JTF (just the facts): A total of 6 large scale color photographs, framed in white and unmatted, and hung against white walls in the southeast gallery on the museum’s second floor. All of the works are pigment prints, made in 2015. Each print is sized 70×48 and no edition information was provided. (Installation and detail shots below.)

Comments/Context: The “uncanny valley,” a term that originated in Masahiro Mori’s aesthetic theory of robotics, describes a trough in the wave of emotions felt by human beings as they confront and sort out their reactions to the presence of artificial creatures.

When robots are perceived as clunky armatures of metal and plastic, we are apt to feel superior in watching their stiff attempts to move and “think” as we do. Dependent on programmers and mechanics, they’re helpless children and we’re the parents. Robby the Robot from Lost in Space is an unthreatening curiosity. His/its slavish replications of a human voice and mobility are so crude and imitative that he is essentially genderless.

Not until machines “evolve” to the extent that their facial expressions and bodily actions become more lifelike—and we are in doubt whether what we’re seeing is alive or manmade—do our emotions noticeably change. Scientists have noted that we are suddenly afraid and repulsed by robots that look and behave too much like us. That threshold, when a robot so closely resembles a human being in gesture and texture that it scares us, is the “uncanny valley.”

Finally, the theory goes, as robots become indistinguishable from humans, our emotions do another somersault and they are no longer freakish. Instead, we welcome them as equals and comforting helpmates. “David,” the character played by Haley Joel Osment in the movie A.I., is a robot child so advanced in design that it yearns to be human and is accepted by adults as such.

How We See, the 2015 series by Laurie Simmons, may provoke the same sine curve of emotions from some viewers even though she is reverse engineering the human-machine equations that operate in the uncanny valley. Her six portraits depict humans who yearn to be viewed as artificial: they are members of the “Doll Girls” community—people (mainly young women but sometimes young men) who alter their appearance with make-up and outfits and cosmetic surgery in hopes of achieving the “perfection” of a recognizable mannequin—of Barbie or a well-known anime figure.

Their motivation is akin to that of drag queens, who craft themselves to be more like movie or music stars, except that the role models for “Doll Girls” are inanimate. Both groups rely on physical transformation and trompe l’oeil deception to send an aesthetic shiver through their audience.

An artist affiliated with the Pictures Generation, Simmons has since the late ‘70s investigated the social construction of the self in a series of photographic series. The focus of her career has been remarkably tight and consistent. From Early Color Interiors (1978) and Tourism (1984) and Talking Objects (1987) to Kaleidescope House (2001) and The Love Doll (2009), she has used her camera to make theatrical studies of dolls or “dummies” or inanimate objects (furniture, clothes, accessories) that question how we act out, imagine, deflect, or speak about our desires through these surrogates or miniatures. It’s a highly directed form of photography devoted to the subject of indirection.

The young women in her How We See are engaged in what they call “cosplay”—an Asian port-manteau expression that mixes the words “costume” and “play.” Simmons sees a connection between cosplay and the rapid exchange of pictures and texts via social media—an analogy that I frankly don’t follow. They are stars of the Internet and therefore everywhere and nowhere. But the pace of and imagery on Instagram, Snapchat and Vine is ceaseless, fleeting, usually trivial, and morphologically unstable, whereas the “Doll Girls” abjure quick and slapdash reinvention. Their pursuit of an idealized self requires time and labor to costume persuasively; the photographic portraits they sit for—or commission—are anything but spontaneous; they’re supposed to demonstrate the care and thought and money needed to achieve their lacquered glamour.

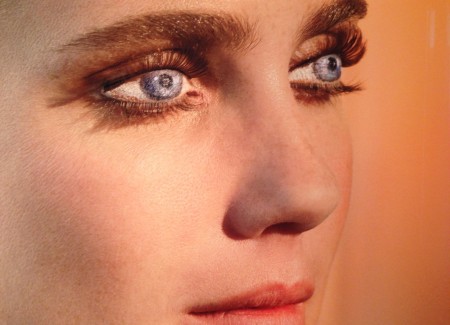

Far more unsettling than a spurious bond with the Facebook generation is the central visual paradox of these portraits: these women want so much to look like dolls that they have hired makeup artists to paint eyes on their closed eyelids.

As a result, because they have purposely “blinded” themselves, they can never know how they look except after the picture is taken. They are at the mercy of Simmons and her camera, which can offer the only evidence they will ever have to prove whether they have succeeded in looking as they hope to. They can only see themselves through photographs—a theme that snakes through Simmons’ oeuvre.

Freud’s theory of the uncanny depended on an unorthodox reading of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s The Sandman. In this story about the creation of a lifelife female automaton, Olympia, and her mad inventor Coppola/Coppelius, it is the doll’s eyes—and the loss of sight when they’re plucked out—that for Freud was the heart of the horror.

A collaborator in these portrait sessions with her living Dolls, Simmons is the opposite of judgmental or undercutting. Each person is respectfully titled by her (stage) name and by the color of the photographic background behind her: Lindsay (Gold); Ajak (Violet); Peche (Pink), etc. The lighting and flatters their make up and skin tones; and the luscious color prints are bigger than lifesize. In completing their performances, Simmons confirms their glamorous view of themselves.

At the same time, I’m guessing that only a special sort of art collector would enjoy hanging one or more of these portraits on the wall for any period of time. Their eyes don’t actually follow you, as do the ones in paintings along the corridors of haunted mansions in Scooby Doo cartoons. But their painted faces, composed of flesh as well as a harder, chillier substance, seem villainous enough that their presence lowers the temperature of the room at the Jewish Museum by several degrees.

Collector’s POV: Laurie Simmons is represented by Salon 94 in New York (here) and prints from the same series were on view at the recent Frieze New York art fair, priced at $42000 each. Simmons’ photographs have become more readily available at auction in recent years, with prices ranging between $1000 and nearly $100000.

This article and Laurie Simmons’ works share the same eccentric, quirky attitude. Your well-read writing has made more comprehensible some recent Simmons’ photographs. Since The Doll Series (2009) her work could seem cold, more abstract and distant. She has increased the cultural notions involved in her projects, giving them a specific orientation. In fact,the concept of Anime Kigurumi was since 2009 a new starting point…

Thank you