JTF (just the facts): Published in 2018 by Stanley/Barker (here). Hardcover, 100 pages (unpaginated), with 59 black and white and color photographs. The images were taken between 1976 and 1988. There are no texts or essays included. In an edition of 1000 copies. Designed by The Entente. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: At first glance, Michael Northrup’s new photobook seems to be equal parts time capsule and family album, a self-contained journey back to the pictures he made in the mid 1970s when he first met his soon-to-be wife, and following along for the next dozen years through their marriage, the birth of their first child, and ultimately their divorce. It contains snapshots of sunny days at the beach, birthdays and holidays, moments of intimacy, and a consistent dose of quirky silliness and witty posing that alludes to shared good times, and then as the baby comes, evolves to include a few more moments of the blunt realities of motherhood and an obvious wearying toward the playful collaborative picture making that was once so much fun.

But as we look a bit closer, it quickly becomes apparent that nearly every image in the photobook contains Northrup’s wife Pam, and aside from a very few other people and their daughter (in the last few images), it is an entirely one sided visual story. We only ever see Northrup himself as a shadow, his dark presence cast across the pictures (or caught in a mirror) but never actually seen directly. So what might seem like a book about the complex ups and downs of a youthful relationship isn’t exactly that; instead, it is Northrup’s largely one-sided view, intermingled with the deliberate artistic effort to make (and in many cases, actively construct) intriguingly composed photographs using his wife as a model.

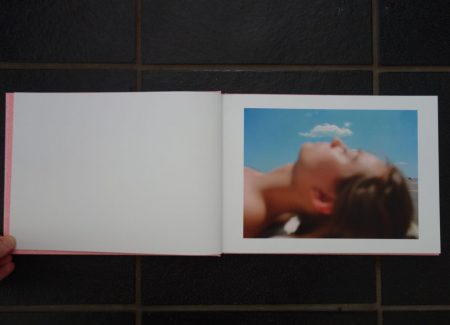

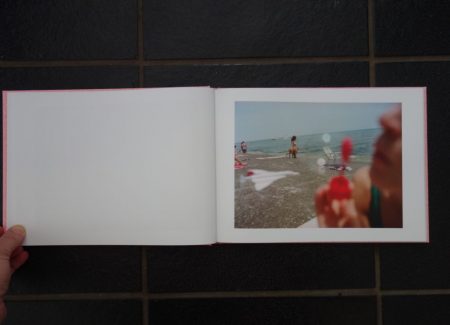

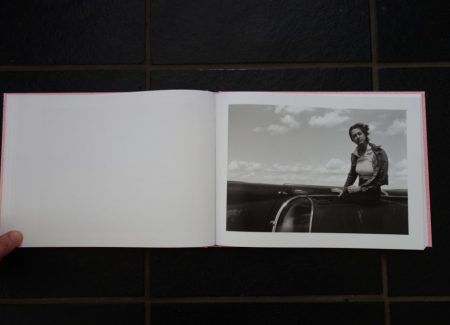

While there are likely a few true on-the-fly snapshots mixed in with the images gathered here, for the most part, the pictures bear the subtle hallmarks of careful planning and consideration, executed inside the bright-flash casualness of a “snapshot aesthetic”. The first and last images in the book, along with a few more in the middle, find Pam lying up close, so close that the focus washes her head in blur and centers on the action in the far background. As a group, they are an apt metaphor and bookend for this larger body of work, as we are constantly seeing the world through Pam, and compositionally, they foreground the relationship ahead of the beach or the grassy yard or anything else. While we might assume she wasn’t really paying attention to her husband as he was snapping away, one image of her blowing bubbles in the midst of this layered blur scheme implies that she was, at least at some times, a willing participant in Northrup’s image making.

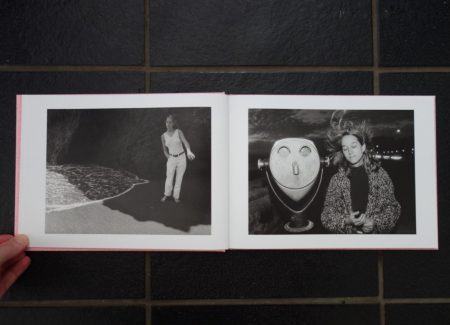

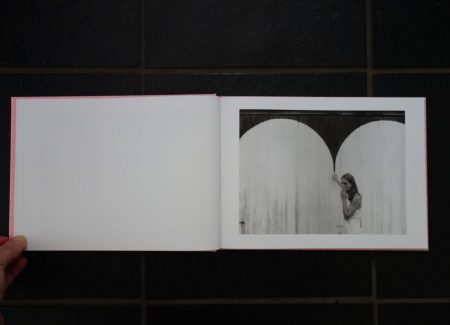

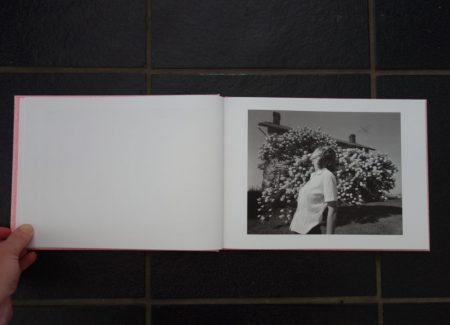

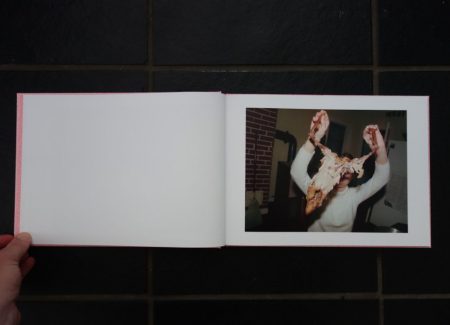

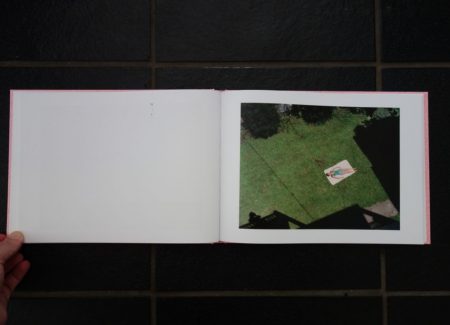

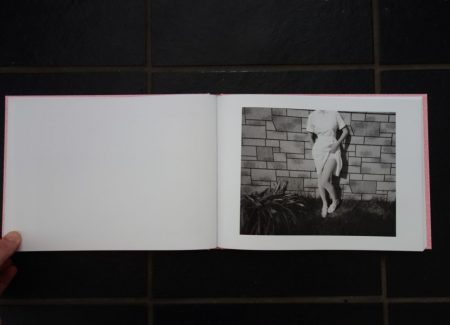

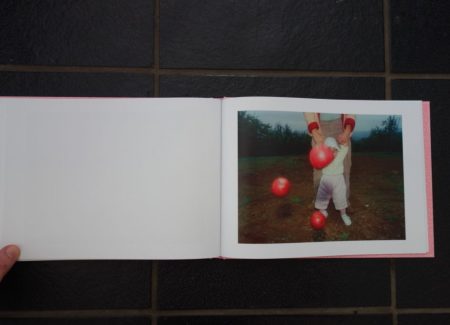

Other strategies also seem to confirm that the two were working together to craft many of these pictures. Items thrown into the middle of a frame are another favorite visual experiment, from plastic toy babies and glittery flowers interrupting Pam listening the baby’s heartbeat through a stethoscope to bright red apples tumbling mid-flight through a fall season mother-daughter portrait. And there are many images which simply show us a pose held for effect, a scene set up for its understated weirdness, or a typically private moment allowed by Pam to be photographed. She blows wispy billows of smoke, lets her hair blow in the wind, dramatically smells the flowers in bloom, and combs her eyebrows with a hairbrush. In other subtly surreal pictures, she holds up the stripped remains of a turkey carcass, offers up a homemade birthday cake with an overabundance of candles, rests her disembodied head on the clothesline, and lies like a corpse in a field of long grass. And she takes part in a bit of provocative image play in pictures of watermelon eating with her legs in the air, a bit of thigh shown from underneath a seductively raised nurse’s outfit, and various nudes peeking out from terry cloth robes. Seen together, the photographs have an undercurrent of frisky, prankish tenderness that feels wholly authentic.

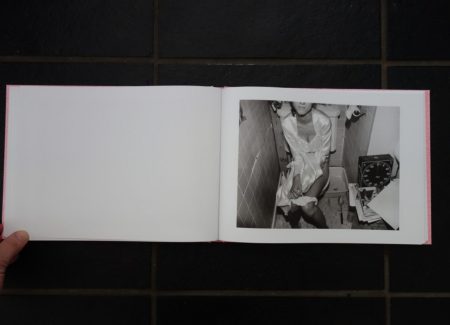

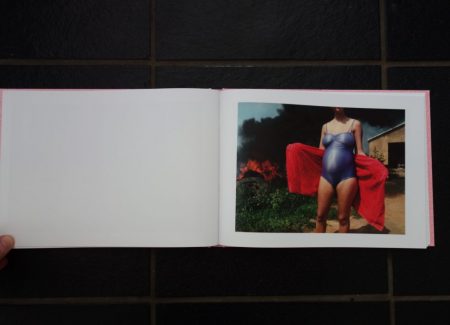

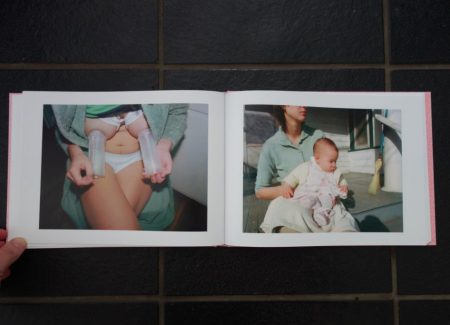

While there are several images of Pam in the first half of the book that catch her in an expression of mild displeasure, arms-crossed reluctance, or quiet reserve, it’s hard, at least at the beginning, to see these as anything more that being pushed just one too many times for just one picture too many. The fact that Pam allowed (or even encouraged) her husband to make pictures while she was peeing (in a shiny dress, near the cat litter box) and while she was pregnant (her swim-suited body posed near a smoky tire fire or her bulging belly poking out of her robe) seems to indicate that she was still willing to play along, even as she was getting ready to give birth.

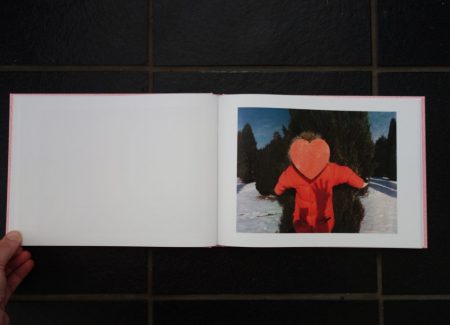

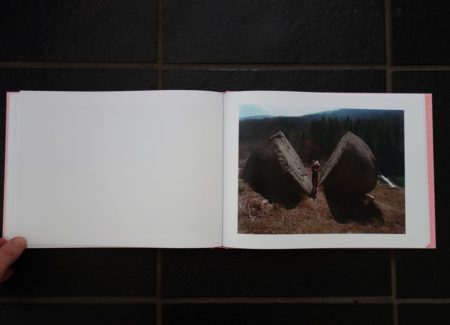

But once the baby comes, Pam’s demeanor noticeably shifts. She’s still taking part in her husband’s picture making antics, but the spark of impish mischief is pretty much gone. She stands with the baby in front of a snowy field of boxwoods at the mall, the bushy green spots in a perfectly oddball pattern behind her, but she’s distracted. She’s seen breast pumping, and bathing the squirrely child, basically caring for her daughter nonstop as most mothers do, the physical and emotional exhaustion written clearly on her face. She gamely holds the baby between a huge cleaved rock, rests on a blanket near a Halloween skeleton, pulls her daughter in a red wagon, and dances in the yard, but all of this seems to take an extra dose of effort.

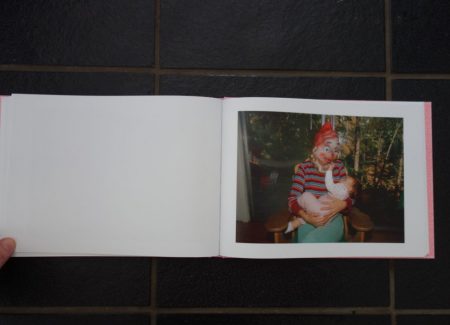

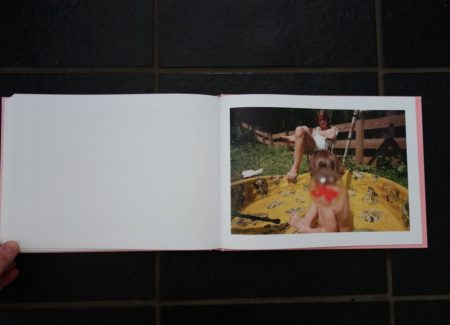

Perhaps as a physical sign of being overwhelmed or postpartum depressed, she cuts her once long hair, making her appearance more austere and giving her a passing resemblance to Diane Arbus. Several of the last few pictures in the book seem to allude to the alienation she might have been feeling. She wears a rubber mask while playing with the child, sits with her feet up on the kiddie pool, and in once case, looks back at the camera with an expression that seems to say she’s reached her limit with the whole photography project. The final image brings her back to the controlled foreground blur of the beginning, almost as if to say that we never really knew her at all.

Watching Pam’s trajectory, I certainly had the sense of real shared intimacy between she and her artist husband, and being invited inside that circle of closeness via these photographs is undeniably engaging. But as the book wore on and especially after the arrival of the baby, I felt like I could see the trouble brewing right on her face, so the fact that they parted ways at the end doesn’t come as a huge surprise.

Normally, our discussion of a solid book like this one would end here, but in this case, there is an additional twist. As was first discussed on Blake Andrews’ blog in 2013 (here), when Northrup made the first dummy of this photobook, he went back and asked Pam if he could publish these photographs made during their time together, and she refused. And yet, here we have this photobook in our hands to see and discuss (apparently as a different edit of the same body of work), so perhaps the circumstances changed or Northrup went ahead anyway, potentially against her wishes.

While the current situation isn’t entirely clear, the broader idea of publishing these pictures in direct contravention of the desires of an intimate collaborator in the project, if that is indeed what has happened here, certainly raises some bright line ethical issues (regardless of the legal technicalities of model releases and such). The unconfirmed idea that Pam didn’t want these photographs to come out now (whatever her reasons) meaningfully recasts the pictures for me, to the point that they feel like a potential invasion of her privacy. Whatever spell they first cast, particularly the magic of a young couple expressively collaborating to make art, is meaningfully diluted, leaving me feeling like seeing these pictures now is a breach of the trust that originally enabled them.

As a result, Dream Away leaves me wrestling with the time-based issues of consent in collaborative photography. While Pam’s consent was certainly freely provided when these pictures were being made – she could have absolutely said no at the time to the peeing picture, or the breast pumping picture, or the nudes, or anything else for that matter that she didn’t want to do or have photographed – that same consent was later apparently revoked. And even though that retroactively changes the rules of the original artistic partnership, which is clearly a problem, I’m hard pressed not to sympathize with her position, regardless of her reasons – even though time passes, I don’t think subjects forfeit their right to consent. The full arguments on both sides of this issue are beyond the scope of this review, but that doesn’t mean they don’t cloud the air that surrounds these otherwise engaging pictures.

Collector’s POV: Michael Northrup does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As such, those collectors interested in following up should likely do so via the artist’s website (linked in the sidebar).

This book was published without consent of Northrup’s ex spouse. Very sad in this day where we struggle as women for our choices and our rights.