JTF (just the facts): A total of 39 photographic works, variously framed and matted, and hung against white walls in a series of connected rooms, including the entry area. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 26 gelatin silver prints, 1963/2010, 1965-1966/2008, 1970/2006, 1970/2008, 1971/2008, 1973/2008, 1974/2008, 1975, 1977/2004, 1979/2002, 2001/2008, 2002, 2002/2008, 2003, 2003-2004, 2004, sized roughly 5×3, 5×5, 7×5, 9×6, 11×7, 11×8, 11×11, 11×15, 12×12, 12×18, 13×13, 13×14, 14×10, 14×11, 15×11, 16×12, 17×17, 21×14, 24×20 inches

- 3 gelatin silver print, glass, paint, cardboard, tape, string, and wood frame, 1969/2004, 1984, sized roughly 11×8, 11×14, 14×11 inches

- 9 gelatin silver print, paint, glass, cardboard, tape, string, 1964/2004, 1979/2004, 2001/2003, 2003, 2003/2004, 2008, sized roughly 5×4, 6×4, 7×4, 7×5, 10×11, 15×11, 16×12 inches

- 1 set of 33 gelatin silver prints (“Marriage Cluster”), glass, paint, cardboard, tape, and string, dates variable, dimensions variable

Comments/Context: In the years since the death of Malick Sidibé in 2016, the narrative around the work of the Malian photographer has continued to coalesce and solidify, burnishing his well deserved reputation as one of the recognized masters of African studio photography.

But more practically, when an artist ages and ultimately passes away, an appropriate transition from featuring newly made work to surveying selections from the past inevitably takes place. In Sidibé’s case, this evolution can be seen in the form of a string of well edited sampler gallery shows, in 2022 (reviewed here), in 2016 (reviewed here), and going all the way back to 2011 when he was still alive (reviewed here). This new show furthers this ongoing process of synthesizing and re-presenting the artist’s singular perspective, in conjunction with the publication of a handsome new monograph.

As its title implies, Painted Frames, published in 2025 by Loose Joints (here), gathers together a group of Sidibé’s black-and-white portraits as presented in elaborately hand-painted glass frames. Toward the end of Sidibé’s life, he collaborated with local Malian artisans to craft these objects, matching his portraits (from various points in his career, some as early as the 1960s) with decorative flourishes of flowers, leaves, birds, flags, and intricate geometric patterns. Painted in vibrant colors, the embellished glass frames gave the photographs real object quality, not only amplifying the energy and grace of the portraits but providing a functional solution that was more easily presented, kept, and shared than a loose paper print.

These painted frame photo objects are sprinkled throughout this gallery show, most notably in a cloud shaped arrangement of more than thirty individual works titled the “Marriage Cluster”. An echo of the “Baby Cluster” from Sidibé’s 2011 show, the “Marriage Cluster” hits a different family milestone, bringing together posed moments of couples and extended families, most of the images decorated with painted frames worthy of the momentous occasion. Both clusters attest to Sidibé’s consistent role as a documenter of community and social events, his archive filled with the interconnections and joys of families, friends, parties, celebrations, and gatherings. The “Marriage Cluster” offers examples ranging across six decades, collapsing time into one exuberant swirl of imagery.

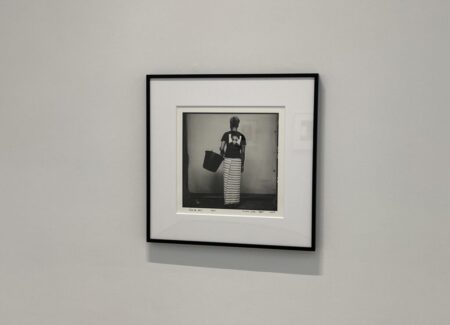

Other portraits in the show also leverage the painted frame presentation, from up close head shots to more elaborately posed and costumed setups. Whether the sitter is named or anonymous hardly seems to matter – the hand-painted decorations add energy to the proceedings, making even the simplest of photographs memorably special. This is particularly true of some of Sidibé’s portraits from the back (vues de dos), where the faces are intentionally obscured. Whether sitting or standing, hands on hips or balancing a bucket on the head, these works are more inherently formal and sculptural (since the specific identities are hidden), capturing nuances of pose against the interlocked patterns of fabrics and studio backdrops. To my eye, these from-the-back works are getting even better with the passing of time, and the ones that have the addition of painted frames (and multiple figures) are even more durably engaging.

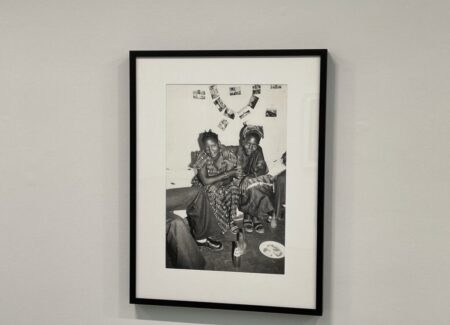

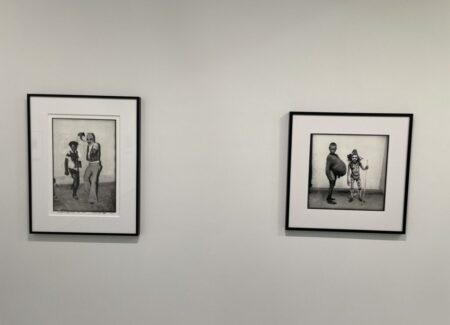

Much of the rest of the show turns back toward the vibrancy of post-independence youth culture in Mali, with Sidibé capturing the styles and looks at parties and other nightlife events. In these photographs, self-expression and personal aspiration come in many forms, from dancing and drinking soda, to posing with motorcycles or in trench coats as “faux agents”. Elaborate masks and costumes are balanced by businessmen in suits and musicians with their instruments, each image the hopeful chance to shape an identity.

In this way, the title of the show, “Regardez-moi” (“look at me” in French), has a double meaning. In one sense, it borrows from one of Sidibé’s most famous party pictures (which isn’t actually on view), capturing the voice of young man that is pulling off some crazy dance moves in the hopes of being noticed, but applying more broadly to Sidibé’s studio practice and his artistic collaboration in crafting the desired personas of his sitters. But we can also read the show’s tile as a directive to us as viewers, to look more closely at Sidibé and his art. With such authentic photographic exuberance so consistently on display, we hardly need such encouragement.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced between $8000 and $20000. Sidibé’s work is intermittently available in the secondary markets (mostly in the form of later prints), where recent prices have ranged between roughly $2000 and $48000, with a top price of $88000 for a group of prints.