JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by Thames & Hudson (here). Hardcover, 10.8 x 10.7 inches, 172 pages, with 100 black-and-white and 20 color reproductions and 5 panoramic foldouts. Includes notebook entries and an introductory essay by the artist, transcribed interviews and spreads of shorter quotes, mapping app screen shots, and a table of statistics. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: For photographers who head out on the road to discover their photographs, the end point of their journey is most often an exhibition or book that gathers together an edited selection of images from the trip, generally sequenced into a narrative that represents the larger themes or stories that the artist wants to communicate about what he or she found or learned. What perhaps started out as a wandering search or even a chance-driven journey is later shaped and arranged into something that feels (in retrospect) altogether deliberate and intentional, with much of the messiness and randomness of the actual art-making (and thinking) process largely stripped away. Along the way, many if not most itinerant photographers make schedules, take notes, make test snapshots, write journal entries or reflections, record conversations or interviews with the people they meet, and gather up and keep all kinds of paper ephemera and resonant objects. This accumulated stuff can provide important context for the photographs, and in many instances, helps to shape both the eventual story that gets told and the language that is used to tell it.

With the benefit of hindsight, we can now readily appreciate that “American Geography” was the project that cemented Matt Black’s photographic reputation. Published in photobook form in 2021 and accompanied by a touring museum exhibition that same year, it was the summation of more than six years on the road (from 2014 to 2020), with the artist crisscrossing America, moving from one high poverty community or region to another across the nation (his trip took him to a total of 46 states) and documenting the generally overlooked circumstances of pervasive poverty in this country. Mixing documentary rigor with aesthetic compassion and intensity, the project conceptually captured the inverse of the American Dream, making the everyday ground level traumas of being poor in 21st century America more explicit. In mindset and approach, Black’s project hearkened back to the images of the FSA photographers working during the Great Depression, who told powerful visual stories of Dust Bowl failures and rural working-class struggles with unvarnished directness and understated humanity.

American Artifacts is essentially a companion volume to the original American Geography photobook, expanding the narrative to include a wider range of additional source materials. And while it does include a number of unpublished photographs from the first project (including several knockout panoramas on foldouts), the focus of American Artifacts lies in Black’s mountain of accumulated ephemera from those years. As it turns out, during his travels, Black not only meticulously made notebook entries, transcribed conversations, and kept maps, bus tickets, and other supporting information, he also amassed more than 3000 objects that he collected while walking around and making pictures, carefully labeling where and when each one was found.

In unearthing, sorting, collating, photographing, and re-imagining all of this material over the past three years, Black has taken a quasi-anthropological approach to investigating the landscape of ideas and findings that became “American Geography”, shaping the remaining physical evidence into an alternate vantage point or matrixed perspective on the same central subject of poverty in America. In this way, American Artifacts is a photobook that undeniably builds on and complements the original (even though it can photographically stand on it own), adding new layers of complexity, nuance, and interpretation to the primary argument.

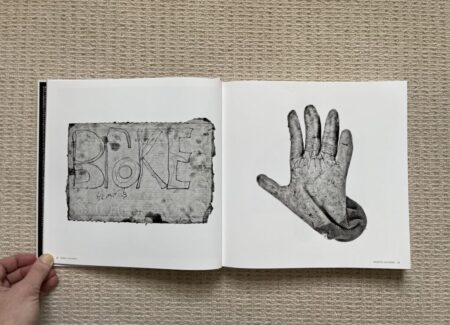

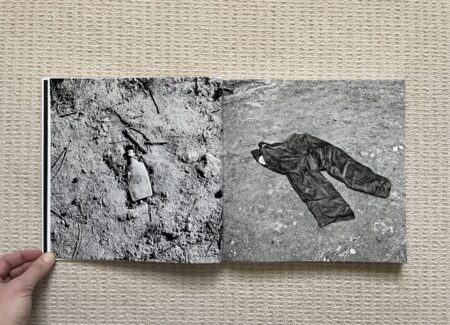

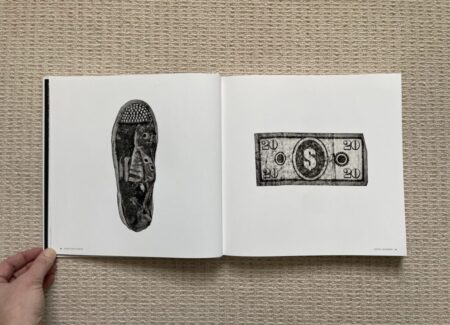

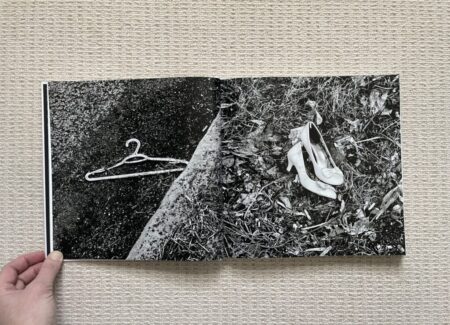

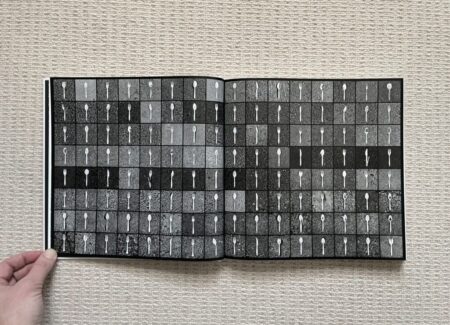

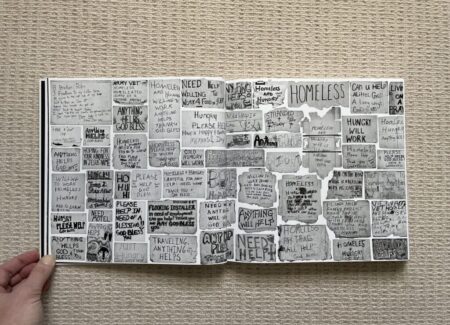

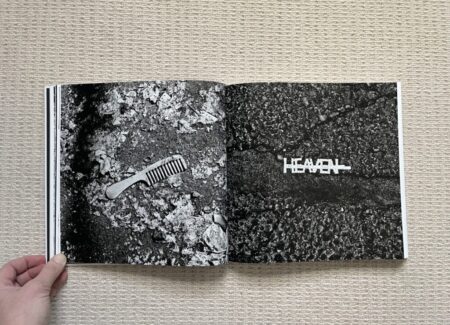

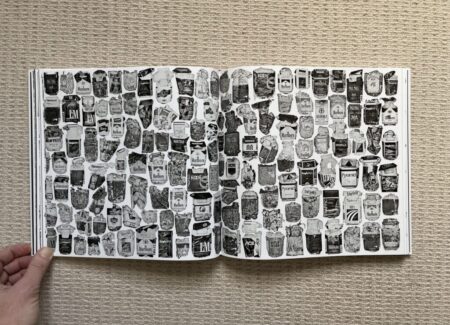

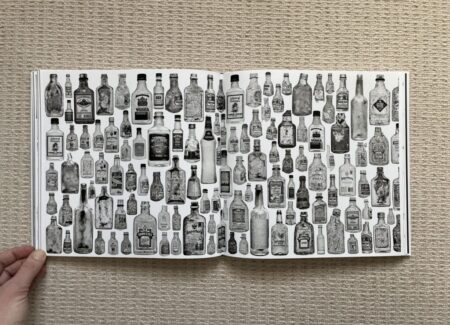

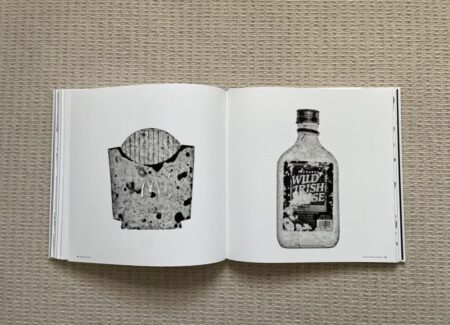

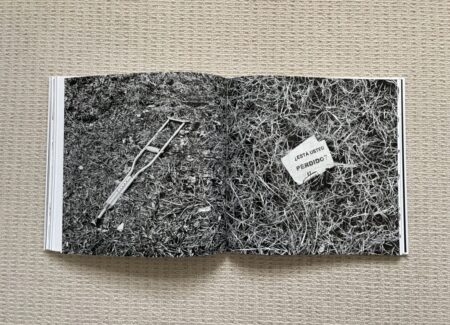

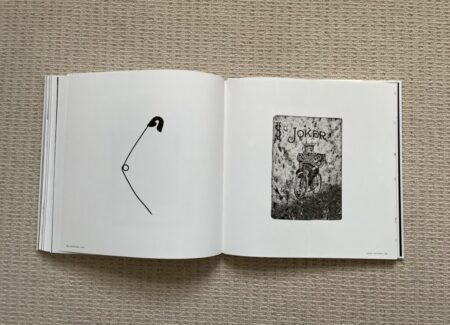

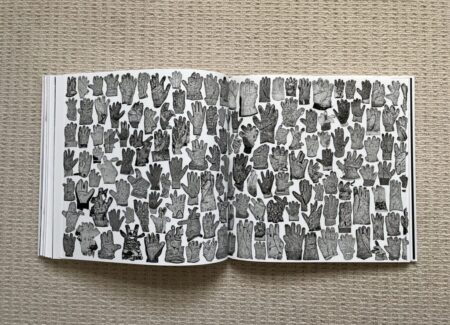

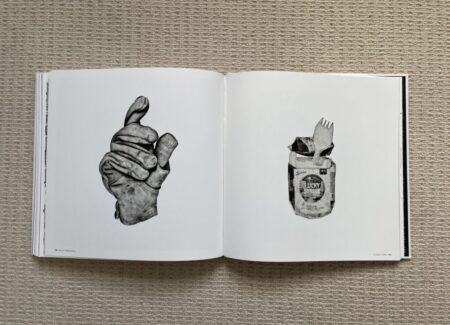

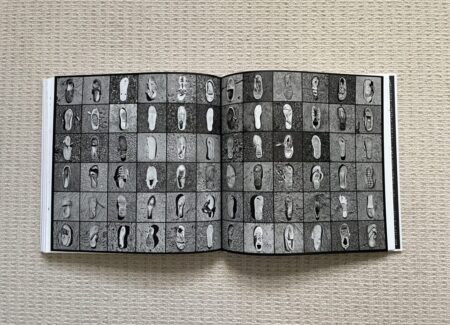

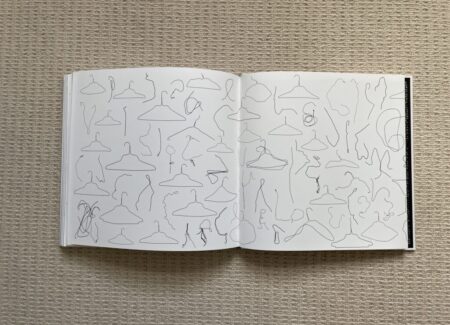

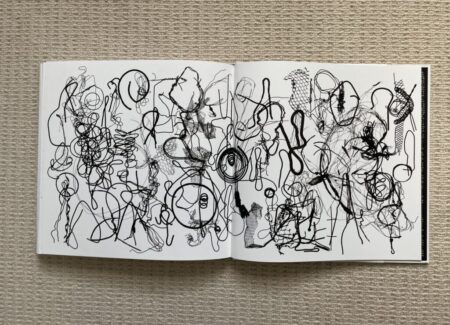

For the most part, American Artifacts is a book of still lifes, albeit in many forms and structures. With echoes of Irving Penn’s images of cigarette butts and mud gloves, as well as his photographs made “underfoot” of sidewalk litter, Black has used a range of different strategies to document his archive. Some objects seem to have been captured in situ, sitting in the dirt, on grass, against cracked concrete, or in the gutter, either as he found them or cropped and isolated into more formal positions; similarly, Black’s images of graffiti tags must reflect their original locations. Other objects have clearly been removed from wherever they were found, and set against blank white backgrounds and photographed with flash, creating high contrast black-and-white representations that seem to float against emptiness. Images made with both approaches have then been organized and presented in alternate ways: as single object still lifes, with enlarged presence; as grids or taxonomies of similar items; and as dense collages, where the pictures are tightly arranged together like cutouts with one common backdrop.

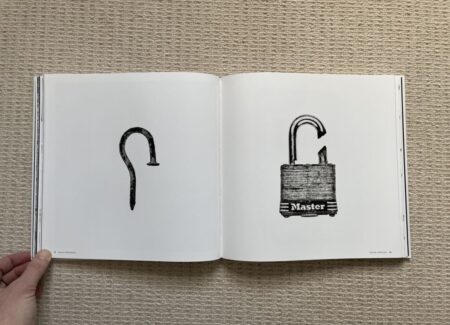

In terms of the actual objects that Black found on his many walks, there are certainly common categories that he came back to again and again. Scraps of wire and hangers, plastic liquor bottles, work gloves, cigarette packs, homeless signs, plastic forks and spoons, and single shoes and sandals seem to have been his most repeatedly collected items, with many of these items gathered in dozens if not hundreds of examples. More singular items, with particular resonance in many cases, include a HEAVEN barrette, a cut padlock, a pair of broken sunglasses, a single crutch, a losing Set for Life lottery ticket, some playing cards, a fake $20 bill, a bent nail, a half-played Halloween word search puzzle, and a flyer in Spanish asking está usted perdido (are you lost?). Black called the saving of these objects a kind of “sidewalk archeology”, with the litter at his feet providing an unexpected wellspring of truth and a symbolic visual language with which he could further interrogate the the lives of the American poor.

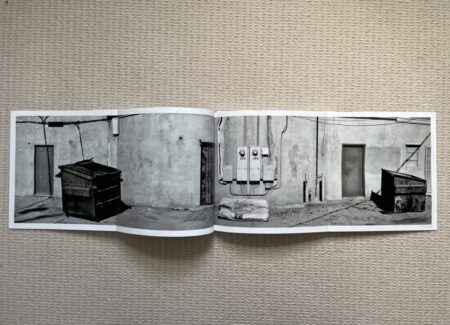

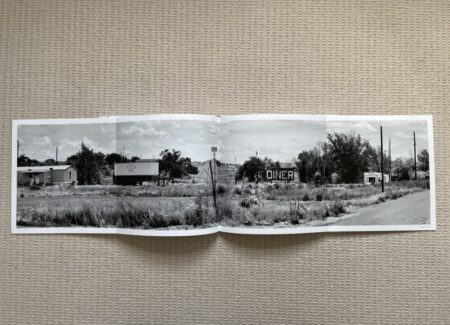

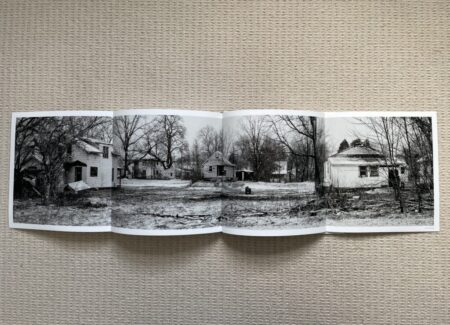

Structurally, American Artifacts is organized into a series of refrains, with each section comprised of the same elements in the same order. After endpapers that feature the hand written names of towns with concentrated poverty across America (a list which is later given more statistical heft in a table near the end of the book) and an introductory essay by the artist, the sections begin, each starting with a series of journalistic notebook entries filled with short anecdotes and personal stories. These are followed by a few previously unpublished photographs from the original “American Geography” project, and then several single still lifes. Fuller interviews with single individuals then provide a text-based interlude in each section, followed by more single still lifes, a full spread grid of categorized still lifes, and a spread of quotes from various individuals arranged to float across the spread. Each section ends with more single still lifes, several collaged spreads of categorized objects, and a double page foldout housing a panoramic photograph. This larger pattern repeats a handful of times, creating a sense of anticipatory rhythm in the progression of the page turns.

As much as many of the collaged, gridded, and even single still lifes are visually powerful, Black must have felt like they couldn’t quite tell the story of American poverty all on their own. The dense collages of work gloves, homeless signs, and liquor bottles are particularly strong (and would likely be jolting if printed extra large for a museum setting), as are the wire studies that edge toward the high contrast look of photograms, and many of the single still lifes (the lonely shoes, the broken comb, and the many solitary eating utensils, for example) deliver a strong sense of intimate hollowness and desperation. But they need the addition of the text-based notebook entries, interviews, and pull quotes to broaden their storytelling capability, and to put voices in our heads that we can imagine as former owners of these objects.

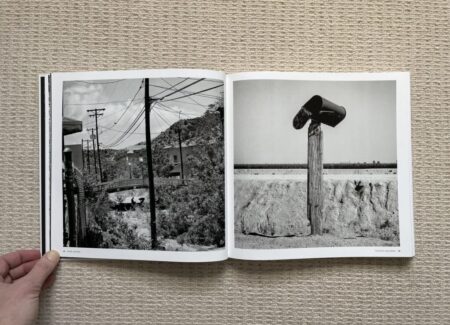

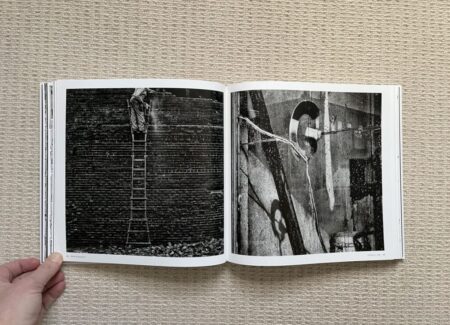

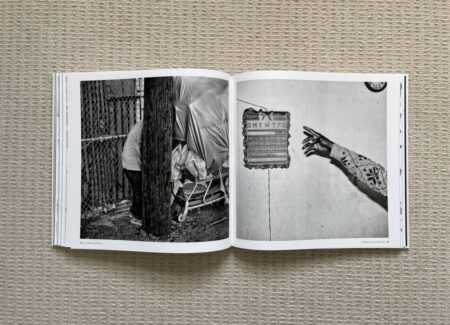

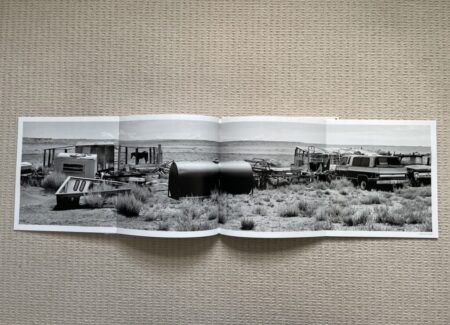

Earlier in his career, Black’s use of extreme contrasts of light and dark made some of his images almost too intense, which in a way diluted their ability to evoke more nuanced reactions. But the few photographs of interior and exterior locations and landscapes included in American Artifacts find a much better balance, with standout images of twisting barbed wire, two silhouetted figures under a bridge, a mailbox knocked off its post, a brick mason on a tall ladder, a man hidden behind a telephone pole, and an extended arm pointing at a wall calendar all delivering memorable power and compositional elegance. Several of the wide panoramas are similarly excellent, including an alley view with dumpsters and a stained mattress (in Blythe, California), a desert sweep populated by a water tank, a horse in a corral, and a jumble of various trucks, trailers, farm equipment, and sheds (in Black Falls, Arizona), and a desolately quiet winter scene filled with dark trees and white houses (in Flint, Michigan.)

In weaving together all of these disparate photographic approaches and humble archival objects, Black has crafted a richly compelling parallel companion to his original “American Geography” project. In many ways, American Artifacts is even more personal, as we can feel the human touch and warmth that still inhabits the discarded objects, and their symbolic representation of the trials of life in poverty in America makes the issues (and challenges) more tangible and less arms length and abstract. American Artifacts is no less critical or incisive than its predecessor, but its angle of attack is more varied. Hopefully soon, some major institutions will take up the task of thoughtfully integrating these two halves into a single more comprehensive whole, thereby making the combined presentation all the more compelling and urgent.

Collector’s POV: Matt Black is represented by Robert Koch Gallery in San Francisco (here) and Magnum Photos (here). Black’s work has very little secondary market history, with just a handful of lots coming to market in the past decade. Prices for those few lots have ranged from roughly $6000 to $12000.