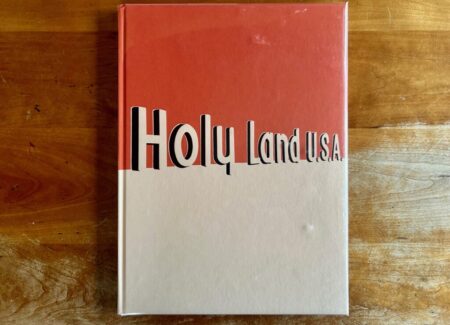

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by Stanley/Barker (here). Foilstamped hardcover, 330 x 245 mm, 104 pages, with 53 monochrome photographs. Includes an essay by Brad Zellar. Design by Bill Sullivan U.S.A. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Stanley/Barker is run by the husband and wife team of Gregory and Rachel Barker. Their London-based imprint is a relatively new kid on the publishing block, just ten years old as of this month. But their back catalog is wise beyond its years. Most monographs to date have resuscitated photography projects from the black-and-white film heyday of the 1970s and 1980s. Many are sourced across the pond in the United States, with women photographers particularly well represented. American basements and closets are rife with strong pictures, but the trail is sometimes faint. Despite best intentions, many archives fade toward obscurity over time, scattered to the whims of storage, chance discovery, and curatorial moods.

But overlooked does not mean unworthy of a look, and in the forgotten cracks of history Stanley/Barker has struck paydirt time and again. With many hits and few misses, they’ve established a solid track record identifying and producing neglected projects into books. And in so doing they’ve created and filled a key niche in the photo ecosystem, the publishing equivalent of mycrorhizae or lobsters salvaging nutrients to regenerate the life cycle. Photographers such as Sergio Purtell, Jack Leuders-Booth, Karen Knorr, Judith Black, Joan Albert, and Susan Kandel have enjoyed minor career bumps in recent years, largely thanks to Stanley/Barker’s publications.

Stanley/Barker’s latest revelation is Lisa Barlow. Until encountering her debut photobook Holy Land U.S.A. I knew nothing of her work. Just a few pages into the series were enough to trigger my curiosity. Who is this person and why was I not aware of these photos? “I am a Brooklyn, Colorado and Mexico City based photographer,” she describes herself on her website. “My long career includes many years as a documentarian for Public Television, a teacher at three NYC private schools and a writer for the International Center of Photography.” That’s her now. Back in 1980, she was an undergrad at Yale when she first stumbled upon Holy Land U.S.A., a Catholic theme park built by John Baptist Greco in nearby Waterbury.

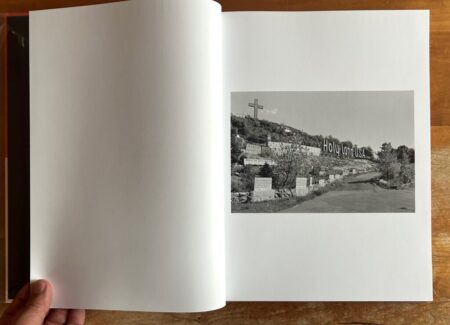

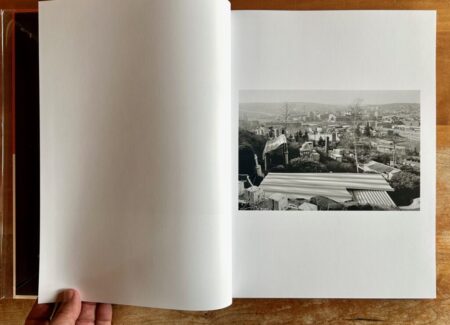

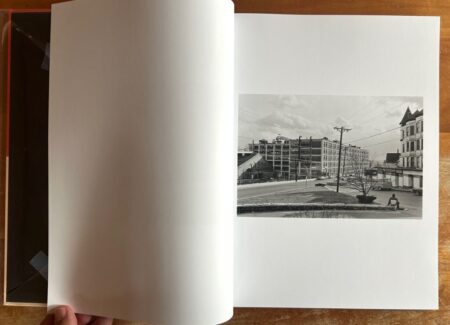

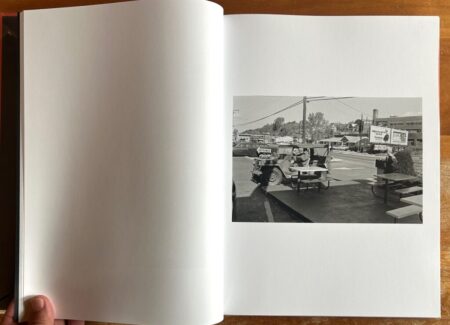

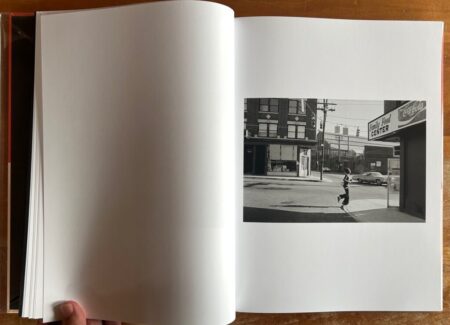

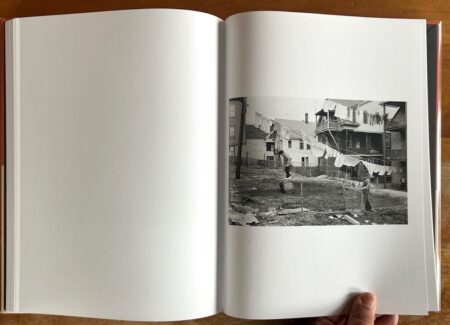

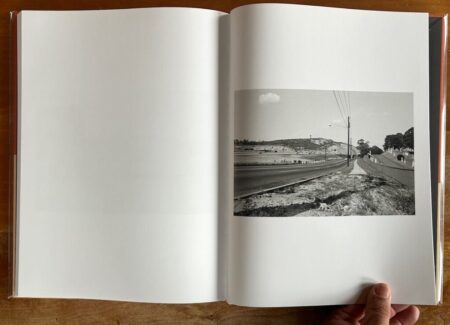

To learn what happened next, we turn to the book. Holy Land U.S.A. is loosely sequenced as Barlow’s path of discovery. It opens with a handful of photos establishing Holy Land’s setting on a high bluff. It’s the sermon on the mount, in theme park form. Statues of Christ on the cross, scripture on stone tablets, and rocky pedestals carry a Biblical mood. They feel pious and devotional, even if slightly corny. In any case overt religious imagery proves to be a red herring, as Barlow moves downhill to unveil her real photographic interest: the post-industrial fabric of Waterbury, sprawling below in the bottomlands. Here she stays for the remainder of the book, documenting local establishments, street corners, kids at play, back yards, and the city’s social landscape.

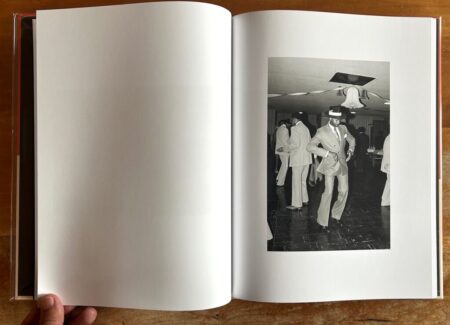

Stylewise, Barlow’s photos slot into the small format black-and-white school of serendipity which was relatively common circa 1980. “She flits through,” writes Brad Zeller in the afterword, “like a humanistic wraith armed with nothing but her camera and a bag of fairy dust.” This phrase might also describe Stanley/Barker cohorts Paul McDonough and Sage Sohier, working in the same regional era. All three photographers specialized in a type of hamlet flâneurship applying urban street photography modes to Main Street America. It’s worth noting that all three studied at various times with Tod Papageorge (another Stanley/Barker stablemate). His fairy dust is sprinkled across the generation, along with the ghost of his mentor Garry Winogrand. If they espoused any central premise, it was that good photographs might be taken anywhere, at any time or situation. In Holy Land terms, any water could be made into wine. Redemption could happen at any moment. It was up to the photographer.

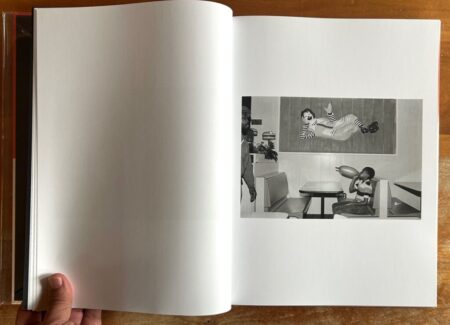

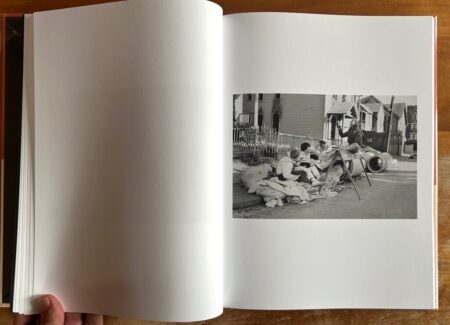

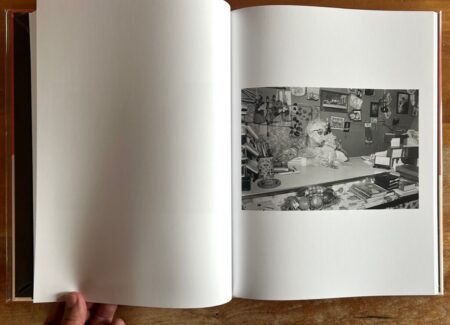

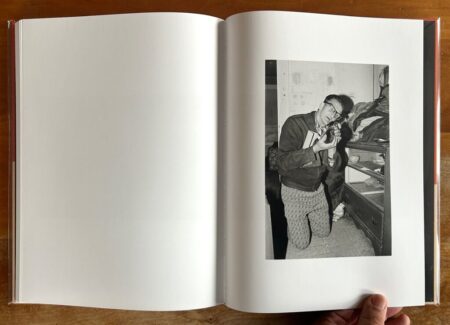

Barlow applied this approach with relish to Waterbury. Judging by her pictures, she made pilgrimages to all parts of the city, salvaging miracles regularly from ordinary situations. A scene of kids roughhousing near a storefront, for example, might degenerate into a chaotic mess if shot a second earlier or later. But her quick eye crystalized limbs and heads into a perfect clump, juxtaposed with a sharp-dressed boy nearby. An interior shot at McDonald’s snatches a gem from happenstance with similar aplomb. A boy’s balloon, Ronald McDonald, and passing customer are frozen in holy trinity.

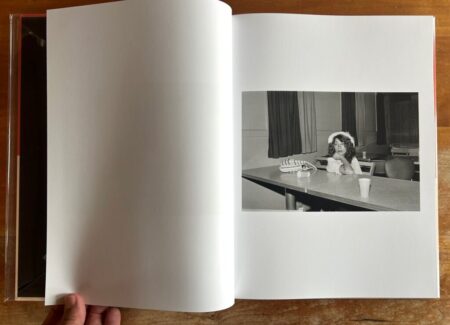

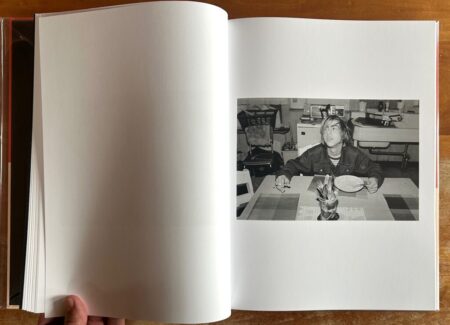

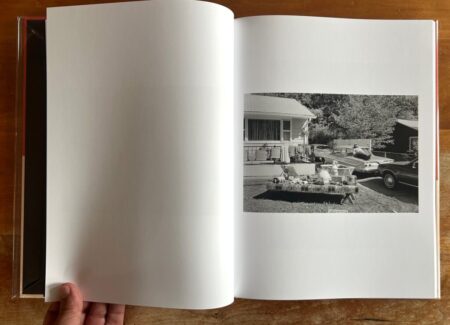

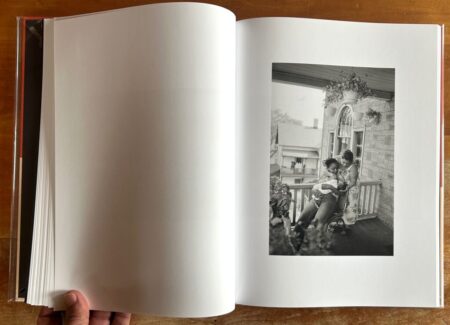

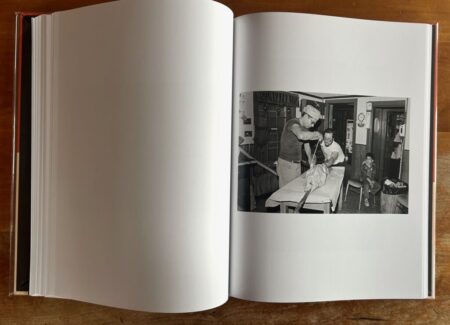

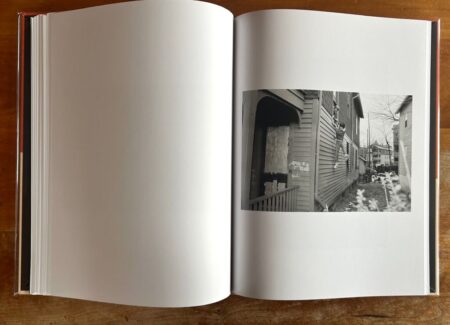

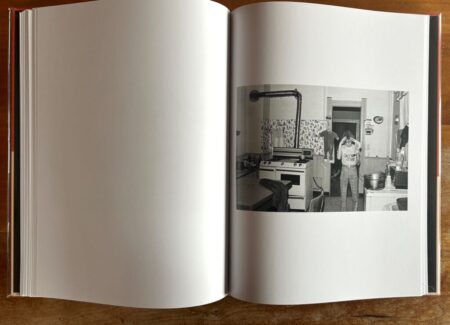

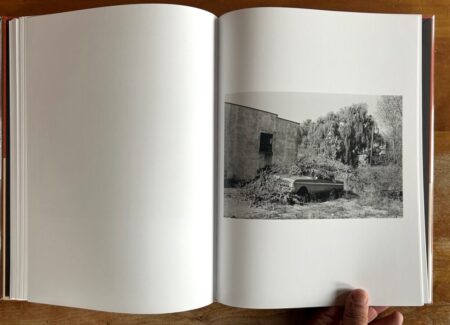

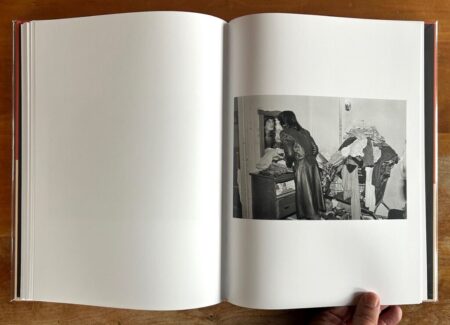

Many photos document ventures into domestic interiors. The circumstances aren’t clear. Perhaps Barlow was asked to join? Or she invited herself along with acquaintances or friends? However she gained access, she made good use of the opportunities. A photo of a teen laying below a wall of snapshots is deftly seen and composed, with a whiff of smoke as the visual cherry on top. Several photos show families in the kitchen or dining room, prepping for meals or gatherings. Barlow’s flash adds monochrome contours, with shadows, appliances, and furniture in tight balance. A small handful of photos in the book contain no people at all. But these views into overgrown lots and autos add social texture. If the top of the hill was reserved for Holy Land exaltation, it seems bottom dwellers were left to their own devices.

As it turned out, Barlow photographed Waterbury in the twilight of Holy Land. The site went belly up in 1984, a few years after her visits. It was the end of an era, but all was not lost. After a thirty-year hiatus with its structures falling into disrepair, a fresh-faced Holy Land reopened to the public in 2014. Perhaps theme parks are like certain photo careers or messianic figures? A period of dormancy can sometimes lead to salvation and rediscovery.

In Barlow’s case, the rebirth was shepherded by the ultimate deep freeze, the 2020 pandemic. When society shut down, she used the time to dig into old photo archives. A few years later she presented them at Chico Review, where they were spotted by Brad Zellar, and eventually—a Hallelujah moment—Stanley/Barker. In Holy Land terms, you might say her project was Saved! Reborn! But one needn’t appeal to liturgical explanations. Barlow’s photos prove that everyday life is its own quiet miracle.

Collector’s POV: Lisa Barlow does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up with the artist directly via her website (linked in the sidebar).