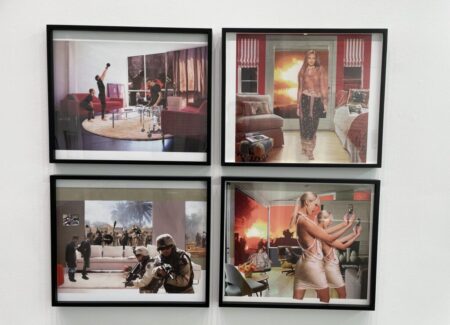

JTF (just the facts): A survey of photomontages, installations, and videos, on view in the main gallery space, the entry area, and the smaller side gallery. The photomontages are generally framed in black and unmatted. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 15 photomontages (from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series), 2003, 2004, sized 20×24, 24×20 inches

- 2 photomontages (from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series), 2008, sized 30×40, 40×30 inches

- 2 photomontages (from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series), 2008, sized roughly 30×53, 30×102 inches

- 1 photomontage diptych (from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series), 2008, each panel sized roughly 30×39 inches

- 1 installation with hanging plastic panels printed with quotations by Hannah Arendt, 2006

- 2 inkjet prints on vinyl, n.d., sized roughly 40×60 inches

- 5 photomontages (from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home), c1967-1972, sized 20×24, 24×20 inches

- 5 photomontages (from the series House Beautiful: The Colonies), c1969-1972, sized 20×24, 24×20 inches

- 4 photomontages (from the series The Rewards of Money), c1987-1988, c1987-1988/2022, sized 20×24, 24×20 inches

- 5 photomontages (from the series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain), c1966-1972, c1987-1988/2022, sized 24×20, 20×16 inches

- 1 installation of color photographs, text, photocopies, 1993, sized roughly 138×138 inches

- 1 four-channel video installation, 2012-2025, 32:30 minutes, 28:09 minutes, 39:24 minutes, 30:42 minutes

Comments/Context: During times of social and political upheaval in America, certainly in the past century, it has often been our artists to whom we have turned for the incisive truth telling and unflinching satire that has helped us to discover perspective on the tumultuous moments at hand. And so as we find ourselves in yet another period of disorienting disruption, it’s not surprising that the work of artists like Martha Rosler feels particularly prescient and relevant once again.

Rosler had a decently comprehensive retrospective of her work during the last Trump administration, in 2018 at the Jewish Museum (reviewed here), so the idea that her work resonates with the rhythms and complexities of these times has already been explored in some depth. This gallery show, her first with Galerie Lelong, reprises many of the projects shown there, with a particular emphasis on Rosler’s photomontages, reaching from the mid 1960s to the end of the 2000s. The show is centered on a full presentation of her recent photomontage series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, New Series (whose last works were made in 2008), supported by selections from several other earlier photomontage projects as context.

This recent series builds on an initial idea Rosler had back in the late 1960s, in the context of the Vietnam War. Starting with images drawn from high end home decor magazines (largely aimed at women), Rosler interrupted the stylish scenes of living rooms, summer cottages, and outdoor patios with photojournalistic images drawn from the headlines. For their time, the photomontages were just convincing enough to make viewers do a double take – wait, there are tanks and a rubble strewn street outside the patio window, a weary soldier sitting in the grass outside a tract house, a cowering (or perhaps dead) body lying on the cottage floor, and a Vietnamese woman with an amputated leg wandering around in the living room?

Suddenly, in Rosler’s world, the horrors of war were intermingled with middle class life, in a way that felt altogether strange and incongruous. In a sense, her composite images offered nowhere to hide, or to passively avoid confronting the grim realities of the war. They also liberally mixed together the domestic and the military, making home life a literal war zone; for many, this offered a sharply feminist reading, where the typical male and female spheres of power and influence were jumbled. As seen in a few examples here, these early photomontages have aged well, still delivering a flash of unexpected bite at every turn.

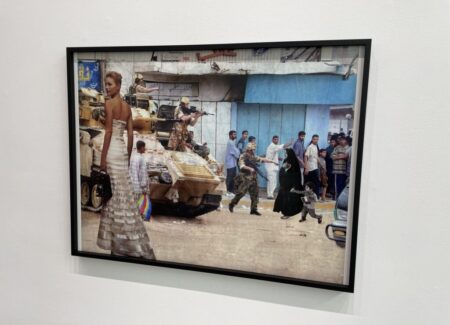

Several decades later, Rosler returned to this artistic framework and made another group of photomontages, this time using the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan as her subject matter. The conceptual structure is essentially the same as before, with sleek interiors and modern furnishings from magazine shoots interrupted by scenes of war, with a few compositions that invert the combination, inserting smiling women and fashion models into broader wartime images of death and destruction. And in general, the power of Rosler’s jarring juxtapositions is largely undiminished – the torture victims on the kitchen appliances, the amputees doing rehab in the living room, the doubled woman taking selfies near the dead children posed on the modern furniture, the hooded captives crouched on the orange carpet, and the fashion models and bloody bodies arranged in the back garden all bring the wars home with uncomfortable intimacy. Rosler’s other reversals are similarly ridiculous, with a woman spraying Febreeze on the furniture in Saddam Hussein’s ruined palace, and groups of smiling women posing with their phones as dense smoke and rocket fire decorate the background. The strongest of these newer photomontages can certainly match the razor-sharp gut-punch irony of any of the earlier pieces, thereby connecting the conceptual structure across time; Rosler literally pulls back the curtain with the same dramatic grace in the newer works, only this time it is fireballs, explosions, tanks, soldiers on patrol, and wailing burka-clad women in mourning who brashly intrude.

Selections from several other earlier photomontage series by Rosler find her expanding the artistic practice in different directions. On the heels of the moon landing in 1969, she grafted images of the moon’s surface and other cosmic starscapes into her appropriated images of suburban home furnishings, imagining a kind of celestial colonization, with stars outside the kitchen window and traffic passing by on the moon. At roughly the same time, Rosler also took feminist aim at images of women in various media sources, swirling together bridal setups, lingerie ads, yoga poses, and nude centerfolds, with women’s bodies and standards of beauty twisted, re-imagined, and undermined. And by the 1980s, Rosler had turned her attention the isolations of wealth inequality, in a series of darkly comic photomontages that repurposed ads for Money magazine, where decaying buildings sit outside the plate glass windows of fancy living rooms and kitchens, and the mass graves of children flank a sunny family garden.

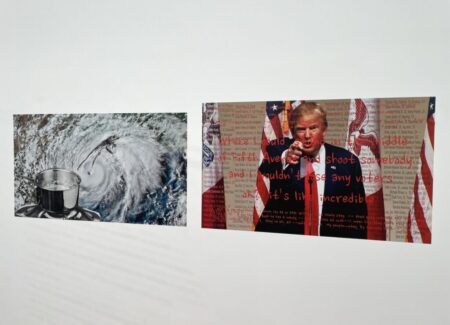

Much of the rest of the work included in this show is more overtly political, generally encouraging us to pay attention and act. The composite image of a frog jumping out of a pot of boiling water set against the swirling eye of a hurricane symbolically asks us to notice what’s happening to our warming climate before it’s too late, and an installation of Hannah Arendt’s incisive quotes about totalitarianism (hanging from clear sheets of plastic in the center of the gallery space) similarly reminds us to see the signs and abuses of authoritarianism as they are taking place all around us. The show ends with video images of various recent protests and marches, almost as a validation from Rosler that this kind of collective activism is the path that needs to be taken.

As I left the gallery, I had the strong sense of hoping that this show will be visited by the roving bands of art students from NYU, Pratt, Parsons, SVA, and others here in New York, and that Rosler’s work will be actively wrestled with by this new generation of art makers. I’d encourage them to pick nearly any photomontage in this show and really consider how it functions, the ideas behind it, the media it appropriates, the techniques used to make it, and why it works (or it doesn’t). Now in her 80s, it’s time for Rosler to pass the baton to the next generation or two, and these younger artists need to understand and process her conceptual innovations and contributions, and then leverage those learnings in their own work. There are plenty of sparks for a young artist to grab ahold of here, and if the tumult of our current political moment is any indication, we’re going to need many more artists who brashly challenge how we think very soon.

Collector’s POV: The photomontage works in this show range in price from $15000 to $70000. Only a handful of works by Rosler have found their way to the secondary markets in the past decade or so, with recent prices ranging between roughly $10000 and $50000.