JTF (just the facts): A total of 34 vintage color photographic works (9 cibachromes and 23 c-prints), matted and framed, and hung against white walls in the three north-south rooms of the gallery. One of the works, Modena, is a composite of 15 c-prints mounted on cards; the others are single prints. The works date between 1970 and 1989 and come from 12 different series—Kodachrome (17); Fotografie del periodo iniziale (1); Catalogo (1); Paessagio Italiano (3); In Scala (1); Italia Ailati (1); Il Paese del balocchi (1); Il Profilo delle nuvole (1); Colazione sull’erba (3); Topografie-Iconografie (1); Diaframme 11, 1/125 luce natural (1). Sizes vary from roughly 5×3 to 14×18 (or reverse). (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: When the 1970s color work of Luigi Ghirri first gained a large audience in the English-speaking world during the last decade, it was perhaps inevitably viewed in light of what William Eggleston had been doing at around the same time. Martin Parr and Gerry Badger, among Ghirri’s earliest supporters in this rediscovery phase, made the comparison in their entry on him for The Photobook: Volume I (2004.) Calling him “one of the pioneers of creative color post-war European photography,” they cited his 1978 book Kodachrome “as important in that context as William Eggleston’s Guide.”

As more Ghirri images from more series circulate, however, the more he appears to have been sui generis. Ghirri took many of the photographs in Kodachrome before the publication of Eggleston’s book in 1976, so it’s doubtful that the latter had a “pervasive influence” on the former, as Parr and Badger allege.

Ghirri’s delayed appreciation in the U.S.—a show at Light Gallery in 1980 was not a big hit—may have been due to the prejudice that he looked like another European Surrealist or Pop formalist. His dreamy pastels exuded a melancholic resignation before the world in which he found himself, whereas Eggleston’s descriptions of suburban sprawl in the South were so matter-of-fact as to be opaque. In zoological terms, the two artists are related in having Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans as common artistic ancestors. As fully developed sensibilities, though, Ghirri and Eggleston evolved as separate species, in environments as distinct from each other as the northern Mediterranean and the Mississippi Delta.

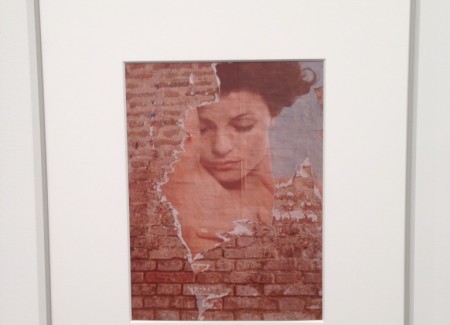

This show doesn’t so much enlarge our view of Ghirri as it does cinch the case for his excellence. Even his second-rate work—and that’s what many of these images of commercial signs, pealed posters, beach scenes, and ocean landscapes represent—has a flippant charm that’s hard to resist.

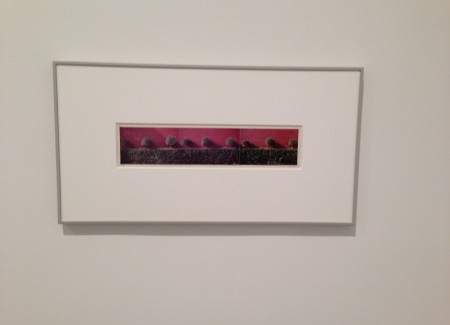

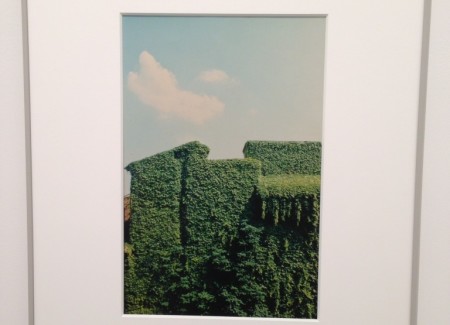

A few images here also alter the perspective of him found in Kodachrome. A grid of photographs from 1973, showing 15 almost identical views of a conical shrub in front of a house (1973) is a reminder that Ghirri was a Conceptual artist who in the 1980s adopted the serialism of Ed Ruscha and the Bechers. (The image is from the series Colazione sull’erba, the Italian translation of the Manet painting, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe. The mordant views of topiary and of industrial landscapes are like colored photographs by Hank Wessel and Lewis Baltz, two artists I had never associated with Ghirri before.)

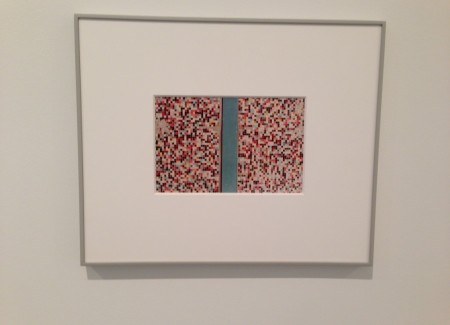

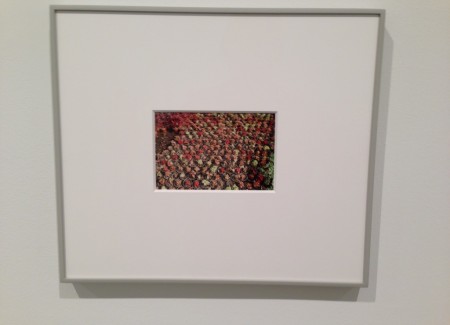

A 1971 photograph titled Modena, from the series Catalogo, is a frontal picture of multi-colored tiles that form a wall in what seems to be a public space. The wall is divided in half by a blue pilaster and the tiles on each side are dizzying, like computer lights in a vintage sci-fi film or a pixelated digital image. Ghirri did a more daring variation the next year in Modena (not featured in the show), this time creating spatial mystery by pairing a mosaic of gray tiles with a mural of a spidery bull’s eye. Where we are, and for what purpose these things exist, Ghirri refuses to indicate—or to judge.

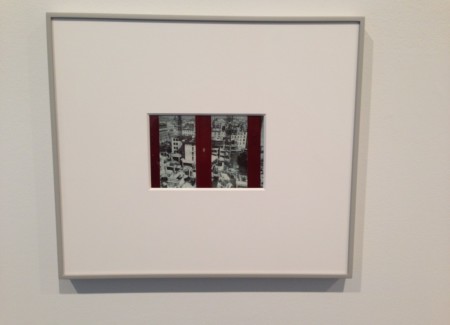

Many of his photographs seem to comment on the ambiguity of the medium itself, suspended between documenting and abstracting reality. He wants us to see the gray patches of grout around the tile. But these slapdash repairs by an unseen workman are seen within a pattern of disorientation. Like the paintings of Magritte or the films of Fellini, his images tease viewers about the nature of reality and illusion. Upside-down facades of buildings, reflected in a puddle, are cropped by the outlines of water and merge so seamlessly into the dark reddish sand that it’s hard to tell what we’re seeing. Ghirri obviously loved visual conundrums.

His color was often gentle and low-key, more like Saul Leiter’s than Eggleston’s in these years. (Oddly, Eggleston’s color since 2000 has softened, as if he had been modeling it on Ghirri’s.) The appeal of anything from the ‘70s—and the widespread nostalgia for that decade zigzagging through American youth culture today—is partly explained by our sanitized distance from its coarse realities: we are now as far away from the Dorothy Hamill wedgecut (visible here in a collage of hairstyles posted in the window of a salon) as the generation of World War II was from the Gibson Girl. The hues and the scenes in his photographs recall less stressful times, even if they weren’t.

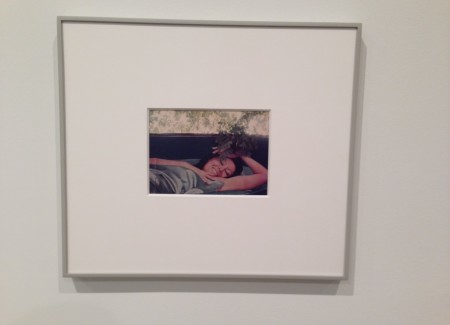

I could have done here without Ghirri’s photographs of Coca-Cola signs at the beach, lesser excerpts from Kodachrome. A 1985 view in Portugal of the blue Atlantic Ocean through a pair of sharply stepped houses—one with bleached white walls, the other in black shadow—shows Ghirri at his most conventional, following in Cartier-Bresson’s footsteps. Much more fun are the images of women from advertising or movie posters—or towels on clotheslines—who beckon to passersby with a modest downward glance or a winning smile. (One cardboard blonde in a shop window looks at us through her Canon camera, poised to take our picture with a circular flash gun.) Like most Pop artists, he exposes the corporate sham of selling products with sex while at the same time surrendering to the come-on through the act of photographing it.

By never making himself the story, Ghirri drew an attractive picture of himself. Each photograph here says as much about him as it does the time and place it was taken. Strolling around Italy without a plan, free any day to visit a park at the Colosseum or the changing rooms on Adriatic beaches, he was content to sum up a scene quickly and, if intrigued, to click a few discreet frames. He doesn’t seem to have intruded on the lives of strangers, perhaps because he found the bizarre artifacts of civilization a more enticing subject than people themselves.

If you aren’t smiling as you walk through this show, recognizing how often Ghirri must have smiled to himself as he went quietly about his business, then you have my sympathies.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced between €10000 and €15000. Ghirri’s prints have only been sporadically available in the secondary markets in recent years, with prices ranging from roughly $1000 to $55000.

Very good review. I really like his work, which sometimes verges on what in South America we call “Photoclubism”, or a heavy (and potentially tacky) tendency toward visual conundrums, rookie territory. I have always thought he played with fire, photographically speaking, skirting disaster, but managing to come out unscathed. A quote by Robert Adams comes to mind. Speaking of urban pictures in general, he said: “For a shot to be good -suggestive of more than just what it is- it has to come perilously near being bad, just a view of stuff.” Ghirri’s conundrums are witty, informed, clever, suggestive, and of course they are subtly covered by the unavoidable patina provided by time.

I haven’t seen this show in person, but happened to be in New York in 2013 when they showed Kodachrome. And for some reason I much more enjoy his work in books than in walls.