JTF (just the facts): A total of 16 color photographs, framed in welded steel and matted, and hung against cream-colored walls in the main gallery space. All of the works are inkjet pigmented prints, made in 2023. Each image is sized roughly 12×17 or 14×14 inches, and is available in an edition of 5+2AP. The show also includes 1 box of 12 color slides and manual viewer, 2023, each slide sized roughly 2×2 inches, in an edition of 15+2AP, and 1 color video, 2 minutes 50 seconds. (Installation shots and video stills below.)

A monograph of this body of work was published in 2023 by Editions Textual (here). Hardcover with tipped in cover photograph, 29 x 27 cm, 104 pages, with 55 color photographs. Includes an essay by Taous Dahmani, and a conversation between Lee Shulman & Omar Victor Diop, recorded by Marianne Théry and Manon Lenoir. Texts in French/English. Design by Agnès Dahan Studio. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: Given the increasing appreciation for vernacular photography that has taken place in museums, galleries, photobooks, and really throughout the world of photography in the past decade or two, the fact that the images on view in this gallery show are presented like enlarged Kodachrome slides, with hard metallic edges and mats with rounded corners, isn’t entirely unusual. Of late, we’ve slowly been retrained to see the artistic value and historical importance in previously overlooked snapshots, and plenty of worthy bodies of vernacular work have been rediscovered and recontextualized in respected venues around the world, ensuring that we no longer immediately underestimate the power of the humble color slide.

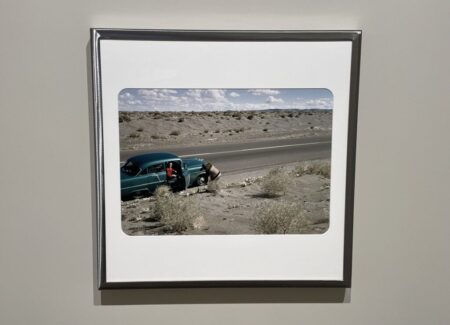

The framing approach used for the works by Lee Shulman and Omar Victor Diop in their project “Being There” is by no means accidental or random – the familiar styling clearly evokes a kind of nostalgia for the culture of the slide era, particularly as seen in 1950s white middle class America. And a quick glance around the room from afar might yield the conclusion that these images are just what they seem to be – informal snapshots of the lives of such people in such times, capturing on film the everyday visual rhythms and domestic social rituals of holidays, birthdays, tourist trips, new cars, family gatherings, dinner parties, and other modest milestones documented by any number of now anonymous amateur shutterbugs. Except for one unexpected detail – in each image, there is a black man casually included in this otherwise entirely white world, and given the racially segregated and pre-Civil Rights moment in American history from which these images are drawn, his unassuming presence is altogether surprising.

My colleague Blake Andrews has already thoroughly unpacked the “Being There” project, as seen in photobook form in 2023 (reviewed here), so I won’t recross all the ground he has already ably traversed. Head back to his insightful analysis to consider who Lee Shulman and Omar Victor Diop are, why they embarked on this project together, where the original vernacular pictures came from, what their respective roles were, and how they did with they did. The backstory to this smart project is certainly worth knowing in detail, if only to amplify how impressive the end results are. And while we normally wouldn’t double up and reconsider the gallery show of a photobook we have already reviewed, this project is an undeniable standout that deserves a second look.

One of the things I find fascinating about the pictures in “Being There” is how they so eloquently use understated humor as a wedge into a much more charged set of racial ideas and realities. For many white viewers, the initial response to these images might be a chuckle at how odd it is to see a black man in these dated scenes. And the images are indeed consistently funny, the way that old snapshots can be – Diop is caught behind some balloons at a birthday party, stands proudly with his snow shovel, enjoys a glass of wine wearing sunglasses at a seaside bar, arrives smiling with a case of beers, whacks golf balls in his suit pants, compares vinyl records with a friend, and deals with a flat tire while his wife waits in the car. The scenes are altogether ordinary and Diop has an easy going charm and charisma that feels completely natural – he belongs in these moments, except of course that he doesn’t, which is where the comedy turns darker, to something much more uncomfortable.

It is this racial tension that so incisively pokes out from each and every image in this series, refusing to go away. While it should have been entirely unremarkable for Diop to walk to his car in front of his suburban home with its blooming lilac bush, or to mug for the camera in a tuxedo at a convivial Christmas party filled with streamers and paper hats, or to sit at a dinner party with friends with the same white shirt and suspenders look as the other (white) man at the table, it wasn’t. The familiarity of these snapshots is an illusion, and the longer you look at the images, the more the discomfort and dread seems to build up, knowing full well that the lone black man playfully strolling through white 1950s America here is imaginary.

Beyond this fundamental conceptual conflict, a second idea worth noting is just how masterfully Shulman and Diop have executed their illusions. Back in the 1990s, at the beginning of the digital revolution in photography and video, many were amazed by the scenes in Forrest Gump where Tom Hanks is inserted into historical footage and seemingly shakes hands with JFK (among other exploits). And since that time, the technology has improved by leaps and bounds, but the storytelling conceit (at least in this project) hasn’t really changed. I’m astonished when I think about the range of technical detail and meticulousness necessary to pull off these pictures so faithfully, even when the source files start with empty chairs, open doors, and spaces where Diop’s figure could reasonably be inserted. The hurdles are so many: the period costumes, the precise alignment of expressions, looks, poses and props, the lighting (including intricate matching the angles and intensities of highlights and shadows in the original images), the color correction to the dated film stock, the exacting placement of focus and blur, and ultimately the digital insertion and stitching together. That the resulting images look as good as they do, as faithful to the aesthetics of the time as they appear, is a testament to the artists’ hard work, and in many ways, a shining example of how digital manipulation can be thoughtfully used to make innovative photographs we haven’t seen before, like a decades old promise finally cashed in.

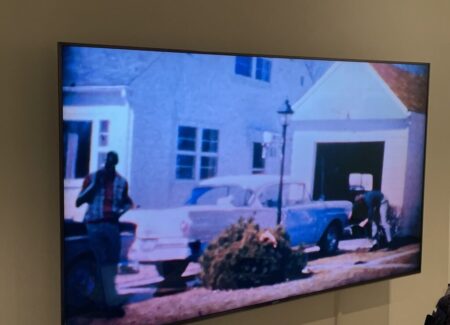

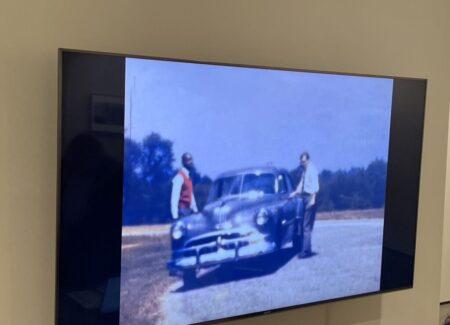

Along with the framed prints on display, this show also includes two other nostalgic form factors for Shulman and Diop’s collaborations. One comes full circle to the slide format, printing the “Being There” images on actual color slides and presenting them with a vintage-styled slide viewer. The action of pressing the slide into the plastic viewer and seeing it light up on the small screen will feel like a throwback to many (or a puzzling artifact for those somewhat younger), the entire physical process adding another layer of apparent authenticity to the artists’ recreations. The other is a short video, seemingly pieced together from short snippets of silent 16mm home movies, and employing the same effect of inserting Diop into the scenes. The technical difficulties with this magical transformation were likely even more challenging than those in the still frames, as now Diop has to move and respond to the scenarios around him. But once again, the moments are altogether real and surreal, with Diop playing croquet with girls in party dresses, feeding seagulls at the beach, helping out with a backyard barbecue, having a drink at a festive cocktail party, disembarking from a plane (when people still came down the stairs), and drying off with a towel while sitting at the beach.

At a time when words like diversity and inclusion have been overtly politicized, this project feels all the more radical in its impersonations and representations. Starting with a reality as documented by dated vernacular photographs, Shulman and Diop have crafted fictions that broadly undermine that reality, particularly as they quietly reconfigure families, friendships, and other social structures and interactions. These images are so very unstable – every one of them refuses to adhere to the expectations of white 1950s American life, with uneasy dualities of absence and then presence, or the outsider who is now an insider, constantly tugging in opposing directions. The result is a project that often feels altogether subversive, but in a way that is so clever and graceful that the critiques feel gentler than they actually are.

To my eye, Shulman and Diop’s “Being There” deserves to be placed on the shortlist of landmark contemporary photography projects of the 2020s. I’ve now seen this work presented in book form, at art fairs, and in a gallery show, and with each viewing, its contagious energies and conflicted nuances have gotten stronger. It’s a bravura photographic combination of biting intelligence and painstaking execution, and one that should be much more widely known and appreciated than it is.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show are priced $7500 or $12000, based on the place in the edition. The box of slides and viewer is also priced at $7500. Works from this collaboration have not yet consistently found their way to the secondary markets, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.