JTF (just the facts): Published in 2019 by Skinnerboox (here). Hardcover, 22.4×33 cm, 188 pages, with 84 color reproductions. Includes an essay by the artist. In an edition of 600 copies. Design by Justin Sloan and CH-RO-MO. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Sunsets belong on the short list of most overworked photographic subjects. Even at their most jaw droppingly spectacular, where pinks, purples, oranges, and golds wash over a dappled sky in an ever changing dance of color and pattern, photographs of sunsets never quite capture the immensity of the moment. It’s an entirely human thing to revel in the slowly dropping sun and the quiet end of the day, so much so that we all try to make pictures of these wonders. But even in all their variety, images of sunsets almost always feel like stock platitudes – we want to be amazed by them, but the photographs are inevitably so predictable that we hardly even need to look at them to understand their message.

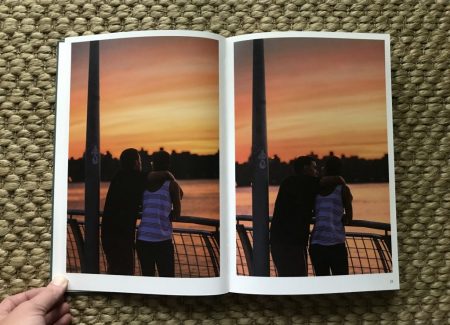

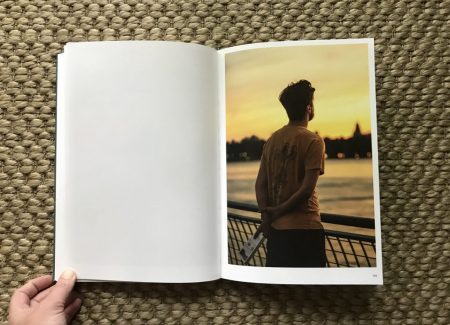

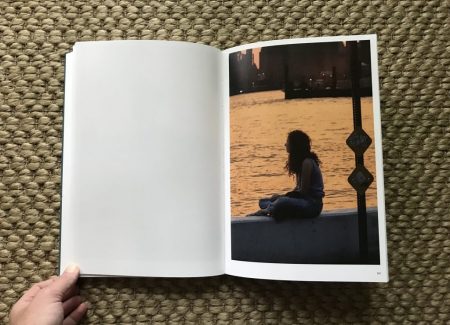

All of the photographs in Matthew Spiegelman’s photobook Transmitter are sunsets, but their primary subject isn’t what’s happening in the sky. Instead, Spiegelman turns his camera toward people watching the meditative drama taking place, in a sense reversing the usual balance of viewer and viewed. His photographs are attentive, indirect portraits of these strangers, where the sunset is a backdrop, an afterthought, or simply a nearby spectacle available for collective enjoyment.

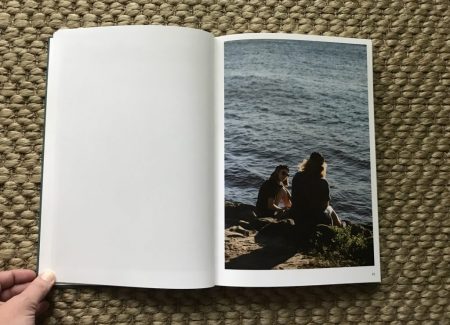

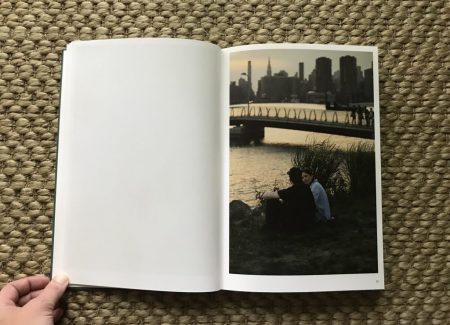

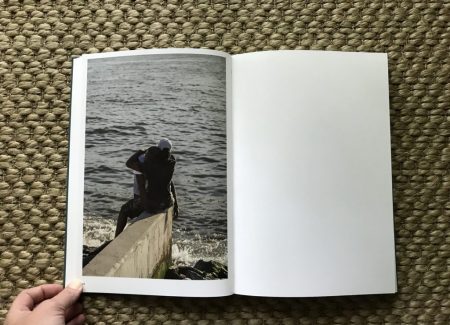

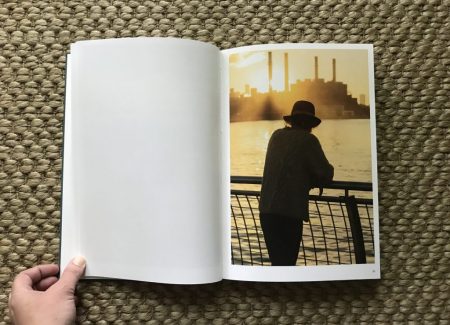

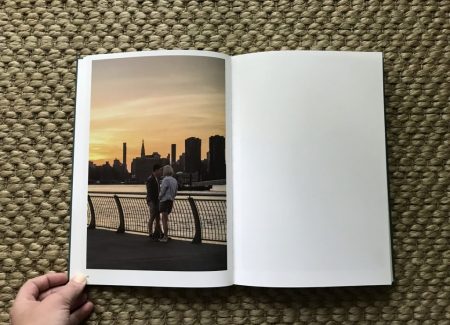

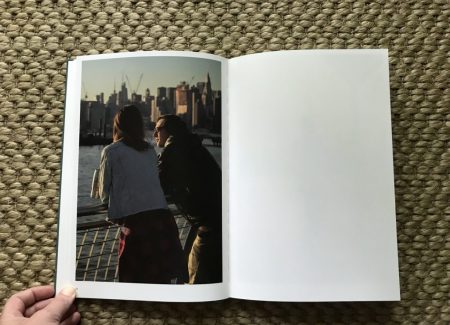

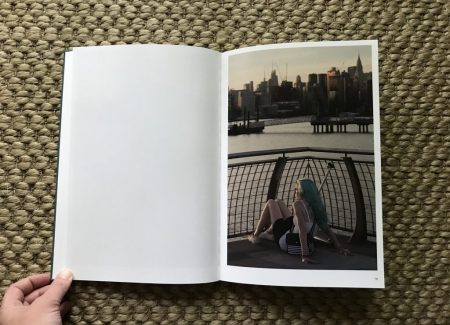

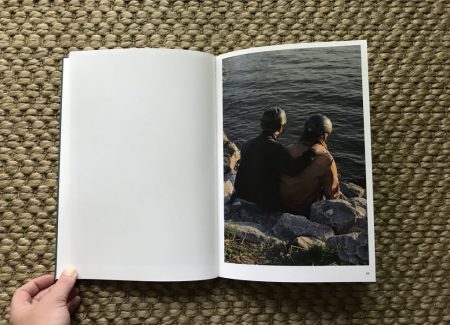

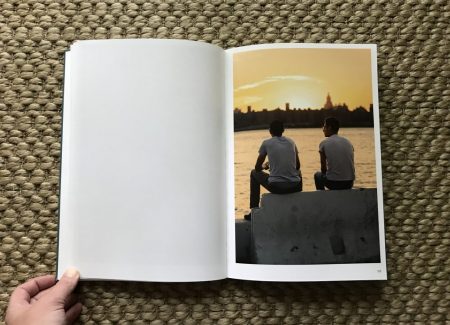

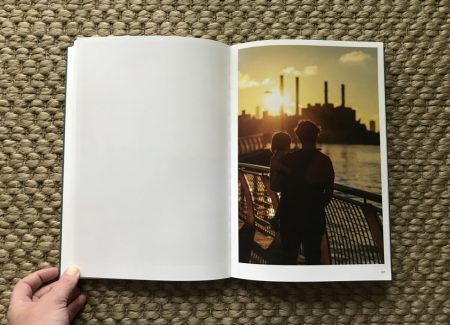

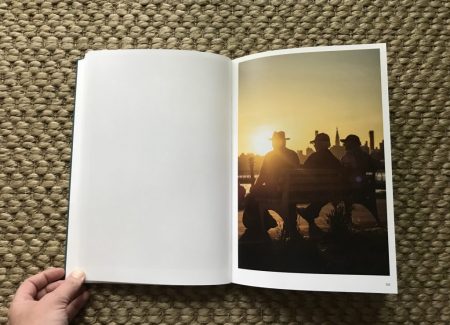

Transmitter takes its name from the place where Spiegelman made his photographs – WNYC Transmitter Park, on the edge of the East River, in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. The park sits where the original radio transmitters sat, and offers local residents a place to walk along the water and look west toward the city, and as it happens, the setting sun. It features concrete piers that jut out into the river, as well as paved paths with railings; there are also ways to get onto grassy areas and the big boulders that sit down on the edge of the water. When the sun is setting, the water sparkles, the city lights start to come on, and the bridges, smokestacks, and skyscrapers in the distance are silhouetted against the changing colors in the sky.

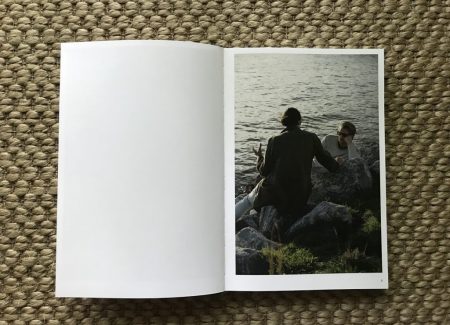

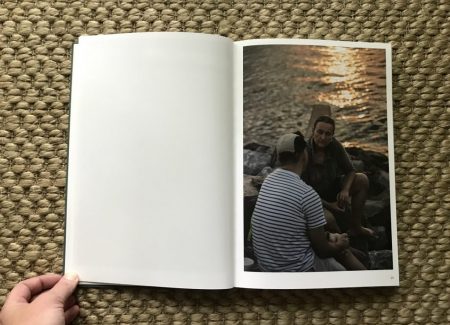

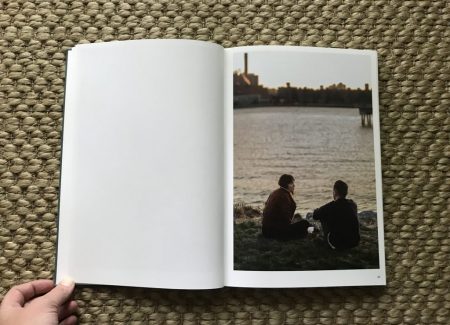

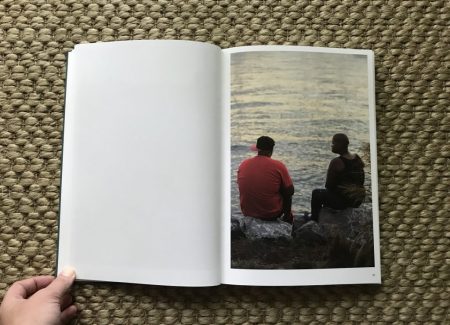

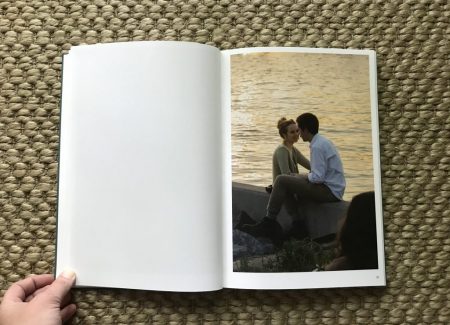

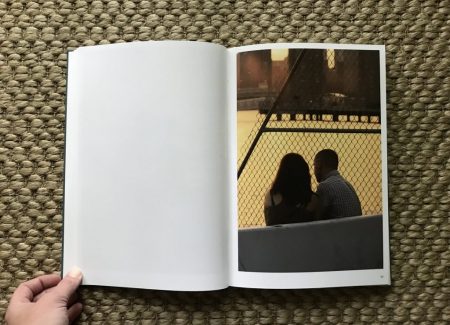

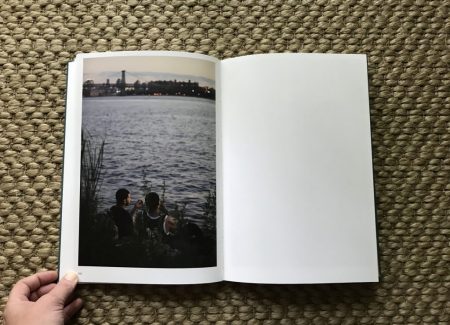

Spiegelman uses the park like a stage set, documenting the small human interactions that take place as the twilight falls. Many of his photographs capture couples, friends, companions, families, and small groups who have gathered along the water, and we follow along as they converse, discuss, smoke a joint, cuddle on the grass, or just watch the sun fall in communal silence. While this description of the pictures might not sound entirely gripping, the photographs themselves are surprisingly intimate and engaging.

Spiegelman pays close attention to the nuances of body language and expression, and his images become a taxonomy of subtle emotion and gestural connection. Intense conversation becomes a whole world of tiny movement, with expectant (or vulnerable) faces turned to talk or listen, brows furrowed, hands clasped, heads tilted, and bodies turned toward or slightly away from partners. Relative nearness and touch are similarly complicated, with a lean back, an arm over a shoulder, a place seated behind, or an embrace signalling closeness, and just a little more space and an wider angle of orientation evidence of distance or misunderstanding that might need some working out. And in a few cases, Spiegelman uses paired images taken seconds apart to document how the moods shift and the gestures change to reflect the drift of the conversation.

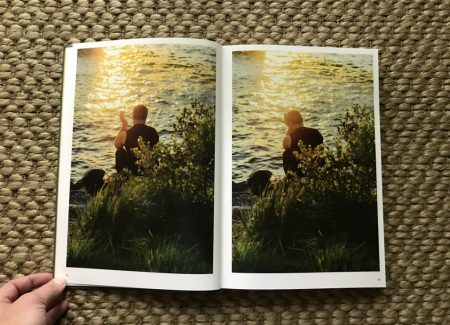

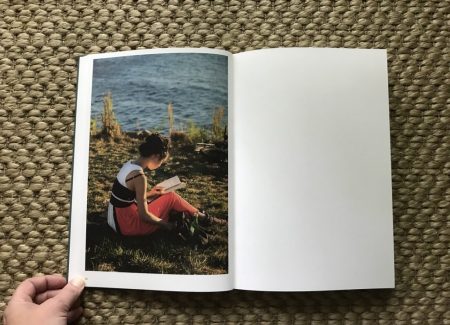

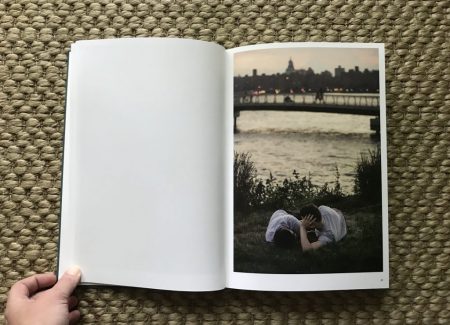

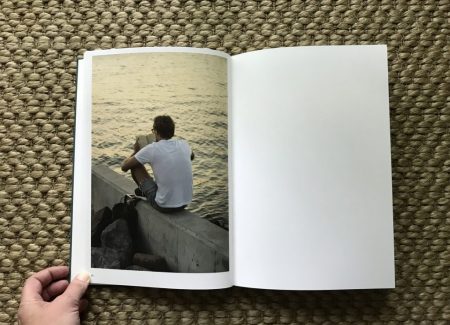

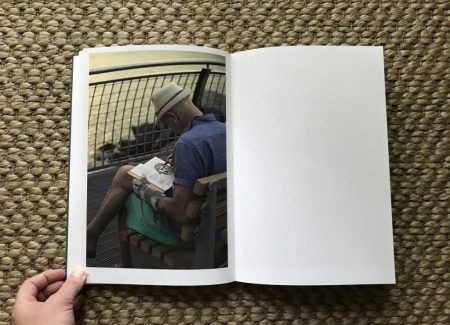

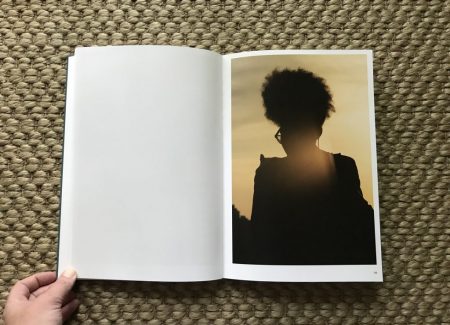

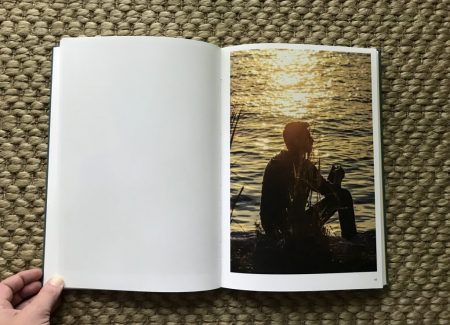

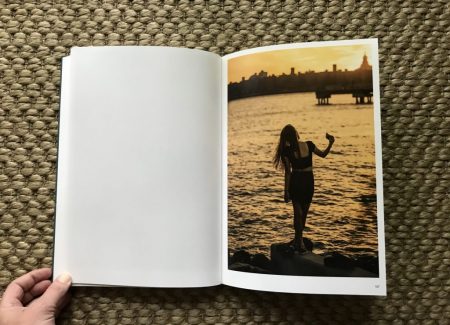

When Spiegelman turns his eye to single people, the dynamics change. Without another person to react to, the solitary visitors largely turn inward – quietly watching the sun set, listening to music, reading a book, or just sitting and thinking. Reduced to silence (unless they talk to themselves, which a few do), they entertain themselves by drawing, taking selfies, drinking coffee, checking off a to-do list, and in one more eccentric case, even smoking a pipe. Here the sunsets are the available partner, and Spiegelman does more compositionally with flares of light, silhouetttes, reflections off the water, and the available architecture of the railings and piers, and his portraits show us more contemplative moments, where a person wrestles with her or her own demons (or perhaps her blowing hair).

With just a few exceptions, Spiegelman stands behind and above his subjects as he is making his photographs, so they generally form a layered arrangement with subject and the rocks/boardwalk in the foreground (at the bottom) and water/sunset in the background (at the top). The design of Transmitter amplifies this arrangement, with large, vertically oriented images presented with just a small amount of bordering. The result is a photobook that feels tall and expansive, with photographs that are framed to draw us into their subtleties, with the color cycle of day to night repeated several times.

It’s not easy to discover a credibly new entry point into the diverse lives of contemporary New Yorkers, but Spiegelman has found just such a doorway in Transmitter. With a physical setup that allows him to observe without intruding, the park offers a place to see New Yorkers with their guard down – at rest, relaxing, or connecting with friends and loved ones. The photographs feel both genuine and consistently insightful, catching both quirks and repeated patterns, all underneath skies that can only be called beautiful. It’s a vision of New York where people of all kinds appreciate the easy grandeur of common experiences, and take advantage of the city as a shimmering backdrop for the rhythms of their individual lives.

Collector’s POV: Matthew Spiegelman does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).