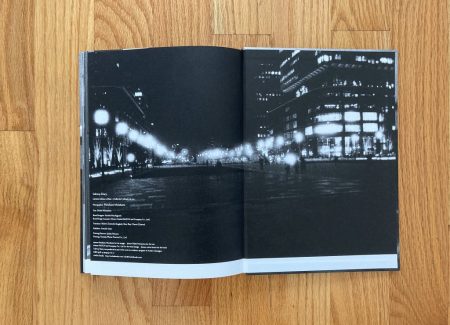

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2020 by Roshin Books (here). Hardcover, 144 pages, with 100 black and white reproductions. Includes texts by Daido Moriyama and the artist. In an edition of 800 copies. Design by Satoshi Machiguchi. (Cover and spread shots below.)

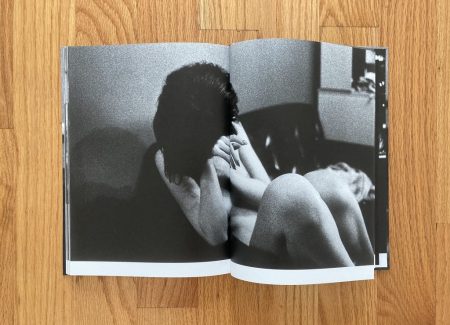

Comments/Context: The Japanese photographer Masakazu Murakami has been photographing the Tokyo subway for over two decades now, taking his first photos while he was still a student. He carries his camera with him everywhere, and shooting while on a subway helps him get through the day and deal with his anxiety and oscillating moods. He compares making photographs to “writing a diary that I would never read again or show anyone.” But recently, during a residency at the Tokyo atelier chataigne, he focused on reviewing and organizing this body of work. The photographs, taken over many years, show how fast the city has been changing. This year, with the end of the Heisei era (the thirty year reign of Emperor Akihito) and as Japan enters a new period, Murakami saw a historical moment to release his series. Earlier this year, the photographs were published in a photobook by the independent Tokyo-based imprint Roshin Books.

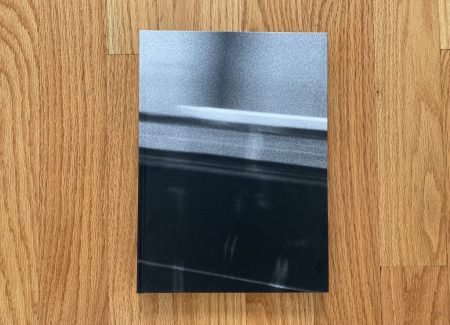

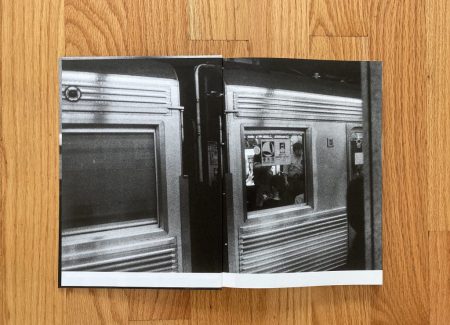

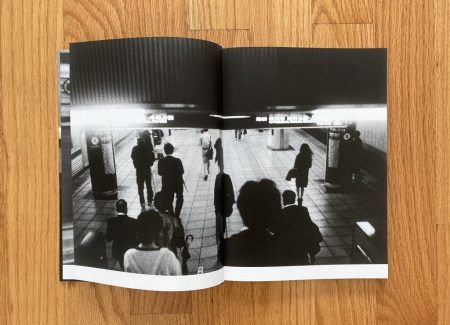

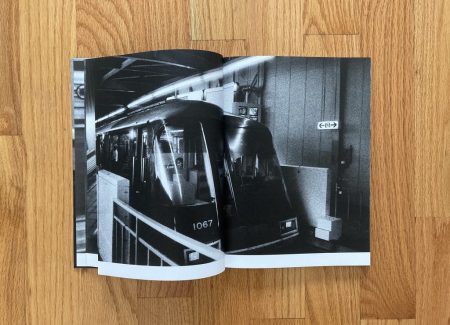

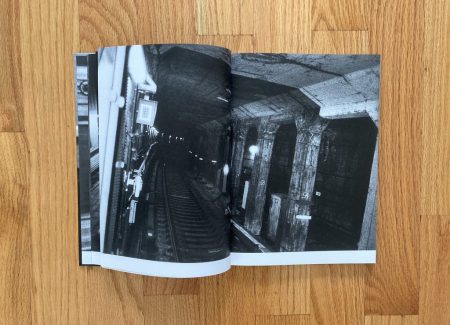

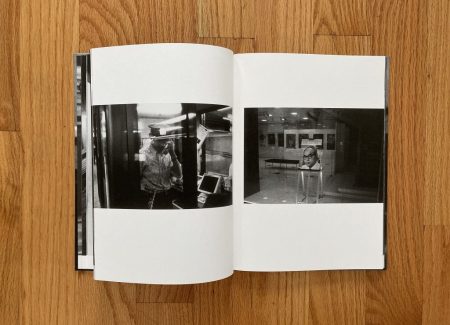

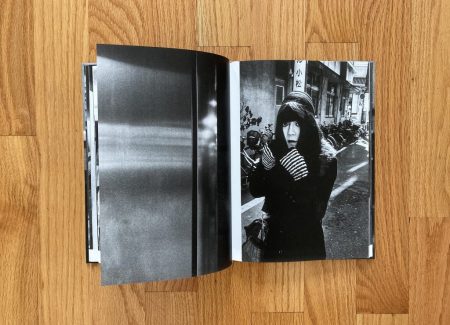

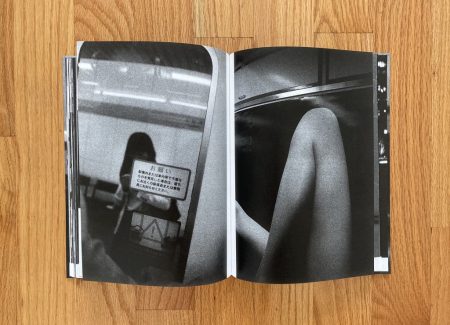

Titled Subway Diary, the book is medium sized; a grainy black and white photograph, perhaps a close up shot of a passing by subway car, envelops the book, and there are no other texts or design elements. A photo of a subway car shot front the platform appears on the endpaper and serves as an introduction to the visual flow. Most of the photographs are full bleed, with a thin white border at the bottom, or just in a few cases, the border is in the gutter. The images coalesce into a consistent visual narrative, immersing the viewer into the atmosphere of the Tokyo subway. Murakami was influenced by many of the post-war Japanese photographers, particularly Daido Moriyama. Moriyama wrote an essay for the book, which is elegantly printed on a separate insert (in white against a black background).

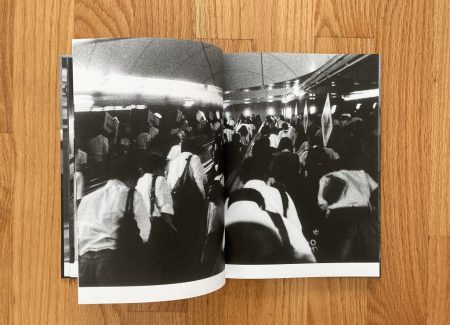

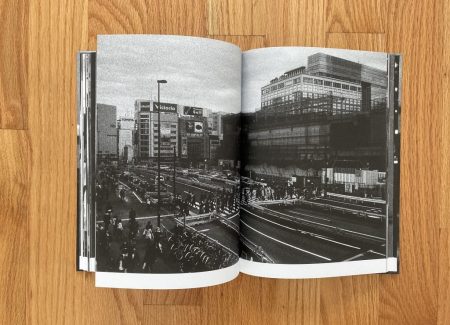

The first full-fledged subway line began operating in Tokyo in 1927. Today the sprawling system has close to 300 stations and it is the world’s busiest underground network, known for its notorious rush hours. About 8 million people take the subway daily, although, virus countermeasures have eased congestion on the trains somewhat this year. Commuters crammed into the Tokyo subway, pressed uncomfortably against glass, were memorably captured by Michael Wolf, and Murakami’s atmospheric photographs, often grainy and blurry, offer an additional vantage point on a well-known slice of Tokyo’s hectic and busy daily life.

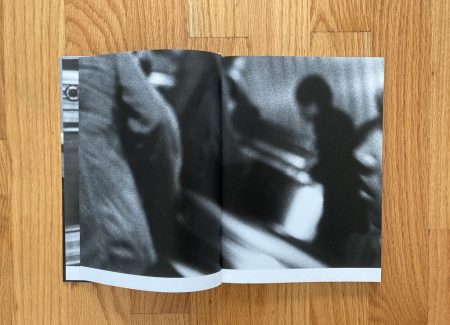

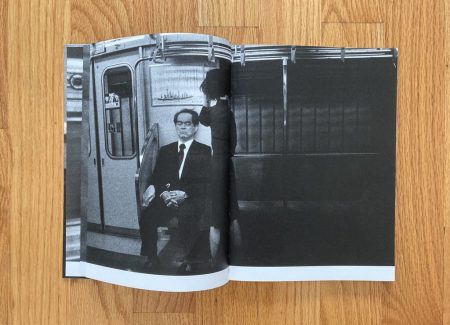

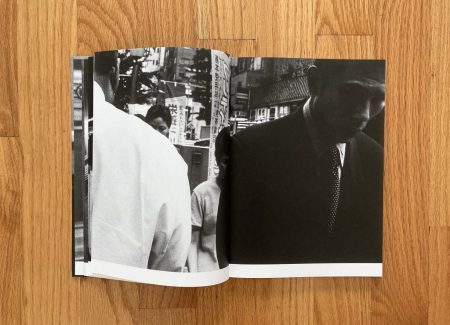

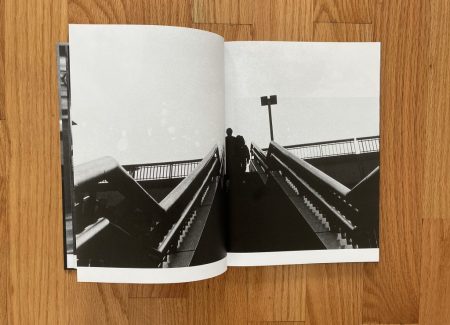

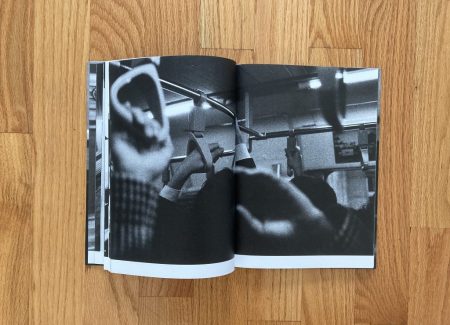

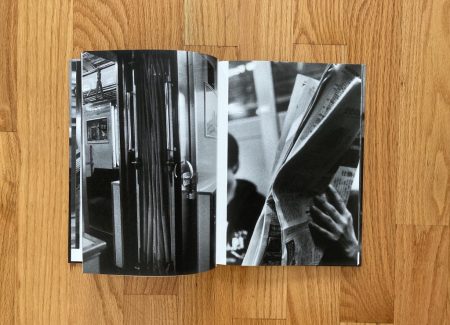

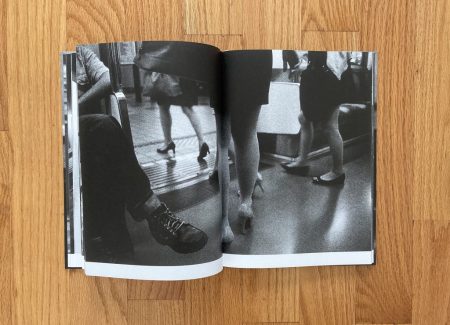

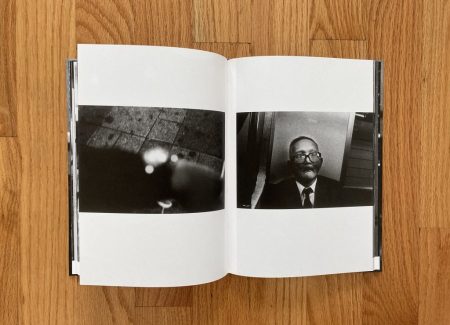

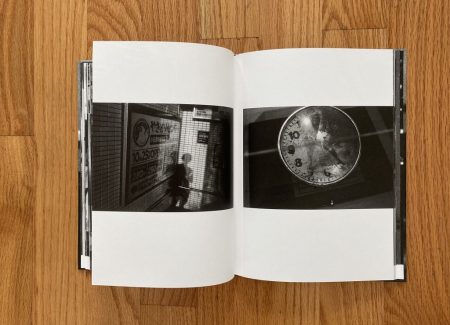

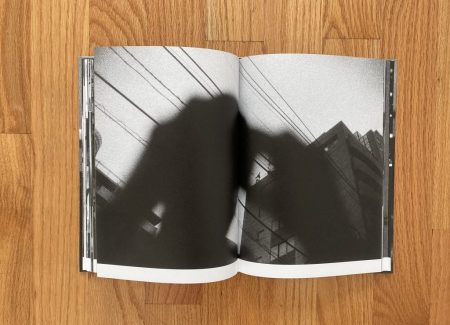

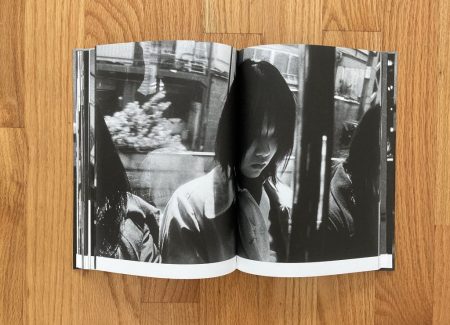

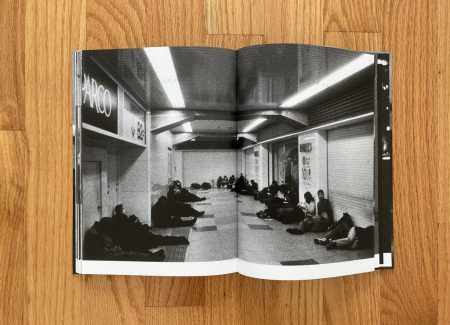

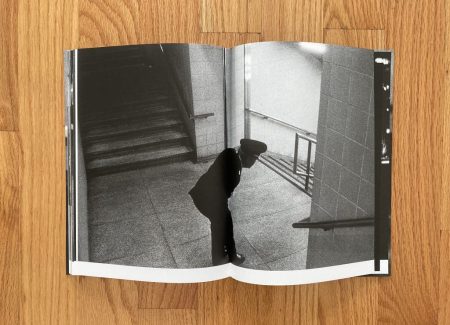

The opening sequence of the book sets the mood – a fleeting shot of people in a rush, a middle-aged man in a suit sitting with his eyes closed, the head of the subway car approaching the station, a dark station tunnel with supporting columns, signs and direction arrows. As a commuter himself, Murakami gets close to people, reflecting the tight and busy environment. In one image, the silhouette of a man walking takes up half of the spread, creating a feeling that we are right in the middle of a crowd. A few spreads later, a shot at the level of people’s heads shows a row of hands holding on to hanging straps. In another picture, we are on a crowded escalator moving up, with mirrors on each side making it look even more packed with people. From intense mornings and quiet evenings to striking in-between moments, Murakami captures the diverse rhythms of life underground.

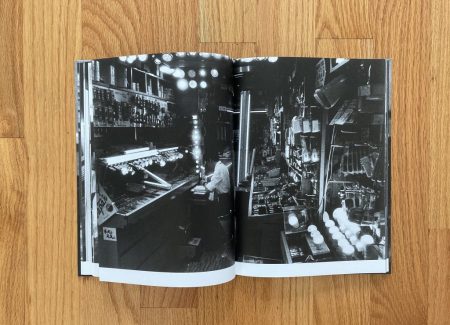

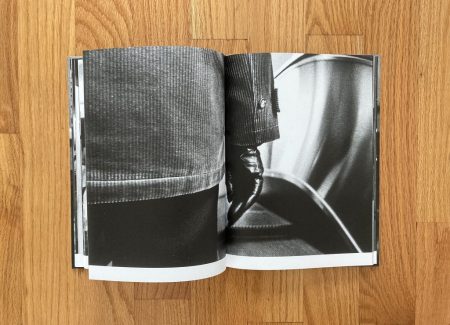

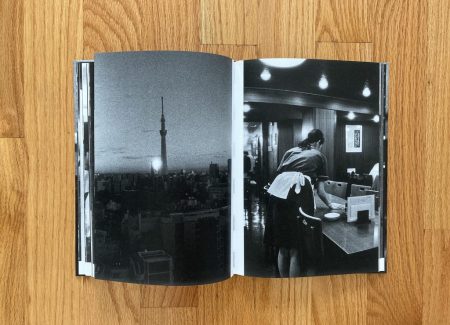

As the visual narrative moves forward, there are photographs outside the subway, as if we are getting off at one of the subway stops. A shot of the Tokyo Skytree is paired with an image of a waitress wiping a table, as seen through the window. A full spread captures a man working in his shop tightly yet neatly packed with bright lamps, light bulbs, switches and some other tools, in a way resembling a subway scene in rush hour. And then we get back on the subway. There are plenty of notable images capturing unique moments of smart framing: two people walking up the stairs leading to an open air platform; a few spreads later, a bottom of a man’s jacket as its ribbed texture matches the steps of the escalator; and close to the end, a man in a uniform bends over as he looks down the stairways leading to the subway.

Marukami’s photographs are blurred, and often out-of-focus, influenced by visual sensibility of the late 1960s to the mid-70s. Just like Provoke photographers, he moves beyond the question of what to photograph, focusing on the essential nature of photography itself. Marukami’s shots variously reference Daido Moriyama, Shomei Tomatsu, Masahisa Fukase, and Takuma Nakahira, yet he has found his own visual language, filled with nuance and understated expressiveness.

In the end, the subway, and the related scenes outside, are simply an available subject for Murakami’s active attention – he captures the mundane in front of him, revealing how extraordinary it actually is. The result is a dreamlike and even intimate streetwise portrait of his hometown. Subway Dairy depicts the subway through a lens of very personal daily observation, and with its vision and sensitivity, captures a place and time we might see but overlook.

Collector’s POV: Masakazu Murakami is represented by in)(between gallery in Paris (here). His work has not yet found its way to the secondary markets, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

The subway has always been such a magnet for photographers . Love he fact that this work was produced over such a long period of time. You can also see the Daido influence here. Great review Olga.