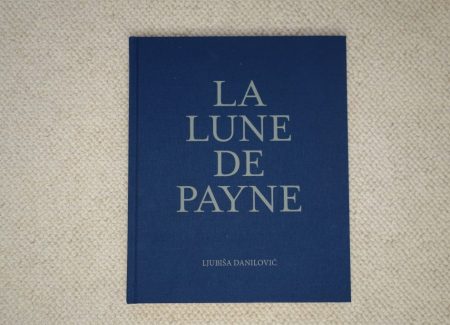

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2018 by (here). Hardcover, 100 pages, with 50 black and white reproductions. Includes a letter by the artist. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Emptiness and absence are challenging subjects for a photographer to handle effectively. As logic would imply, it’s inherently difficult to make a picture of something that isn’t present, and this lack of a primary subject forces photographers to consider the subtle nuances of what is left behind, in search of ways to visually communicate what has gone missing. Oftentimes, a photograph of emptiness is actually full of information, it’s simply the backdrop suddenly pushed forward to take center stage.

Ljubiša Danilović’s recent photobook La Lune de Payne takes as its subject life in the Danube Delta, near the fishing port town of Sulina on the Black Sea, on the very eastern edge of Romania. Once a strategic geographic entry point, it is now a sleepy backwater, where many of the people have long ago moved away, leaving the landscape to return to its natural rhythms. His pictures patiently tell the story of this creeping abandonment, their mood tracking the understated undulations of loss. And by sensitively looking closely at what remains, he has made an indirect portrait of the tranquility and mournfulness that now inhabit this place.

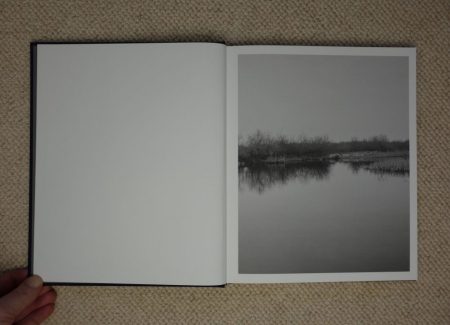

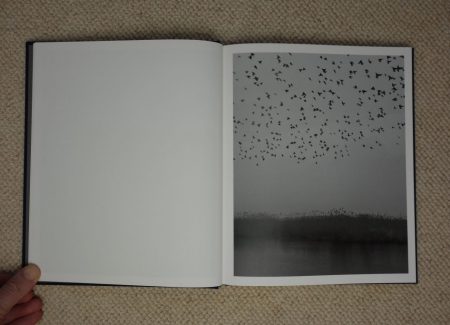

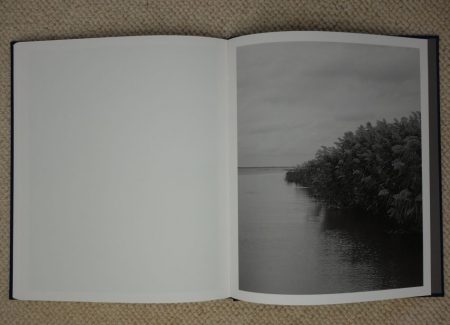

La Lune de Payne opens with a landscape image that, at first glance, seems empty. It’s the kind of forgettable non-place that Robert Adams has made famous – some low scrub trees in winter, some spiky water grass, an expanse of middle grey sky, and the softness of flat water. In his eloquent introductory letter, Danilović describes this muddled expansiveness as “in the delta, sky and water swallow everything up,” and subsequent landscapes fill out this description with more examples of gentle openness. You can almost hear the urgent rustling of wings as a flock of birds rises from the marshland, or the tiny quiver of the water as it passes upriver. The views are wide, the tones are muted, and the distinctive landmarks are nonexistent, the land reduced to unperturbed serenity.

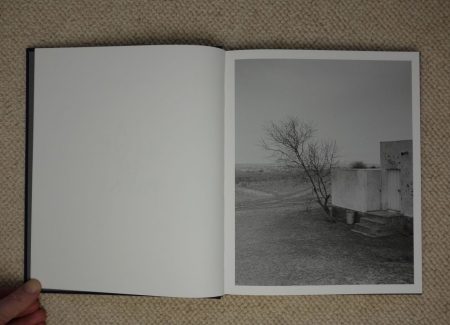

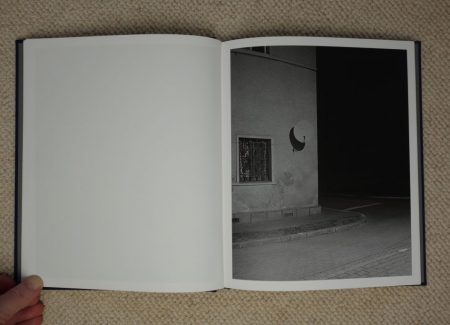

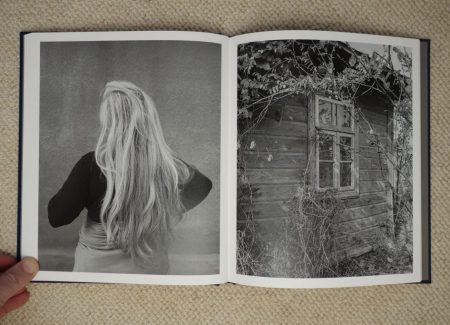

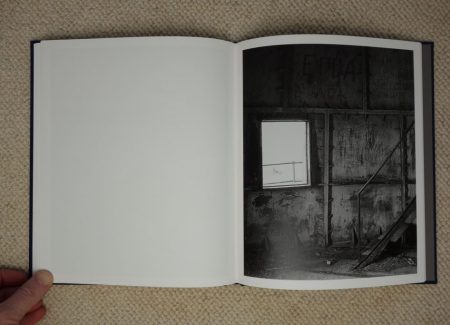

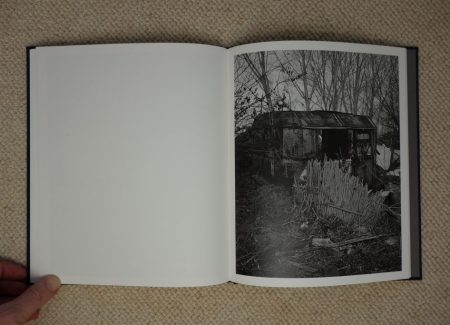

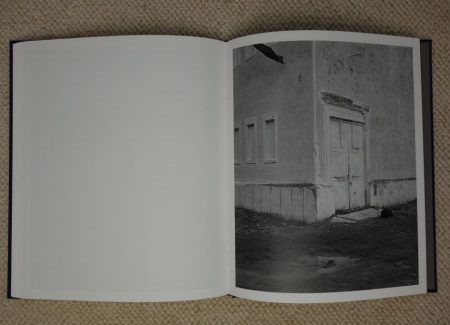

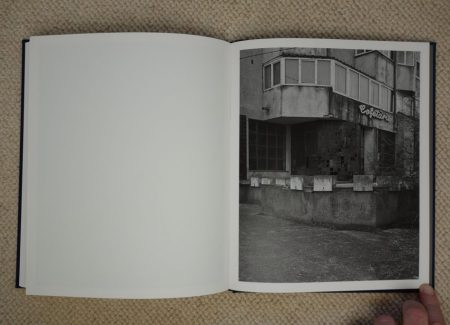

As Danilović slowly moves us through the landscape, signs of life appear, mostly in the form of decaying built structures. The images encourage the hard edges of geometry to fall into mottled middle hues, where concrete crumbles, paint peels off walls, wood planks weather and rot, and nature begins its process of reclamation. In many ways, surfaces and textures become the subject of interest, with muddy roads, graffiti covered walls, and encroaching vines telling the story of quiet desolation.

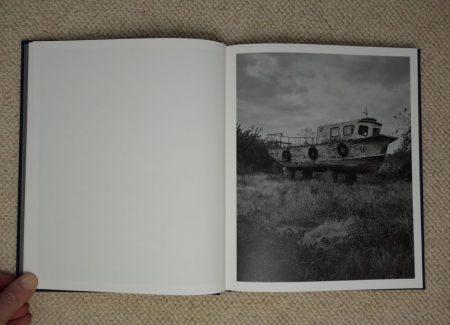

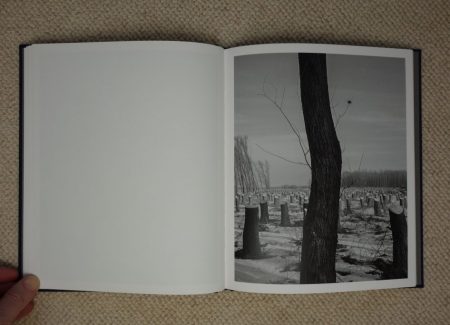

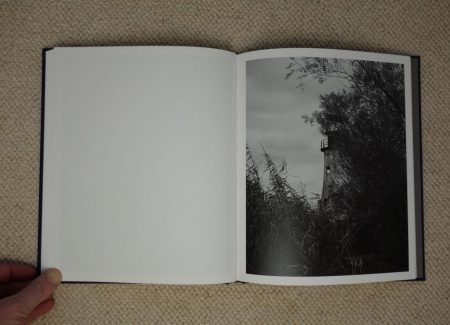

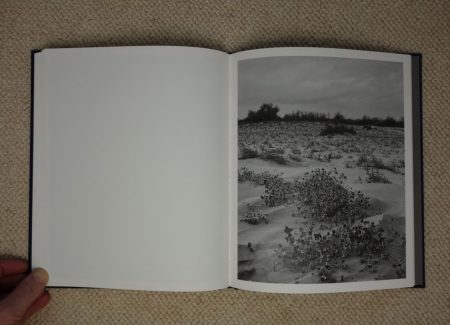

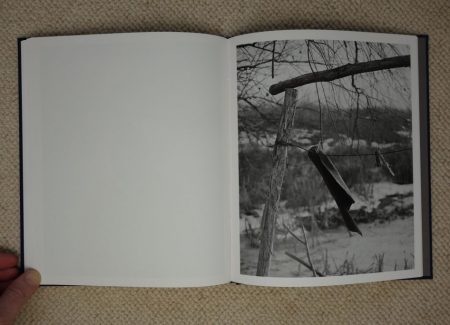

Loneliness simmers through Danilović’s photographs, sometimes portrayed a sense of lost purpose. Single birds sit on wires or float through the air, separated from the flock. A rotting boat sits atop oil drums in the tall grass, far from its natural place on the water, and a rag flutters on a makeshift wire clothesline. A triangular sign sits like a broken skeleton near the beach, where the sand is slowly being covered by spreading plants and a lighthouse is becoming lost in taller growth. Perhaps the grimmest image shows us a single tree trunk against the grey sky, the land behind it clear cut, leaving the shorn trunks like acres of tombstones. The cemetery motif (and the death it represents) then continues with an image of an actual gravestone statue pockmarked by the unforgiving weather.

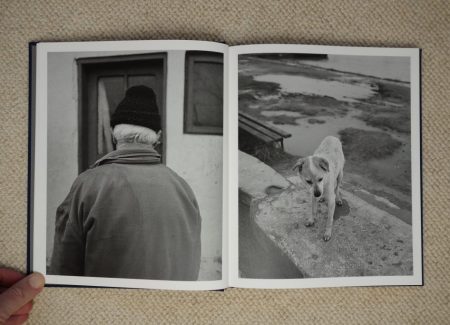

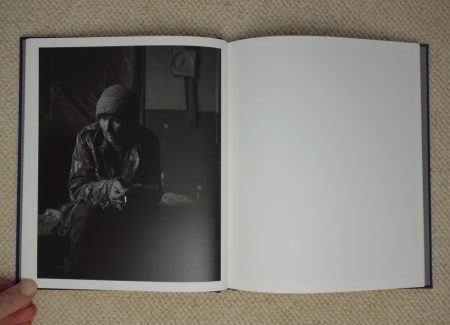

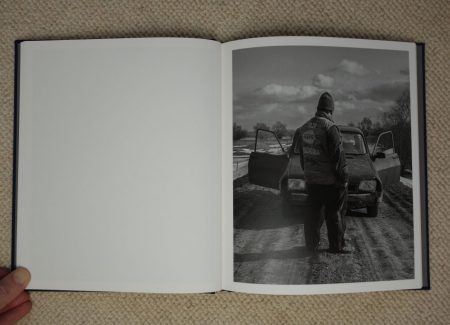

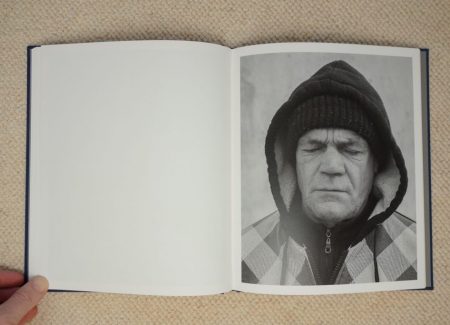

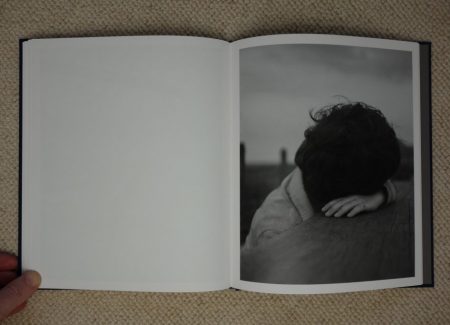

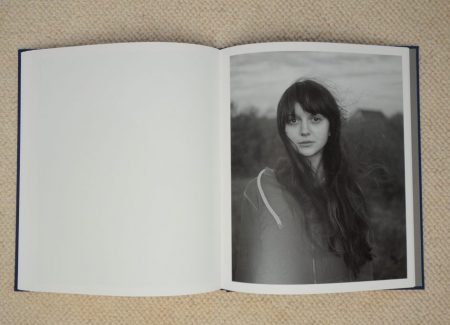

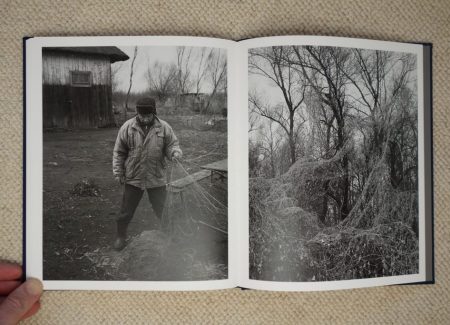

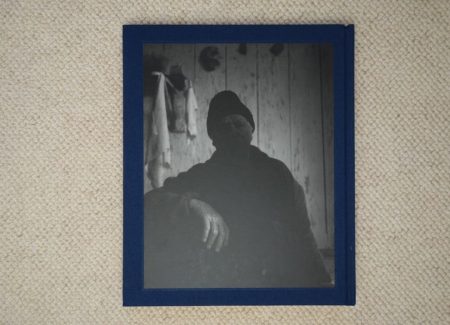

Danilović’s portraits of the remaining inhabitants are universally empathetic and often beautiful, but they largely avoid direct exchange. Aside from the penetrating stare of a young woman with windswept hair and one or two other images, his subjects are alternately seen from the back, with heads turned, mostly looking away (sideways, down, or skyward), sometimes almost entirely lost in shadow. These are pictures that capture the tenor of humble perseverance, and resignation, and solitary despair. An older man despondently examines his fishing nets, seemingly acknowledging that the life they represent is disappearing; another simply closes his eyes, perhaps in weariness, or in avoidance of hard truths. Even a small dog looks forlorn, standing amid the muddy puddles; the horse behind a weathered wooden fence in another image looks no happier. Collectively, they are the survivors, which may be no prize worth winning.

In terms of construction and design, La Lune de Payne is a “traditional” photobook, in the best sense of that description. All of the images are vertically oriented, making the organization of the book straightforward – images alternate on one side of the spread or the other, with a few double spreads thrown into break up the flow. The reproductions are well executed, with a lyrical attention to tonal gradation, the grey almost “blue-tinged”. There is enough white space to control the pacing, and the images are large enough to engage with fully. The text is sparse but informative. The book is everything it needs to be and nothing more, encouraging the viewer to be swept into the photographs.

In the end, these images of the Danube Delta feel silently haunted, not by ghosts or ghouls, but by the enduring presence of the past. Danilović delivers a melancholy meditation on the downward slide of the life cycle in La Lune de Payne – man reluctantly gives up on his attempts to be master and nature slowly takes back and renews what has been returned to its charge. What he’s captured is the invisible emptiness that now inhabits this land, and the acceptance of that absence by those few that have chosen to remain. Frustration and futility have been ground down, leaving behind a lingering ache.

Collector’s POV: Ljubiša Danilović does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As such, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar) or with Tendance Floue (a collective of which he is a member, here).