JTF (just the facts): A total of 23 color photographs, framed in walnut and unmatted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space, the smaller back gallery, and in the front window facing the street. All of the works are pigment prints, made in 2021, 2022, or 2023. Physical sizes are roughly 23×18, 30×24, or 44×34 inches (or the reverse), and all of the prints are available in editions of 8. (Installation shots below.)

A monograph of this body of work has recently been published by Nazraeli Press (here). Hardcover, 9 x 11.5 inches, 144 pages, with 71 four-color plates. Includes essays in English/French/Arabic by Willemijn van der Zwaan and the scientists of the Worldwide Painted Lady Migration Project. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: If you come to visit our home, what you’d first see these days as you approach the house is that we’ve let a large part of our previously manicured lawn go, returning it to unmowed meadow filled with an increasingly diverse set of native plants. From a climate change perspective, it seemed to us increasingly ridiculous to keep relentlessly mowing our large area of grass every single week throughout the spring, summer, and early fall, and so we’ve essentially given much of it back to nature, allowing the nearby woods and marsh to slowly reclaim some of the area. I saw a young fox out there hunting for food recently, which tells me that at least some of the local animals are happy that there’s now more unkempt habitat around for foraging.

Another logic for letting the grass grow out was to help create the beginnings of a “pollinator pathway” in our surrounding neighborhood, which is essentially a natural route from house to house that birds and insects can follow as they migrate. As the warming climate shifts where and when wildflowers and other native plants grow and bloom, these migrating pollinators have become increasingly reliant on parks, farms, and areas like our very modest (and not entirely beautiful) meadow to safely make the crossing. Of course, we rely on them to pollinate the plants and flowers in our gardens, so in a sense, it feels like a fair bargain to make the meadow available to them as a stepping stone to wherever they’re headed.

Our tiny effort to assist in this much larger cyclical migration was in the back of my mind as I wandered through Lucas Foglia’s recent gallery show. Titled “Constant Bloom”, the project is a multi-year effort (supported by a 2024 Guggenheim fellowship) to track the longest butterfly migration ever discovered, that of the Painted Lady butterfly, which makes its way from the grasslands of Africa all the way to Scandinavia. Traveling such an extended distance isn’t possible for a single butterfly, but the instinct to move is strong, and so individuals travel a few thousand kilometers each before laying eggs and passing the genetic baton to the next generation; according to the scientists Foglia was working with, it might take as many as ten generations of butterflies to make the entire journey end to end.

It’s been a handful of years since I last engaged with Foglia’s work, but it’s clear that over the past decade, the scope of his photographic ambition has continued to grow. His 2014 project/book “Front Country” (reviewed here) examined the rhythms of the American West, which he then followed up with his 2018 project/book “Human Nature” (reviewed here) which took a wide ranging look at the surfaces and effects of climate change. In a sense, “Constant Bloom” is deliberately both narrower and more expansive – it takes a single climate change-impacted subject (the migration of the butterflies) and digs in much more deeply, not only documenting its geographic extremes from continent to continent, but using the butterflies’ movement as a larger metaphor for the widespread human migration (some of it driven by climate change) that is happening all around us.

Working in color, Foglia has developed a photographic eye that centers in on everyday wonder and grandeur, wherever it may be found. This characterization isn’t meant as a kind of a backhanded compliment, but instead as an appreciation for the way Foglia pays authentic attention – he’s on the lookout for moments that quietly transcend the usual, and as a result, he captures more than his fair share. There’s a consistent warmth and humanity to his gaze that steps back from the overly easy irony of our typical contemporary wariness, the strongest of his images offering a kind of compassionate openness that encourages us to see (and feel) understated awe once again.

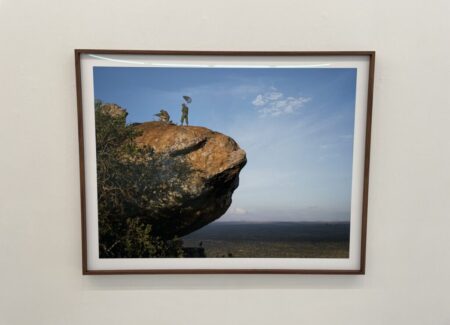

Foglia’s journey tracking the butterflies begins back in 2021 in Kenya, where he offers us an image of a Painted Lady chrysalis hanging from the thorny branches of an acacia tree. Given its fixed position, it was relatively easy to photograph, but the elusive mobility of the butterflies soon becomes a very real problem. How can an artist ever hope to capture “portraits” of butterflies, or landscapes that contain butterflies, as they flutter by on such an extensive journey? It sounds like an impossible or at least maddening task, inevitably filled with “almost” images where the butterflies weren’t entirely cooperative. So when Foglia shows us a butterfly posed on a blooming thistle (in Kenya), hidden in a sun bleached camel skull (in Jordan), perched on a swaying stem of lavender (in France), or nestled in among a thicket of wildflowers (in Spain), it seems we should do more to savor these moments of relative stillness.

Foglia wasn’t of course entirely out there on his own hoping to catch a glimpse of intermittently passing insects. Collaborating with scientists tracking the migrations in various countries, he was able to increase his odds quite a bit. Several images document these researchers at work, armed with butterfly nets and waiting patiently like hunters on the prowl. And the handful of images that Foglia did make of single butterfly specimens in flight, set against grand landscapes (the sand dunes of Morocco, a beach in Tunisia, and the cloudy sky near a glacier in Switzerland), were made with the help of those same researchers releasing the insects they had captured while gathering important scientific data. These pictures are the most dramatic, and one might say stubbornly optimistic, in the show, mostly because of the immense contrasts in scale they show us – single fragile and obviously vulnerable butterflies making an unlikely journey across vast spaces, their success seeming altogether implausible given the extreme conditions. And yet they fly on, which seems gloriously reckless and impossible.

It is this single minded persistence and resilience which is in many ways the central subject of this project. The butterflies offer one resonant symbol, but Foglia then bridges out to human (and animal) examples of this same spirit, as seen in the movements of other kinds of migrants and refugees. With the plucky narrative of the butterflies as a kind of underlying framework for the larger process of making a dangerous journey of survival and adaptation, Foglia finds plenty of repetitions and patterns to reinforce the commonality (or universality) of the instinct.

As with the butterflies, the trials for human migrants come in many forms: the expanse of the Mediterranean Sea in Tunisia dwarfing a merchant ship, the crashing waves making it difficult for a boat to row to shore in Ivory Coast, and a long walk to safety in the form of a path through ancient Roman ruins in Jordan. A more literal brush with death is seen in the stacked caskets of migrants drowned while crossing to Italy, but like the image of a fallen butterfly wing paired with a caterpillar, there is the overriding hope that the sacrifice was worth it and the next generation got further. Foglia’s images of mixed crowds in Germany seem to attest to this migratory success, and tender images of families and children in Italy and Norway offer similar hope that the next generation will change its behavior and care for this earth and its cycles with even more determined spirit.

So in the end, this is a photographic story about a shared route from South to North, about seeking new life far from home, and about the delicacy and vulnerability of this process of movement. Given the interconnectedness of the narrative arc Foglia is trying to build, “Constant Bloom” may well function more fully in photobook form than as a gallery show, if only because more images and context can be presented and interwoven. From my vantage point, I expect history will prove Foglia right about the power and pervasiveness of this broadly layered migration theme, which will continue to entangle the accumulating struggles of global climate migration with the unmown meadow in my front yard.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced at $3500, $5000, or $7000, based on size (unframed). Foglia’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.