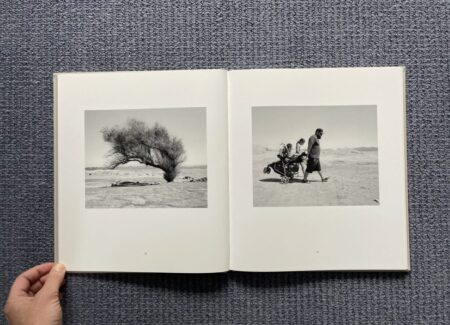

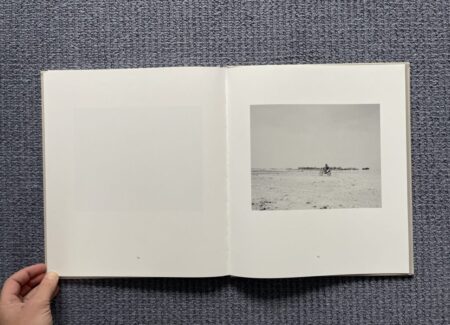

Once we start to notice these small adaptations, more and more ominous signs start to appear in Plumb’s pictures. Families trudge across wide expanses of sand and scrub, carrying floaties, tubes, and coolers, and dragging strollers full of toddlers, but they’re having to go further and further as the drought deepens. A few of these images have an almost dystopian flair, with intrepid families crossing stark open deserts and parched lakebeds on foot, with no shade in sight; others recall poses and scenes from the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, with desperate families on something like a pilgrimage to find water. Some of Plumb’s strongest landscapes use scale to memorable effect, with tiny figures set against vast flat emptiness or set down near the water’s edge with a gathering of rocks and something like a puddle of water nearby. Even the once sprawling areas where houseboats and pleasure craft dotted the lakes have been precipitously shrunk down, the boats now clustered together in what resembles a parking lot. The toy mermaids scattered and abandoned on the dirt are perhaps the most poignant of Plumb’s visual metaphors, their hair blown dry and their tail fins anxiously flapping.

If we were somehow to miss the broader message the Plumb is communicating in The Reservoir, the photographs that bookend the sequence make the point clear. The first image in the photobook is a full frame image of water, with a few sticks and rocks visible underneath and the sun glinting off the surface; its pair at the end is either literally or conceptually the same place, but it is now entirely dry, the sand parched to a hard crust. The duo offers another photograph time shift, a then and now comparison that feels altogether bleak.

This isn’t to say that Plumb’s photographs in The Reservoir are somehow less than beautiful. They are consistently richly tactile, with nuanced attention paid to tonal contrasts and resonant details. But that said, The Reservoir certainly packs a climate change punch, its observations aggregating into a mood of quiet despair, even on a sunny beachfront afternoon. Let’s hope Plumb’s image of a person on a motorcycle crossing the dry lakebed isn’t the new reality – if the distance to the water is becoming too far to walk, we’re collectively in trouble.

Collector’s POV: Mimi Plumb is represented by Robert Koch Gallery in San Francisco (here) and Galerie Wouter van Leeuwen in Amsterdam (here). Her work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.