JTF (just the facts): A total of 39 black and white photographs, framed in white/black and matted/unmatted, and hung against cream colored walls in the main gallery space, the smaller side room, and the entry area. 26 of the works are gelatin silver prints, including 3 contact sheets, made between 1947 and 2004, with many of the older images reinterpreted/reprinted in 1994. Physical sizes range from roughly 9×7 to 40×30 (or reverse), and editions sizes run from unique to as many as 25. 9 of the works are platinum prints, made between 1950 and 1996, with some once again reinterpreted in 1994. The platinum prints are generally sized 30×24 (or reverse) and are available in editions of 15. The final 4 works are archival pigment prints, made between 1950 and 1960, and reinterpreted in 1994. These prints are sized between 40×24 and 58×42 are available in editions of 12. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Edwynn Houk has recently taken over the representation of the estate of Lillian Bassman, and this survey show provides a succinct first level introduction to her career in fashion photography. Bassman’s story is really an aesthetic before and after tale, with two distinct sections to her artistic output. And while the exhibit doesn’t make this evolutionary two-step particularly distinct, it’s worth looking for, if only to recognize how revolutionary her later work became.

The backstory to Bassman’s art goes something like this. In the first phase, she trained under Alexey Brodovitch, ultimately working as an art director and photographer, with her images routinely appearing in Harper’s Bazaar from the late 1940s to the early 1960s. Her early works from this period are traditionally crisp and meticulously staged, but over the subsequent years, she introduced various softening techniques in the darkroom, smoothing out the lines and increasing the contrast via various bleaching and toning techniques. But by the early 1970s, she had had enough of the commercial fashion world, so she left the industry and destroyed most of her negatives and prints. The second phase of her career began some twenty years later in the mid 1990s, when a box of old negatives was rediscovered and she began to reinterpret them. With an increased sense of freedom, she took her impressionistic manipulations further, transitioning to digital effects as the technology changed. At the end of her life, the unique innovations in her work were finally being recognized.

There is really only one true before and after pairing in this show that examines the specifics of Bassman’s evolving style, and it is unfortunately spread across the doorway in the side room. In an image from 1951, we see the elegant Dovima in the Plaza Hotel, seated in a ruffled white dress (by Jane Derby), with a candelabra and tuxedoed waiters in the shadowy background. The early iteration (on the left of the doorway) is quite dress-centric – its layers of delicate ruffles are seen with exacting detail, its contours and flow spilling to cover the lower half of the frame. Lovely pure light pours in from the right side, highlighting the side of Dovima’s face and torso, and pushing the rest of the scene into darkness, drawing our attention to the intricacies of the dress.

The later iteration (to the right of the doorway) turns the exact same scene into something entirely different. The dress is now largely bleached out to a wash of intense white, its lacy detail made secondary. Dovima’s pose and facial expression are now front and center, the curve of her shoulders and the turn of her head the focal points of the image – what interests us is how she carries herself, and the confidence of her implied attitude. The entire scene has been made more contrasty, the darkness of the background lightened to reveal the shape of the candelabra and the ghostly forms of the waiters shifting in and out. What was once a quiet and serene set piece is now filled with implied motion, with watercolor-like washes of black and white drifting through the blurred action.

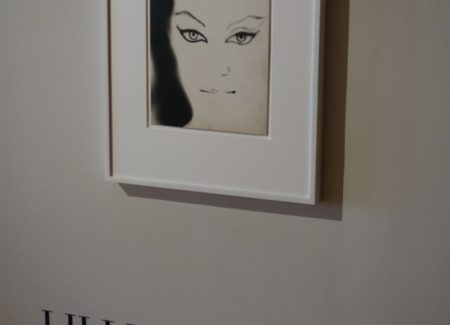

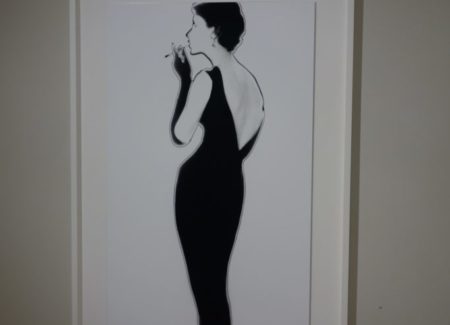

In many ways, the rest of the show is just an amplification of what can be found in these two pictures. Early works, including a series of contact sheets, highlight gorgeous folds of fabric, graceful bare shoulders, and specific garment details within the context of 1950s era stereotypical femininity. And the later works transform these same images into exercises in sinuous line and form, streamlining and reducing the information provided, allowing bright contrasts, bold lines, and gauzy indistinctness to dominate the compositions. In some cases, Bassman took her manipulations to surprising extremes, where bodies became enveloping black silhouettes and edges are turned into the equivalent of gestural ink drawings – a veil looks like a swarm of black dots, a neckline bow becomes a slashing X, the strap of a stiletto jumps out from a flat white leg, and the buttons of a coat settle like dripped spots. This process served to highlight the elemental formal qualities of female bodies and the architecture of well-made garments, turning the images into fleeting dreamlike impressions of a universal modern woman rather than advertisements for actual dresses – a the years passed, she was increasingly after a fundamental idea of womanhood not the thing on the surface.

This wholesale redefinition of glamour (and the expansion of the acceptable visual vocabulary used to capture the genre) is Bassman’s enduring contribution to the history of fashion photography. In her reinterpreted works, she replaced old school femininity with something more confident and artistically self-assured, where the singular impression of a dangling necklace, an asymmetrical hemline, or the jaunty tilt of a hat gave us a squint-eyed glimpse of the subtle essence of grace.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced between $11000 and $40000, to some extent based on size. Bassman’s prints have become more consistently available in the secondary markets in recent years, with prices ranging between roughly $4000 and $50000.