JTF (just the facts): Published by SPBH Editions in 2015 (here). Hardcover, 160 pages, with 91 color and black and white photographs. In an edition of 1000 copies (numbered and signed). Includes texts by the artist. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: While political revolutions are by definition uniquely full of emotion and energy, often with liberal doses of anger and violence, photographs of revolutions often look remarkably similar. Familiar photojournalistic conventions and subjects create repeated patterns and storylines, regardless of time period, geography, or left versus right political slant – there are images of mass rallies and protestors, passionate speeches and charismatic leaders, sit-ins and camp outs, conflicts and injuries, fear and repression.

All of the photographs in Matthew Connors’ Fire in Cairo were taken in Egypt between January and June 2013, roughly during the time that demonstrators returned to Tahrir Square (marking two-year anniversary of Hosni Mubarak’s overthrow) to protest against the new government of Mohamed Morsi and what was perceived as his abuse of power. Like many books that have come out of Egypt chronicling the recent struggles there, Connors’ photobook investigates the unsettled state of political uncertainty in Egypt, but it does so without falling back into the usual ruts of documentary photography. His book offers an artistic perspective on the revolutionary struggle, and an indirect portrait of both the events themselves and the people who took part.

The first clue that Connors’ photobook is something different is that it opens backwards – the book begins from the end, although there is no obvious indication of this and the flow actually works both ways. A short fictional writing by Connors (inspired by Donald Barthelme) sets the atmosphere for the visual narrative. The text also flows from right to left, perhaps as a reference to Arabic script and culture.

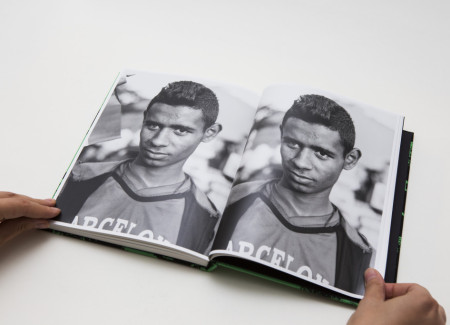

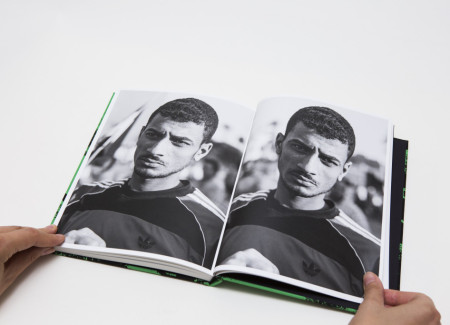

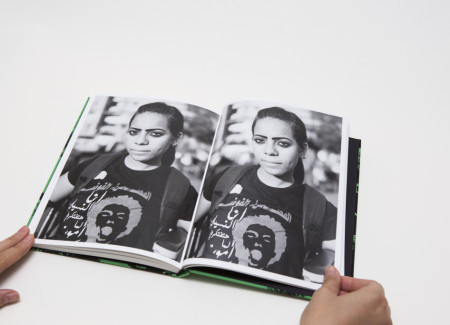

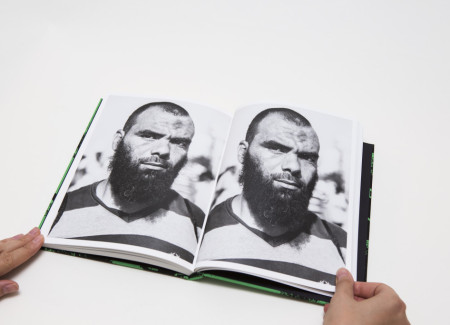

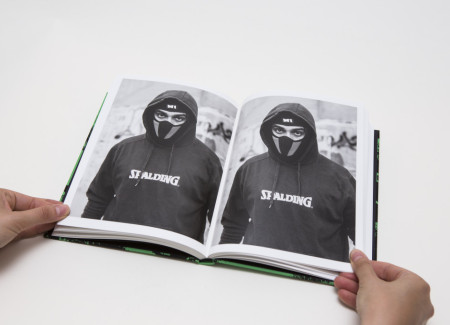

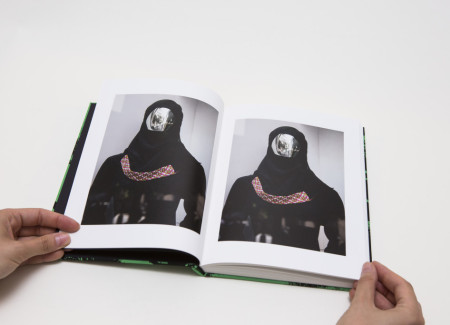

The first image in the book is a black and white portrait of an elderly Arab man with a gray beard; he has a calm and confident gaze as he looks straight at the camera, and seems like the kind of man you might visit if you needed some life advice. As the pages turn, we see other portraits of Egyptians who took part in the revolution, and they are all different: young and old, men and women, and coming from various political beliefs (we can tell this from their clothes, signs, mood, and gaze). There are two portraits of the same person on each spread – some of them appear to be identical, others might have been taken a few seconds apart capturing a slight shift in posture or look (sometimes it is hard to tell, are opinions static or changing?) Ordinary looking young people mix with those in masks and helmets, while a young woman holds a stack of petitions calling for Morsi to step down and demanding new elections. In these pictures, Connors seems more interested in the tiny nuances of expressions on both sides rather than the momentous events; his attention is fleetingly turned away, at a personal level, where uncertainties flash across faces in an instant.

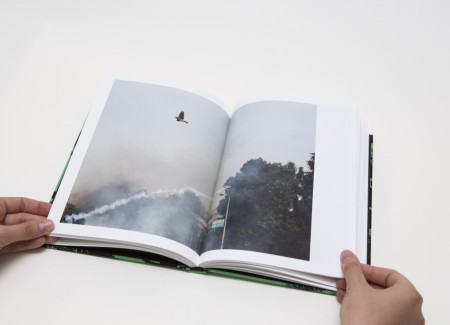

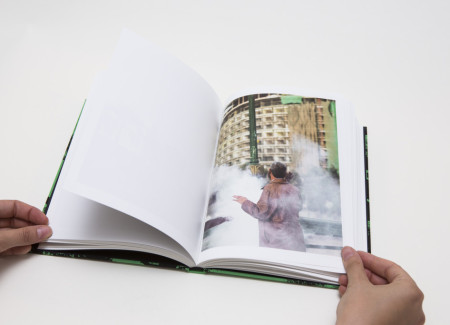

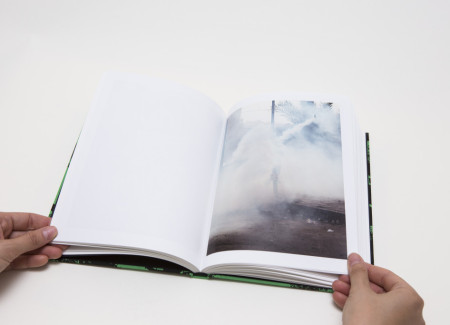

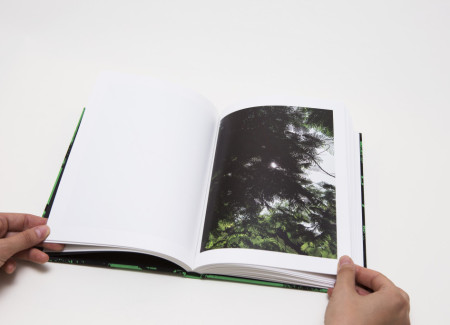

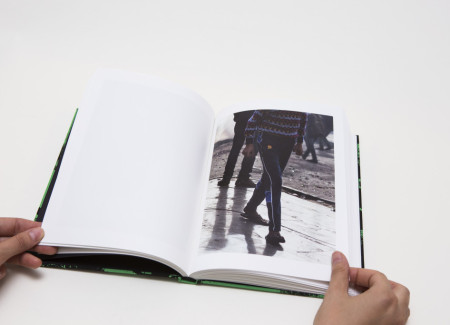

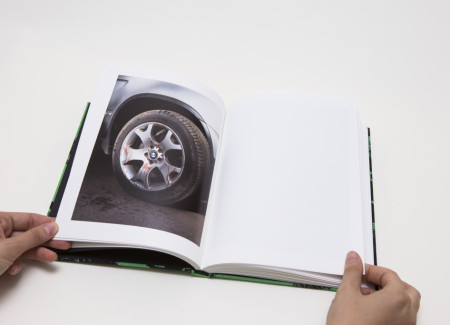

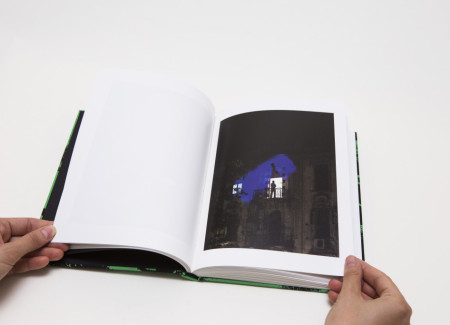

After about a third of the book, the dynamic and the narrative changes, signaled by an image of rich fire flames on a black background. This part of the photobook moves away from human faces and looks to image fragments and unexpected details of the developing story: green lights of lasers moving through the darkness, shadows, a close-up of a car tire covered by blood stains, clouds of tear gas passing through the sky, flares of sunlight through the green leaves. Some add a sense of the wartime surreal – an image of the helicopter flipped upside down or tails of grenades as they form abstract shapes in the sky.

There are no recognizable images of conflict here; it feels as if Connors’ camera is deliberately looking away from the action scenes, as though trying to see the reflection rather than the primary source. His visual metaphors give us hints about the resistance, but they don’t necessarily provoke an instant response or understanding. Fire in Cairo embraces the unavoidable chaos of the historical situation and mixes it with inevitable confusion of an outsider, offering a parade of complex associations and personal interpretations. The book is open ended in this way – the manner in which we as readers connect the images into a wider narrative is influenced by our own knowledge and sensibility, allowing various readings and avoiding one explanation or “answer”.

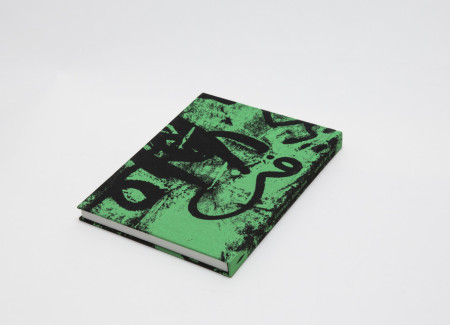

With a silk screened cover in fluorescent green and black and a pattern that evokes both Arabic calligraphy and rough graffiti, the exterior of this photobook definitely grabs attention. Apart from the eye catching cover, the book’s design and layout are rather pared down and elegant, forcing us to focus entirely on the visual narrative. The photographs themselves vary slightly in size and have a thin white border around them, but there are no captions to provide context; it’s a spare and generally unadorned series of images. In general, the book design and construction serve this narrative well, as they drive the viewer back toward looking closely at the pictures and to pondering the rest of the action taking place off camera.

In an interview with the British Journal of Photography, Connors said, “I always knew I wanted to do a book, and it definitely changed the way I was thinking about photographing”. That’s actually a fascinating admission, in that the photobook form and its particular capabilities (sequencing, sizing, momentum etc.) led Connors to make different decisions about the story he wanted to tell than he might have made had he been centered on making prints or gallery exhibits. In the end, he’s created a very indirect and experimental narrative here, one that wanders through but never directly faces the revolution at hand. He’s settled in at the border of subjective documentation and poetic presentation, seeing the conflict as a interrelated collection of component parts rather than an overarching whole.

Collector’s POV: Matthew Connors does not appear to have gallery representation at this time. Collectors interested in following up should likely connect directly with the artist via his website (linked above).